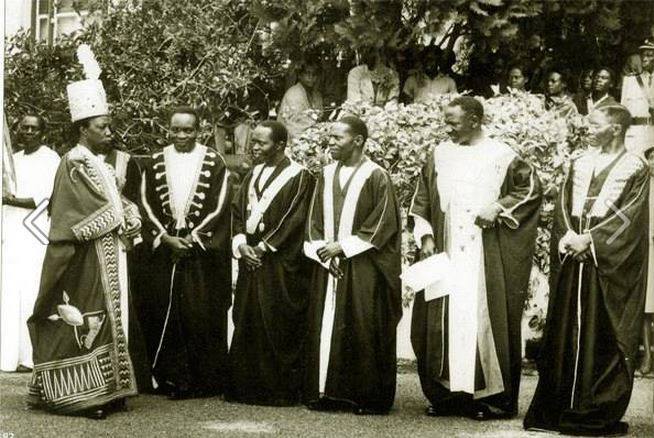

The last photograph before the Kabaka’s departure from Uganda. It was taken on his 29th birthday, November 19, 1953, outside the Kabaka’s palace, where he sits surrounded by his Ministers, and Chiefs, the Abakama of Bunyoro, Toro and Ankole, and religious and civil leaders.’

CHAPTER TWENTY

THE STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE IN UGANDA 1945-1962

Freedom is not a commodity that is given to the

enslaved upon demand; it is the precious reward, the shining trophy of struggle

and sacrifice. – Kwameh Nkrumah,

Politics in Uganda had began with the establishment of the Legislative Council in 1921. The Legco was to consist of the Governor and three officials (the Chief Secretary, the Attorney General, the Chief Medical Officer), Who formed the Executive Council and three unofficial members (two Europeans and one Asian).

No African was to sit on the Legislative Council. The Baganda stated that they had no interest in it. Asians demanded equal representation with Europeans which was not granted and they boycotted the council until Governor Sir William Gowers persuaded them to end the boycott and C.J Amin became an unofficial member of the Legislative Council in 1926. In the same year, the Directors of Agriculture and Education were included in the Council.

The Legislative Council was a small exclusive body catering primarily for the Europeans and Indians and only remotely for the Africans. Only in 1945, were there African members, one from each province appointed to it. Buganda had none.

In 1945, Uganda went through constitutional crisis. The independent spirit offered to the Baganda by the pioneer colonialist especially Sir Charles Dundas brought problems.

The strong Katikiro who was pro-British, Martin Luther Nsibirwa resigned in 1941. Samwiri Wamala replaced him. There followed a period of conflict between Wamala's opponents and the Bataka. The Bataka federation was conservative society, which aimed at preservation of Baganda's traditions. They even opposed the building of Makerere College as against Baganda tradition.

In 1945, riots broke out all over the Country. There were strikes and labour unrest. These were eventually put down by the King's African Rifles, but they were the first manifestation of nationalism in Uganda.

In Buganda, Wamala was accused of collaboration with colonialists against the Baganda and he resigned. Even disloyal members of the Lukiiko were dismissed. To be more strict with Buganda, Sir John Hall reinstated Nsibirwa as Katikiro in 1945 July.

He was assassinated on 5th September at Namirembe Cathedral. After his death, Kawalya-Kaggwa became the Katikiro. In 1946, a general election was held in Buganda

And 31 members were chosen as representatives to the new council. In 1946, riots broke out again in Buganda. They were caused by the Bataka and the African farmer's Union. They demanded a removal of some members of the Lukiiko. The mob went about looting all over Buganda. The police arrested the leaders and tried some while others were sent to Prison. The Bataka party and the African farmers' Union came to an end.

The Commission of Inquiry setup recommended constitutional reforms to bring the government and people Closer. From 1945, the central government became strong. Three African members became representatives in the Council. These were nominated from Buganda, Western and Eastern provinces. The Baganda were unco-operative with the central government

By 1950, 8 Africans were among the sixteen unofficials members of the Legislative Council

The Lukiiko was to nominate one member, but is passed on the responsibility to the Kabaka. By 1953, the number of African representatives had increased to 14, and the total Representation was 28. Busoga was still unco-operative.

FACTORS FOR GROWTH OF NATIONALISM IN UGANDA

Despite the above factors, political parties were formed in Uganda between 1945 and 1962. The reasons for this drastic change to active participation in politics were: Firstly, the Second World War (1939‑45) contributed to the growth of nationalism in Uganda. The War involved Germany, Italy and Japan against Britain, Russia, France and later USA. The Africans were taken to fight on the side of their colonial masters. The fighting took place in North Africa, Somalia, Ethiopia, South East Asia and the Pacific. On the side of Africa, there were a number of positive political effects that led to the growth of nationalism.

Secondly, the influence from Super Powers contributed to the growth of nationalism in Uganda. USA and USSR were opposed to colonialism since they did not participate directly in colonial activities. Their influence came after the World War II after the collapse of the economies of Britain, France, Germany and Italy. For a number of reasons, the two super power countries became too critical of colonial rule worldwide. The US in particular wanted to take over the market for her trade.

Thirdly, the failure of Conservative Party in Britain contributed to the growth of nationalism in Uganda. It was this party with its leader Winston Churchill that supported continuation of colonial rule worldwide. The labour party led by Atlee Clement, which came to power in 1945, did not advocate for colonialism. Labour put pressures on Britain grant self-rule to her colonies everywhere.

Fourthly, the 1945 Manchester Conference contributed to the growth of nationalism in Uganda. The 5th Pan African Congress took place in England. Outspoken and highly educated African nationalists like Kwame Nkrumah for Ghana, Jomo Kenyatta for Kenya, Dr. Hastings Kamuzu Banda for Malawi, Patrice Lumumba for Congo, Nigeria's Nnamdi Azikiwe, Guinea's Sekou Toure and Senegal's Leopold Senghor among others attended this conference. They were inspired to organise and prepare their people to struggle for independence. They advocated for independence among African countries.

Fifthly, the formation of the United Nations in 1945 led to the growth of nationalism in East Africa. This was formed shortly after World War II. The UN charter condemned imperialism in every part of the world. There was formed the decolonization and UN trusteeship council which advocated for independence of many countries.

Also the Universal declaration of Human rights was declared in December in 1948 and advocated for equality of all people contributed to the growth of nationalism in East Africa. Ugandans took this opportunity to form political parties.

Furthermore the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 contributed to the growth of nationalism in East Africa. When Italy under the leadership Mussolini invaded Ethiopia in 1935 many African nationalists were concerned and were determined to defend Africa from the new form of decolonisation.

Colonial policies also contributed to the growth of nationalism in East Africa. The internal policies of the colonialists facilitated the growth of nationalism especially where some of these policies made Africans to suffer. Over taxation; loss of fertile land; discrimination in unemployment; destruction of local political institutions; forced labour with poor remuneration; and severe harassments were some of the serious issues.

The existence of independent African states like Ethiopia and Liberia served as models for countries, which were fighting for their dignity. These two countries escaped European colonialism. Other Africans admired the freedoms the existed in independent countries.

Egyptian revolution contributed to the growth of nationalism in Uganda. The 1952 Egyptian revolution led to the fall of the monarchy and King Farouk. Gamal Nasser provided assistance to the freedom fighters in Africa. For Uganda in particular, a foreign office for UNC was opened in Cairo. Musaazi's representative there was Kalekezi. From Kigezi a father to Kale Kaihura, senior army officer andchief of Uganda police.

Independence of African new states contributed to the growth of nationalism in East Africa. The acquisition of independence for developing countries like India (1947), Ghana (1957), Guinea (1958) added force in mass political changes and formation of political parties.

Education also contributed to the growth of nationalism in East Africa. The emergence of political elites who had acquired their education in different European countries was exposed to revolutionary, intellectual and nationalistic outlook. For example Africans in UK came up with a slogan of "no taxation without representation". They learnt of new principles of peace, justice, and equality for all. They formed different associations to struggle for their independence.

The formation of Non-aligned Movement contributed to the growth of nationalism in East Africa. Non-aligned Movement refers to a group of organised developing countries that were neither aligned to the eastern bloc nor the western bloc during the cold war period. The first conference for the formation of the non-aligned movement took place at Bandung in Indonesia in 1955. It condemned colonialism and encouraged all people in colonies to struggle for self-rule.

The news of the 1952-1955 Mau Mau rebellion stepped up nationalistic feelings in Uganda.

The 1953-1955 Kabaka crisis for the first time united all Ugandans in demanding for his return.

The common hatred against the proposed East African federation led to nationalistic feelings in Uganda.

Sir Andrew Cohen's administration led to the growth of nationalism in Uganda, He was a reformer, ready to Africanise the politics of Uganda and called for a unitary government in Uganda.

The rise of the press led to the awakening of Ugandan nationalism.

The constitutional changes in Uganda forexample the appointment of 3 Ugandans to the Legco in 1945 and increasing the number to 14 in 1953 also led to the growth of nationalism in Uganda.

GROWTH OF SUB-NATIONALISM AND AFRICAN NATIONALISM

In the 1940s the people of Buganda took the lead in African nationalist politics in Uganda. Their motives were political and economic. The Baganda desired greater participation, by the appointment of more representatives, in Buganda's local parliament, the Lukiko. They hoped for the replacement of the old type of chiefs. These political demands led to riots in 1945 and the assassination of the Katikiro (Prime Minister) of Buganda, Martin Nsibirwa.

The demand of the Baganda for the right to market their own crops led to riots in 1949 against Asian and European businessmen. The riots of 1945 and 1949 were spontaneous outbursts by sections of the African population of Uganda which desired political democracy and economic freedom. The riots were carried out by Baganda but they did not represent overt Baganda sub-nationalist or ethnic nationalist feeling.

It was not until the elite took over the nationalist movement in the 1950s that ethnic sub-nationalism came to the fore both in Buganda and in the other areas of Uganda. Paradoxically, it was the attempt by Britain to weaken Bagandan separatism and create a unitary system of government for all Uganda that provoked a strong outbreak of Baganda ethnic expression in the political life of the country.

In 1952 the British Government appointed as Governor of Uganda the brilliant and comparatively young 42-year-old Sir Andrew Cohen, formerly head of the Africa Department of the Colonial Office. Almost as soon as he arrived in Uganda, Cohen proposed radical changes based on a strongly centralized system of administration and representative (elected) government. Cohen believed that the future of Uganda must lie in a unitary form of central Government on parliamentary lines covering the whole country. The Protectorate is too small to grow into a series of separate units of government, even if these are federated together.' Cohen looked forward to development of the country 'by a central Government of the Protectorate as a whole with no part of the country dominating any other part but all working together for the good of the whole Protectorate and the progress of its people'8

In 1953 Cohen introduced changes in the Legislative Council. The number of representatives was increased to 28, of whom 14 were to be Africans. In 1955 a ministerial system was introduced, but before then the "Kabaka crisis', as the British called it, had shaken the country.

In 1953 the Kabaka, (Sir Edward) Mutesa II, supported, by the Lukiko, came out in open opposition to British government policy. The confrontation was, in part, connected with questions of Buganda's autonomy in relation to the British, and also Uganda's autonomy in relation to Kenya settlers.

The precipitating factor had been a speech by the Colonial Secretary which seemed to suggest the formation of an East African Federation which, in the circumstances of the day, would have meant greater settler say in Ugandan affairs. Buganda reacted sharply to this speech, and before long there was a fusion between the issue of Buganda's rights as against the Governor, and Uganda's rights as against white settler dreams of an East African Federation.

In November 1953 Cohen deposed Mutesa and deported him to Britain in an aeroplane, for 'breaking' the Buganda Agreement of 1900 which required the Kabaka to co-operate loyally with the Protectorate Government. His deportation turned Mutesa into a nationalist hero. In the words of Semakula Kiwanuka, 'Overnight, Mutesa became a hero and acquired a measure of popularity which he had not achieved since his accession in 1940'.9

Mutesa

returned in November 1955, and signed with Cohen a new Buganda Agreement based

on the 1954 Namirembe Conferences. The agreement was a compromise. Unitarism

was confirmed, but the Kabaka secured three vital concessions: securer rule for

himself vis-a-vis a reformed Lukiko; new machinery for resolving disputes

between the Buganda and Uganda governments: and safeguards against settler

domination of an East African Federation.

Mutesa

returned in November 1955, and signed with Cohen a new Buganda Agreement based

on the 1954 Namirembe Conferences. The agreement was a compromise. Unitarism

was confirmed, but the Kabaka secured three vital concessions: securer rule for

himself vis-a-vis a reformed Lukiko; new machinery for resolving disputes

between the Buganda and Uganda governments: and safeguards against settler

domination of an East African Federation.

Cohenist unitarism triumphed but the Baganda and their leaders were not converted to it. The Baganda saw the return of the Kabaka and the new agreement not as reconciliation with the British but as a victory over them. This attitude on the part of the majority of the Baganda was to make the evolution of a united nationalist movement in Uganda almost impossibility.

A major step in Uganda's political progress was the introduction of direct elections in 1958, to Legislative Council, which now had an African majority (15 out of 25). However, the Kabaka and the traditional chiefs in the Lukiko feared the advance of democracy as much as unitarism and a non-Ganda majority in the country as a whole, and they arranged that instead of direct elections in Buganda the Lukiko would nominate Buganda's representatives to the Legislative Council. Ankole, another traditional kingdom, also adopted indirect elections to the Council.

Further constitutional progress was made, in spite of the opposition of the traditional Baganda leaders, with the 1959 Wild Committee and Report, which recommended a common roll and abolition of indirect elections, in preparation for independence. The Wild Committee's work had the effect of stimulating both Baganda sub-nationalism and Ugandan nationalism.

The

first effect was the rise of the Ugandan National Movement (UNM) which

organized a boycott against non-African traders in 1959, in an effort to

restore to Buganda the leadership of the Ugandan nationalist movement. The

second effect was the emergence in 1959 and I960 of the Ugandan People's

Congress (UPC), the strongest splinter group of the UNC and a multi-ethnic

party relying on non-Ganda support in the north, east and west of the country.

The

first effect was the rise of the Ugandan National Movement (UNM) which

organized a boycott against non-African traders in 1959, in an effort to

restore to Buganda the leadership of the Ugandan nationalist movement. The

second effect was the emergence in 1959 and I960 of the Ugandan People's

Congress (UPC), the strongest splinter group of the UNC and a multi-ethnic

party relying on non-Ganda support in the north, east and west of the country.

The UPC was led by Apolo Milton Obote, who was descended from a chiefly family in Lango, had been educated at Makerere, and was basically a member of the new middle-class nationalist elite. What held the disparate ethnic elements of the UPC together was the common bond of anti Ganda feeling. Indeed Buganda's brief enjoyment of dominance during the colonial period had played an important part in the integrative process in Uganda.

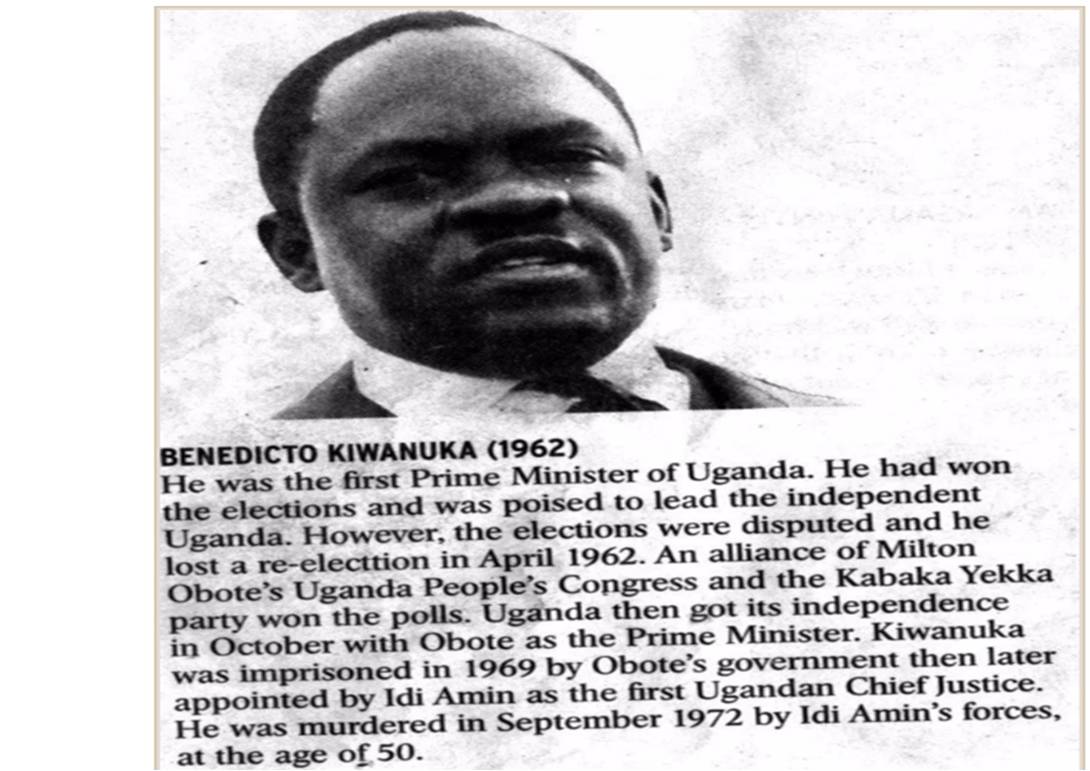

The March 1961 elections to the National Assembly resulted in 44 seats for the Democratic Party and 35 for the UPC. The DP majority was artificial. Kiwanuka's party won 20 out of 21 seats in Buganda only because the Kabaka's government declared it would be disloyal to the Kabaka to register to vote. As many as 97 per cent of the Baganda of voting age observed the boycott. However, the DP had a majority of seats and Kiwanuka became Chief Minister.

Kiwanuka's victory at a national level represented an attempt by one group of Baganda to come to terms with the new forces of Uganda-wide nationalism. In this sense Kiwanuka was serving Buganda's real interests. However, in Buganda as a whole there was little understanding of Kiwanuka's purpose or appreciation of his achievement. As F.B. Welbourn has written;

Kiwanuka's position was acutely difficult. In England, while the Kabaka was in exile and Kiwanuka a student of Law, they had been good friends. But in Buganda he was not only a Catholic, he was a mukopi, a peasant, a nobody, a phrase used openly at this time by English-speaking Ganda. For any Ganda to claim - as the Chief Minister of Uganda must claim to be in the long run above the Kabaka was treason.10

As Welbourn goes on to write, in Buganda the DP was seen as a fundamental threat to the Kabakaship itself, to the living roots of Buganda's future. Its members were nabbe, the red ant which destroys the termites. In contrast the Kabaka was nnamunswa, the queen termite who protects her brood.

In reaction to Kiwanuka's victory in the national elections, the Kabaka's government formed the Kabaka Yekka ('King alone') party, whose aim was toprevent the DP destroying Buganda's special position within Uganda.

In the February 1962 elections to the Lukiko, the KY won 58 seats and the DP won only two. The KY took the option, which still remained, for Buganda co nominate Buganda's representatives to the National Assembly instead of having them elected directly. In March 1962 Kiwanuka became the first Prime Minister of Ugandaunder internal self-government.

Independence was planned for October but in terms of practical politics the major event in 1962 was the pre-independenceelections in April.

To the surprise of many observers Obote's apparently more radical UPC concluded an electoral alliance with the seemingly feudalistic KY. The elections produced 44 seats for the UPC, 21 for the KY and 24 for the DP. Thus at independence Uganda was governed by an unlikely UPC-KY coalition, with Obote as Prime Minister and Mutesa as President.

Obote's policy at this Stage of his political career was to retain some link with the inevitabilities of history to keep some ties with the residual pre-eminence of the Baganda on attainment of independence. Uganda as a whole did not have an international image as a great radical country or even as a militantly pan Africanist state, but the nearest thing to a radical symbol in Uganda was the UPC- And here was the party of radicalism associating itself in power with the party of conservatism and traditionalism. It was a concession, on Obote's part, to an ethnocentric heritage.

Obote supported the election of Sir Edward Mutesa as President of the country, while Sir Edward retained his position as Kabaka of Buganda, as a shrewd tactical political move. Inevitably, it would complicate the loyalties of Sir Edward to entrust him with responsibilities which would force upon him the broader national cause, as well as the narrower one of his own ethnic kingdom.

Ultimately, however, since the UPC-KY pact was one of convenience not conviction, a pact of understanding to share positions in the new Uganda, but which papered over the ultimately irreconcilable differences between a unitarist party and a federalist one, the pact was almost inevitably bound to break sooner or later.

The Obote-Mutesa relationship was comparable to that between Lumumba and Kasavubu in the Congo at independence: either the advocate of a strong central government and non-ethnic nationalism would prevail over the federalist/regionalist sub-nationalist, or the latter would prevail over the former. There the comparison ends, for the outcome was different in each country.

WHY NATIONALISM CAME LATE IN UGANDA

The system of indirect rule as well as the divide and rule policy which divided the people along tribal, religious and racial lines. The colonial practice of divide and rule was imposed to reduce social interaction and the emergency of collective consciousness among the oppressed people.

There were no common nation‑wide burning issues among the people like it happened in Kenya and Zimbabwe. The problems in Uganda were local and affected small groups of people.

Uganda being a heterogeneous nation, people could not easily unite against the foreigners. The economic backwardness among Ugandans contributed to the delay in party formation. Some people lacked transport to move and even getting information for easy mobilisation. It became difficult without funds. This was one factor that also divided the politicians. They kept on doubting the efforts of other religious groups. Protestants could not co-operate with the Catholics and vice versa.

By then, few Africans had acquired formal education while the majority was ignorant about the politics of Uganda.

There was the problem of language barrier that made it difficult for people to understand each other.

Little exposure to freedom fighters worldwide may have contributed to the delay.

The Africans who participated in leadership were not ambitious for political posts because they were contented with the positions they held.

The traditional leaders opposed the formation of political parties in Uganda. Especially in Buganda, parties were seen as a threat to the Buganda monarch and its special position accorded to her by the Buganda agreement of 1900. The defeat of earlier resistances like the Nyabingi rebellion in Kigezi, the Lamogi rebellion in Northern Uganda and Nyangire-Abaganda rebellion in Bunyoro in Uganda made the would‑be nationalists to shy away.

The British favours on Buganda hindered mass nationalism in Uganda till the 1950s. In pursuit of their indirect rule, the British sent a number of Baganda agents to rule other tribes for example Semei Kakungulu was sent to Eastern Uganda, James Miti to Bunyoro, etc. This created anti-Baganda sentiments in Uganda to make matters worse, the British rewarded their Baganda collaborators with social economic developments such as good schools, hospitals and roads. This made them proud and brewed the jealousy of other tribes towards Buganda. Mass nationalism had to delay.

Colonial developments such as roads, urban centres, schools, hospitals and factories made Ugandans generally friendly and loyal to the British colonialists. The British colonial economy made most Ugandans busy cultivating cash crops as coffee, cotton and tea. They were pre-occupied with the desire to become rich and had no time for politics. Hence delayed nationalism.

Most elites were colonial puppets. The British provided employment opportunities to the elites in the colonial civil service. Such Africans were prevented from joining politics and any who did were retrenched from the colonial jobs. This made most elites to shy away from politics and hence delayed nationalism.

The absence of trade. The British discouraged the formation of trade unions because they could enlighten Ugandans. The few, which existed, were in Buganda and were religiously divided.

The limited nature of the press. The earliest newspapers were written in one language- Luganda for example "Uganda Eyogera", "Munno" etc. These only appealed to the Baganda monarchical sentiments.

The delay of political parties. The British did not favour the formation f political parties and even when these emerged later, the British promoted religious divisions between them. This prevented unity and hence delayed independence.

The absence of Asian and European politics in Uganda also led to delayed nationalism in Uganda. Unlike south Africa or Southern Rhodesia where whites formed political parties, there were no such exposures for Ugandans. Even the Asians were pre-occupied with business and not politics. So, Ugandans took long to gain the concept of political parties.

The harsh reaction of the British to riots led to delayed nationalism in Uganda for example the 1945 and 1949 riots in Buganda were crushed violently and this scared a number of nationalists all over Uganda.

The ideological differences between the newly formed parties also delayed the independence of Uganda e.g. the UNC and UPC became socialist oriented due to the activities of strong socialist members e.g. Change Macho, Bidandi Sali, Kirunda Kivejinja among others. The DP was capitalist while the Uganda National Movement was positive in action. Such differences led to delayed nationalism.

The slow rate of urbanisation also hindered quick nationalism. The majority of Uganda's population was rural based, poverty-stricken and couldn't finance political party activities.

Buganda's secessionist tendencies also hindered the growth of nationalism in Uganda. Buganda which had the best social and economic infrastructure wanted to break away from the rest of Uganda. It was opposed to unitarism and favoured federal government. This provoked the jealousy of other tribes.

The absence of charismatic leaders. The majority of earlier politicians can be termed as "week-end politicians" who had their full time jobs as teachers, doctors, businessmen and lawyers. They only converged on week-ends in suburbs like Katwe to discuss politics. Hence lack of full time politicians and political leaders led to delayed nationalism.

Lastly, the leaders of the political parties were not full time politicians. They were "Weekend Politicians" mostly comprising of teachers, lawyers, doctors and businessmen who were engaged on their professional duties from Monday to Friday but participated in politics on free weekends only.

BUGANDA'S SECESSIONIST ATTEMPTS

Between 1952 - 1966, Buganda made efforts to break away from the rest of Uganda and form an autonomous state. This was due to the following reasons:

To protect her traditional independence. Before colonial rule, Buganda was politically, economically and socially strong and independent. Her system of administration was so good and admired by the British who applied it in other parts of Uganda (Kiganda model of administration). Their attempt to secede was therefore aimed at maintaining their traditional status.

To protect her uniqueness. By the terms of the 1900 Buganda agreement, Buganda had been given a favourable position and a special status as compared to other Kingdoms of Uganda. And throughout the colonial period, they had been favoured. By seceding, Buganda hoped to retain her unique status.

The Kabaka's powers, respect and dignity would only be retained if Buganda seceded from the rest of Uganda. A unitary government or the East African federation would reduce his powers.

Opposition against Cohen's Unitarism. Sir Andrew Cohen proposed the formation of a unitary form of government in Uganda. As for Mutesa II, he wanted a federal type of government and when Andrew Cohen refused Buganda opted to secede.

The fear of the East African federation also led to Buganda's attempts to secede. In 1953, the British colonial secretary (Lyttelen) declared the British intentions of creating a federation/ political union of Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyika. Buganda feared that this would lead to grabbing of land by the white settlers of Kenya- Hence the desire to secede from Uganda.

Buganda wanted to protect her culture. Buganda feared that both the E.A.F and the unitary government would undermine her culture. Already, peoples of other tribes had started coming to Kampala and if this trend weren't checked, it would render Buganda's superior culture diluted- Secession was aimed at protecting her culture.

The desire to protect her resources. Buganda was richer and superior to other provinces of Uganda by then. She feared that uniting with other provinces of Uganda would make her resources to be diverted to developing those other parts. This would slow down Buganda's development. Hence her desire to secede.

Buganda felt self-sufficient. With her natural endowments, good climate, trade and the colonial developments like schools, hospitals, roads and towns; Buganda felt she was strong enough to manage its own affairs. It felt adequate and needed no-body hence the rejection of unitarism and opting for secession.

Buganda wanted to protect its land from the many immigrants who were trickling into the Kingdom on a daily basis. These included some whites and Ugandans, but mostly the Asians who were buying land from poor Baganda.

The question of the lost countries also led to Buganda's desire to secede. In appreciation of the great role the Baganda had played in crushing Bunyoro's resistance and extending colonial rule to the rest of Uganda, the British had rewarded the Baganda with 10 counties of Bunyoro- the lost countries.

The introduction of democracy in Uganda was feared by Buganda because it would reduce the Kabaka's powers. Hence Buganda's boycott of the 1958 direct elections and the continued desire to secede. Buganda equally feared the Wild committee's recommendations.

Failure of the British to protect Buganda led to her secessionist demands. In 1945 and 1949, the British had used force against the Baganda and in 1953, Cohen had exiled the Buganda King. The Baganda could no longer count on British protection.

The hatred from other tribes made Buganda desire to secede. Why unite with other tribes who hated Buganda?

REASONS FOR BUGANDA'S FAILURE TO SECEDE

Lack of support from elites. The young Baganda elites like Abu Mayanja, Ben Kiwanuka and Ignatius Musaazi did not bless Buganda's secessionist demands; hence its failure.

The British determination to create a unitary state led to the failure of Buganda's secession. Governor Cohen and his successor Fredrick Crawford insisted that Uganda was too small to be fragmented into small units of government.

The deportation of the Kabaka in 1953 had an effect of intimidating both the conservative diehards and the Kabaka himself. On his return, he was no longer very vocal and this led to the failure of the secession.

The absence of a strong army to back up Buganda's secessionist demands led to its failure. Compared to Eritrea which seceded from Ethiopia using force of arms, Buganda lacked a strong army.

Buganda's central position undermined her secessionist attempts. The Kingdom was geographically located in the central part of Uganda and had enormous resource endowments such as Lake Victoria fish grounds and fertile agricultural soils. She also had several up to date schools, hospitals and roads. Other tribes couldn't allow her to secede.

Divisions within the Lukiiko undermined Buganda's secessionist efforts. There existed divisions between the supporters of the Kabaka and collaborators of the British within the Lukiiko. Since a number of Ganda wanted favours from the British, they betrayed Buganda's secessionist move.

The 1954 Namirembe conference led to the failure of Buganda's secession. It was organised by Sir Keith Hancook and was attended by key figures in Buganda like Bishop Joseph Kiwanuka. It recommended that Buganda be integrated into the rest of Uganda and this was a big blow to Buganda's secessionist attempts.

The rise of anti-Baganda parties undermined Buganda's secession. Political parties with anti-Ganda sentiments included the DP (1954) Uganda Peoples' Union (1958) and UPC 1960.

A post-independence affair" The British termed Buganda's secessionist demands as a simple tribal affair which would be handled by the post independent Ugandan politicians. This attitude of the British led to its failure because no post-independent leader could allow Buganda secession.

The 1955 Buganda agreement Namirembe agreement led to the failure of Buganda's secession. This was because the Kabaka accepted the recommendations of the 1954 Namirembe conference by which Buganda was to be an integral part of Uganda.

Obote's political shrewdness also led to the failure of Buganda's secession. He made an alliance with the KY, allowed the Kabaka of Buganda to be the first President of Uganda. However, by obtaining constitutional powers as Prime Minister in 1962, he de-campaigned secessionism.

The Pan African Movement and the general wind of change across African led to the failure of Buganda's secession. Pan Africanists condemned parochialism in Buganda and sensitised other tribes to reject it. Even some Baganda like Ben Kiwanuka and Musaazi de- campaigned it seriously.

The 1967 constitution which abolished kingdoms finally destroyed Buganda's dreams of secession. It declared Uganda a republic and abolished the Kingdoms.

THE DEPORTATION OF THE KABAKA AND THE KABAKA CRISIS

In 1952, the British Government mooted the idea of a federation of East Africa and all the Kingdoms rejected it. However, Buganda's response was the strongest. The Kabaka responded by asking for the 'independence' of Buganda from Uganda.

This request was rejected by the Protectorate Government, which responded by deporting Kabaka Mutesa on 30 November 1953, on the charge that he had refused to co-operate with the British Government as per the 1900 Agreement, which had stripped him of his political powers.

The agreement had turned the Kabaka into a servant of the colonial state because he could not do anything political without the approval of the colonial rulers. The deportation of the Kabaka provoked Buganda nationalism arousing the Baganda to agitate for his return.

Also, almost all the district councils in the Protectorate passed resolutions condemning the British. As a result of increased pressure, the Governor worked out ways for his return. He proposed a conference under the chairmanship of Professor Keith Hancock. This resulted into the Namirembe Conference of 1954, which formed the basis for the return of the Kabaka on October 17 1955.

Sir Fredrick Edward Mutesa Walugembe II was crowned the 37th Kabaka of Buganda in November 1942 and was claimed His Highness Mutesa II, by the Anglican Bishop of the protectorate of Uganda.

For his education, Mutesa attended King's College Buddo where he interacted with friends like Daudi Ochieng. Later after his coronation, he went to Makerere College for a degree course. From there he went to Cambridge University in England to study history and colonial administration.

Kabaka Edward Muteesa II (C) upon his return from two years of exile in Britain on October 18,1955.

When he left Cambridge he served for a short time with the Grenadier Guards, one of Britain's most famous fighting regiments who guard the Buckingham Palace. In this force, Mutesa was promoted to the rank of Cap tain.

CAUSES OF THE 1953 KABAKA CRISIS

There Kabaka crisis had many causes but the paramount ones include the Failure to co-operate with the British. Ever since Mutesa ascended to the throne after death of his father King Daudi Chwa in 1939, he refused to act according the 1900 Buganda agreem ent.

Second, the Proposal for formation of the East African Federation. The people of Baganda and their king actually feared loss of land to settlers as it happened in Ke nya.

Third, the desire of Buganda to become independent. In August 1953 Mutesa went ahead to ask for the independence timetable. He was doing what his people wante d.

Fourth, the king wanted to change the Buganda agreement, which trimmed off his pow ers.

Fifth, the increasing superiority of Buganda under Mutesa since he came the throne in 1 939.

Sixth, the withdraw of support from the Kabaka by the Luk iiko.

Another cause was the governor's decision to transfer the nomination of Buganda's representatives to the Legico. Mutesa was not happy with the governor when he gave the Lukiiko power to nominate Buganda's representatives to the Lukiik o.

Furthermore the newly formed political parties were against the suggested East African federa tion.

Personality differences. The two men Kabaka Mutesa II and Sir Andrew Cohen had divergent personalities. The Kabaka was a conservative monarch interested in protecting the interests of the Baganda while Cohen was a modeniser. There was no way the radical Cohen could accommodate the out dated views of Kabaka Mutes a II.

It was a result of colonial legacy. The British had given a number of priviledges to the Kabaka and the Baganda in general. However, the Buganda agreement of 1900 had reduced the powers of the Kabaka e.g the Kabaka could no longer pass any new laws in his Kingdom without consulting the British . The British could also dismiss the Saza chiefs without consulting the Kabaka. To Mutesa II, this was tantamount to loss of his powers and was unacceptable. Hence the 1953 - 55 cr isis.

Disloyalty to the governor. By the terms of the 1900 Buganda agreement, the Kabaka was expected to be loyal to the British governor/central government. However, ever since Andrew Cohen's arrival in Uganda in 1952, the Kabaka had constantly questioned the decisions of the new governor. This led to his deportation He had breached the 1900 agree ment.

Cohen's Unitarism led to the Kabaka crisis. In his reform agenda Sir Andrew Cohen intended to turn Uganda into a unitary state. However, Kabaka Mutesa 11 rejected the integration of Buganda into a wider Uganda. He instead called for secession/independence of Buganda or a federal government. Cohen couldn't allow this and hence the cr isis.

The rejection of Cohen's legislative reforms also led to the deportation of the Kabaka. In October 1953, Mutesa II influenced the Lukiiko to reject the nomination of Buganda's representatives to the Legco. To worsen matters, he also influenced his fellow Kings of Tore, Ankole and Busoga to reject the nominations to the Legislative Assembly. He even attempted to influence the UNC top brass to reject the British proposals. All these annoyed Andrew Cohen to the extent of deporting the Kabaka. Mutesa 11's demands for secession persistently annoyed Cohen. When Mutesa threatened to use force, Cohen concluded that the King deserved deporta tion.

Mutesa II's desire to become a hero also earned him a deportation and hence the crisis. Inspired by the traditions of Kabaka Mwanga's resistance against the British (1894 - 97), Mutesa II became determined to follow in the footsteps of his ancestor who was a hero, but this led to his deporta tion.

Mutesa II s rejection of the East African federation plans led to the 1953 crisis. On 20th June 1953, the British secretary of State, Oliver Lyttellen announced that Britain was going to create a unification of her three East African colonies. This was unacceptable to the Kabaka of Buganda who feared that the Kenyan white settlers could encroach on Buganda's land. More over, he felt that he had to be consulted first before announcing such a plan in London. This annoyed Cohen who deported him.

Both men were hard-liners with neither of them ready to concede to the other's ideas. The religious conflicts in Bu ganda

EFFECTS OF THE CRISIS

In the first place there was wide spread discontent in Buganda because people did not like it.

Secondly, it promoted unity among the Baganda because they had identified a common en emy.

Thirdly, signing of the second Buganda agreement which was known as the Namirembe agreement. It reduced King's powers a lot m ore.

Fourthly, there were demonstrations and trade boycotts in Buganda as well as men who left the beards to grow without shaving until Mutesa came back. The British felt insec ure.

Furthermore, More Africans were appointed into British colonial administration in Ug anda.

Also the number of representatives to the Legco was increa sed.

It promoted the growth of nationalism in Uganda. The Kabaka finally emerged as Hero in Bug anda.

There was formation of new political parties, which had the agenda of struggling for the return of the K ing.

The position of Kabaka was somehow challenged such that some people started minimizing him until he was finally expelled from Uganda in 1966.

Other effects were that it seriously undermined and terminated the Buganda agreement of 1900. By disrespecting each other, both the Kabaka and governor Cohen broke the agreement and rendered it null and v oid.

Kabaka Mutesa II was deported to London where he stayed for two ye ars.

It led to strained relations between Britain and their former Baganda collaborat ors.

It influenced the British to speed up the independence of Tanganyika- more so because even in Kenya, the Mau Mau rebellion had broken out at the same time of the Kabaka cr isis.

THE NAMIREMBE AGREEMENT

This agreement was signed at a conference held at Namirembe in Kampala from June to September 1955 between the British and the Baganda. It was chaired by an Australian born Professor John Hancock. The following were the major terms of the agreement:

The kabaka's powers were modified so that he became a constitutional monar chy.

The majority of the Lukiiko members were to be elected by the saza counc ils.

The Kabaka's ministers were to be appointed by the Lukiiko, subject to the governor's appro val.

Buganda was to remain part of Uganda was to sent members to the Le gco.

Nothing was to be done about closer union unless the East African people wanted it. Mutesa could return if the Lukiiko invited him.

Finally on the 17th October 1955, Kabaka Mutesa returned to his joyful people who were eagerly waiting for him.

FINAL STAGES TO INDEPENDENCE OF UGANDA (1959 - 1962)

In 1959, the governor, Sir Fredrick Crawford appointed a constitutional committee that was chaired by Mr. J V Wild. This committee was to draw plans for the 1961 general elections. Buganda refused to nominate members to the committee.

The Wild report was presented in February 1960 and proposed direct elections to LEGICO based on adult suffrage of one-man one vote. Uganda was to be granted her self-rule after the 1961 elect ions.

Buganda leaders opposed the recommendations from the Wild report and the King left for London. He wanted to postpone the direct elections to the Legco and also to separate Buganda from the rest of Uganda. The Kings of Ankole, Toro and Bunyoro supported him but their councils did not support them.

The king's mission to London was a failure and when he came back he demanded for Buganda's separate independence and threatened to have it on 31st December 1960. Buganda decided to boycott the 1961 elect ions.

The colonial administrators demanded countrywide elections, which were held in 1961. However, the Buganda Lukiiko, which was against direct elections for fear of a Catholic victory, boycotted the elections. The boycott was carried through by intimidation and harassment of all those who turned up for voter registration. Consequently, voter turn-up in Buganda was very low. The Democratic Party won 19 seats in Buganda and a further 24 seats outside Buganda. UPC won 35 seats outside Buganda. As a result, Benedicto Kiwanuka of the DP became the first Chief Minister of Ug anda.

The elections were organized in Uganda under the Umbrella of the British colonial government. DP won with 43 seats against UPC's 35. Kiwanuka became Uganda's chief minister and on 1st March 1962, he was declared the first Prime mini ster.

The fear of the catholic dominated government which people thought would revenge against the Protestants for their past frustrations led to some changes such that DP was not allowed to lead Uganda after independence. This drew the attention of the protectorate government, which set up a special committee to consider the future of Ug anda.

In order to defeat DP in the next elections, there was an alliance between the UPC, a republican anti‑monarchy party and KY, a traditionalist feudalist pa rty.

The alliance was a temporally arrangement to enable both sides come to power. This was facilitated by the fact that both parties were for Protestants; KY was weak and therefore, needed support from elsewhere; Buganda had to defend itself by getting support from the popular party, UPC and also the members of UPC and KY had attended the same Protestant schools. All these factors made it easy for the alliance to take place. Daudi Ochieng played a major role to create the alli ance.

One of the terms of the alliance which was later on adopted in 1962 constitution, was for Buganda to hold indirect election for Buganda's representatives to national parliament. UPC was not to field candidates in Buganda to allow KY compete with DP onl y.

The UPC and the colonial government supported this move. DP openly opposed this but no fair change was made. In the February 1962 Lukiiko elections, KY de-campaigned DP reasoning that voting for DP meant disrespect for the Kabaka. In other words it was a choice between Ben and Edw ard.

As expected KY won 67 Lukiiko seats with DP winning only 3. The Lukiiko then nominated 21 to go national parliament. This unfortunate event marked the failure of DP to come to p ower.

The independence elections for the rest of the country were held in March 1962 and the results were as follows: UPC won 34, KY 21 (nominated from Lukiiko) and DP 24. The KY/UPC alliance had a total of 55 seats against DP's 24 only. Most DP heavy weights in Buganda including the leader of the party, Ben Kiwanuka lost their seats.

On 9th October 1962, the Duke of Kent representing Her Majesty the Queen of England handed over the constitutional instruments of Independence to Uganda with Obote as a Prime Mini ster.

People of Uganda were to be represented equally in the National Assembly. Buganda was to be allowed twenty one members as representatives in the National Assemb ly.

The International Affairs of Buganda were to be administered by the Baganda themselves. The other Kingdoms in Uganda : Toro, Ankole and Bunyoro did not have as much power as Buganda as regards to internal affairs of their individuals regions. In 1962 another election was conduct ed.

The Uganda Peoples Union allied with Kabaka Yekka, a political party formed in Buganda and won an overwhelming majority. Dr. Apollo Milton Obote became the nominal President of Uganda with no executive powers.

UGANDAN NATIONALISTS AND FREEDOM FIGHTERS

Musazi was born in 1902, son of a Gombolola chief in Bulemezi. He was educated in mission schools and went as far as St. Augustine's school Canterbury, Engl and.

He was a teacher at King's College Buddo and later became an inspector of schools from 1934 to 1 936.

He founded peasant farmers' voluntary organisation and became the president of the federation of African Farmers, which was banned la ter.

He in 1952, together with others like Abu Mayanja and J.W. Kiwanuka founded the Uganda National Congr ess.

He enabled UNC to become the first Uganda wide political organisation whose basic demand was " self government now&qu ot;.

The UNC's membership cut across religions, regional and ethical lines .

It therefore became the champion of Uganda's independe nce.

Under his leadership UNC became involved in struggles based on access to credit facilities, land and the rule of chi efs.

UNC broke up into the Obote led and Musaazi led foundation in 1959, UNC also organised demonstrations and strikes. All in all, Musaazi struggled for the independence of Uganda

Dr. Apollo Milton Obote

Dr Apollo Milton Obote is a Ugandan politician born in 1926 at Akokoro in Marusi county, Lango district. His father Mzee Stanley Opeto was Gombolola chief who rose from a position of a poor peasant farmer. Obote looked after cattle and goats at home before joining school.

He was educated at the Lira Protestant School in Lango district then later on attended Gulu high school. His attempt to join St. Mary's College Kisubi was fruitless due to a high level discrimination between Protestants and Catholics at that time. He finally joined Busoga College Mwiri in Jinja where participated actively in students politics. The school environment had had a great impact on Obote. He was very intelligent and academically strong that is he made it to Makerere,

Obote joined Makerere University College where he undertook a Bachelor of Arts degree. He became secretary of the Makerere political society which criticized the British system of leadership and education. They also led a food strike. I948, Obote was expelled from the university. He therefore never completed his course.

He was offered a scholarship to study law in America but the colonial government turned it down. Subsequent scholarships to London and Gordon College - Khartoum were likewise turned down.

In 1948, he moved around to look for a job. He joined Mowlem construction company which by then had the headquarters at Jinja before shifting to Kabete near Nairobi in Kenya. While in Kenya, he left Mowlem and joined the standard Vacuum Company.

Obote returned home in 1957 to put the politics he had learned into practice. He became a member of the Uganda National congress (UNC) in Lango district. Ignatius Musazi, the founder of the party appointed him to represent Mb ale.

He was also elected to the legislative council (Legco) in 1958 where he became very influential. He replaced Yekosefati Engur who was stopped by the British for causing disorder in Lango.

His influence led to the formation of the electoral members' organization within the cou ncil.

In 1959, Obote split from the UNC and joined the Uganda People's Union (UPU) which was formed by non Baganda such as Wilberforce Nadiope, Obwangor, Rwetsiba and John Babiiha. In 1960 the party became UPC whereby Obote became its leader up to d ate.

Obote's skillfulness was exhibited during the London Conference when he advocated for full independence through direct and indirect elections for Buganda and the rest of Uganda respecti vely.

After loosing election in the Legislative Council (Legco) to DP in 1961, he became the opposition leader in the Legislative Council (parliament). While in the Legco, he demanded for an immediate advance to independence for Uganda. He also convinced the colonial officers in Uganda that since the 1961 elections which DP won were largely boycotted by people, it was necessary to hold more elect ions.

When the Baganda formed a political organization called Kabaka Yekka. Knowing its possible influence on the political scene, Obote used his fellow Northerner, Daudi Ocheing to negotiate with the Mengo traditionalists to form an alliance between UPC and KY in order to defeat a Catholic dominated DP. Mutesa accepted the alliance January 1962.

As a result of his demand, elections for independence were conducted in March 1962, where UPC defeated DP with 34 seats in parliament against 24 for DP and 21 for KY. UPC/KY alliance had a total of 55 seats in parliament. KY MPs were just nomin ated.

Obote formed a Coalition government with KY and in October 1962, he became Prime Minister with the entire executive and constitutional powers while King Sir Edward Mutesa II became the presi dent.

Obote saved the Banyoro from a kind of colonialism that was imposed onto them by the Baganda since 1900. He supported Bunyoro in a referendum that was held in 1964.

In 1964, the lost issue caused conflict between Obote and Mutesa that resulted into the collapse of UPC/KY alliance. KY and DP were convinced to cross the floor to UPC.

In 1966, a major crisis broke out that the centre could not hold. On April 15th 1966, Obote abrogated the 1966 constitution, removed all powers from the Kabaka's government and on May 24th the same year, the Kabaka's Palace at Mengo hill was attacked sending the Kabaka into exile and marking the end of a long traditional monarchy unceremoniou sly.

In 1967, a new constitution for Uganda was made that led to the abolition of kingdoms and federal status for Buganda. All Ugandans were considered equal irrespective of birth or origin. In 1967, Obote together with Julius Nyerere of Tanzania and Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya formed the East African community that provided the best services in the re gion.

In 1969 he declared Uganda a single party state with UPC as the only party with aim of promoting national unity. The common man's charter, which was a socialist line of development for Uganda as well as nationalization programs were laun ched.

In 1971 while attending a Common Wealth conference in Singapore, a coup d'etat carried out by Amin overthrew him from power. Britain and Israel played a role in his down fall.

He fled to Tanzania where he was received by his friend Nyerere and was accorded a title of head of state for a period of Eight years he spent there. He reorganized his UPC and other Ugandans in exile to fight Idi Amin. With the assistance Tanzania, Amin was defeated in 1979. This was an opportunity for Obote to come to power a gain.

Obote returned to Uganda on 27th May 1980 and landed at Bushenyi. He praised himself as the only African president who was overthrown and was able to come back. In an election conducted in December 1980, he won the elections. Typical of Obote's skilful manoeuvres, he was installed as President for the second time on December 15th 1980 after a general election in which his party UPC was declared wi nner.

Due to the alleged election rigging by Obote, several former anti Amin liberators led by Yoweri Museveni fled to the bushes of Luwero in Buganda and started mounting a guerilla war against Obote's re gime.

Obote took a number of steps to revive the economy which was destroyed during Amin's regime. Schools, hospitals, roads were constructed though state inspired violence remained a serious pro blem.

As the guerrilla war raged on so did the tribal conflicts within the Obote army between the Acholi and the Langi. These squabbles reached their climax on July 25th, 1985 when Brigadier Bazilio Okello an Acholi announced the overthrow of Obote's regime and by so doing, bringing to an end Obote's political legacy. Obote fled to Nairobi and later to Zambian capital Lusaka where he lived and died on 10th October 2005.

Contribution of Uganda People's Congress (UPC) to Independence

The Uganda People's Congress was a political party founded by Dr Milton Apollo Obote in 1 960. It was formed from a merger of the Uganda National Congress (UNC) and the Uganda People's Union (UPU). In 1960, the party entered an alliance 'with the favourite Buganda party, Kabaka Yekka KY (King alone). The UPC-KY alliance won majority seats in parliament in the pre-independence elections. They formed government in April 1962 and led the country to independence on 9th October 1962.

In the first place UPC mobilised many Ugandans to demand for independence.

Secondly, UPC pressurised the colonial government to grantindependence to Uganda.

Thirdly, UPC provided leadership to the independencestruggle.

Fourth, after independence, under Milton Obote in 1966 UPC droppedits alliance with KY, deposed and exiled the king.

Fifth, in 1969 UPC announced its Common Man's Charter, which transformed it into a socialist partymaking Uganda a communist country.

Furthermore UPC became Uganda's only legal party.

Unfortunately in January 1971, it was ousted by the coup tfetat of General Idi Amin Dada. While in exile it joined with Uganda National Liberation Front (UNLF) and deposed the dictatorship of Amin in April 1979.

After the December 1980 elections It assumed power for a second time.

Again in July 1985 it lost power to General Tito Okello Lutwa.

OTHER IMPORTANT HISTORICAL EVENTS IN UGANDA

1500 – Bito dynasties of Buganda, Bunyoro and Ankole founded by Nilotic-speaking immigrants from present-day southeastern Sudan.

1700 – Buganda begins to expand at the expense of Bunyoro.

1800 – Buganda controls territory bordering Lake Victoria from the Victoria Nile to the Kagera river.

1840s – Muslim traders from the Indian Ocean coast exchange firearms, cloth and beads for the ivory and slaves of Buganda.

1862 – British explorer John Hanning Speke becomes the first European to visit Buganda.

1875 – Bugandan King Mutesa I allows Christian missionaries to enter his realm.

1877 – Members of the British Missionary Society arrive in Buganda.

1879 – Members of the French Roman Catholic White Fathers arrive.

1890 – Britain and Germany sign treaty giving Britain rights to what was to become Uganda.

1892 – Imperial British East Africa Company agent Frederick Lugard extends the company’s control to southern Uganda and helps the Protestant missionaries to prevail over their Catholic counterparts in Buganda.

1894 – Uganda becomes a British protectorate.

1900 – Britain signs agreement with Buganda giving it autonomy and turning it into a constitutional monarchy controlled mainly by Protestant chiefs.

1902 – The Eastern province of Uganda transferred to the Kenya.

1904 – Commercial cultivation of cotton begins.

1921 – Uganda given a legislative council, but its first African member not admitted till 1945.

1958 – Uganda given internal self-government. Elections held in 1961 – Benedicto Kiwanuka elected Chief Minister.

1962 – Uganda becomes independent with Milton Obote as prime minister and with Buganda enjoying considerable autonomy.

1963 – Uganda becomes a republic with Buganda’s King Mutesa II as president.

1966 – Milton Obote ends Buganda’s autonomy and promotes himself to the presidency.

1967 – New constitution vests considerable power in the president.

1971 – Milton Obote toppled in coup led by Army chief Idi Amin.

1972 – Amin expels Israelis giving them 2 weeks to leave.

1972 – Amin orders Asians who were not Ugandan citizens – around 60,000 people – to leave the country in 3 months.

1972-73 – Uganda engages in border clashes with Tanzania.

1976 – Idi Amin declares himself president for life and claims parts of Kenya.

1978 – Uganda invades Tanzania with a view to annexing Kagera region.

1979 – Tanzania invades Uganda, unifying the various anti-Amin forces under the Uganda National Liberation Front and forcing Amin to flee the country; Yusufu Lule installed as president, but is quickly replaced by Godfrey Binaisa.

1980 – Binaisa overthrown by the army.

1980 – Milton Obote becomes president after elections.

1981-86 Following the bitterly disputed elections, Ugandan bush war fought by National Resistance Army

1985 – Obote deposed in military coup and is replaced by Tito Okello.

1986 – National Resistance Army rebels take Kampala and install Yoweri Museveni as president.

1993 – Museveni restores the traditional kings, including the king of Buganda, but without political power.

1995 – New constitution legalizes political parties but maintains the ban on political activity.

1996 – Museveni returned to office in Uganda’s first direct presidential election.

2000 – Ugandans vote to reject multi-party politics in favour of continuing Museveni’s “no-party” system.

2001 January – East African Community (EAC) re-inaugurated in Arusha, Tanzania, laying groundwork for common East African passport, flag, economic and monetary integration. Members are Tanzania, Uganda and Kenya.

2001 March – Museveni wins another term in office, beating his rival Kizza Besigye by 69% to 28%. Campaign against rebels

2002 October – Army evacuates more than 400,000 civilians caught up in fight against cult-like LRA which continues its brutal attacks on villages.

2003 May – Uganda pulls out last of its troops from eastern DR Congo. Tens of thousands of DR Congo civilians seek asylum in Uganda.

2004 December – Government and LRA rebels hold their first face-to-face talks, but there is no breakthrough in ending the insurgency.

2005 July – Parliament approves a constitutional amendment which scraps presidential term limits. Voters in a referendum overwhelmingly back a return to multi-party politics.

2005 October – International Criminal Court issues arrest warrants for five LRA commanders, including leader Joseph Kony.

2006 February – President Museveni wins multi-party elections, taking 59% of the vote against the 37% share of his rival, Kizza Besigye.

2006 August – The government and the LRA sign a truce aimed at ending their long-running conflict. Subsequent peace talks are marred by regular walk-outs.

2007 March – Ugandan peacekeepers deploy in Somalia as part of an African Union mission to help stabilise the country.

2008 February – Government and the Lord’s Resistance Army sign what is meant to be a permanent ceasefire at talks in Juba, Sudan.

2008 November – The leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army, Joseph Kony, again fails to turn up for the signing of a peace agreement. Ugandan, South Sudanese and DR Congo armies launch offensive against LRA bases.

2009 The UK oil explorer Heritage Oil says it has made a major oil find in Uganda.

2009 March – Ugandan army begins to withdraw from DR Congo, where it had pursued Lord’s Resistance Army rebels.

2009 December – Parliament votes to ban female circumcision. Anyone convicted of the practice will face 10 years in jail or a life sentence if a victim dies.

2010 January – President Museveni distances himself from the anti-homosexuality Bill, saying the ruling party MP who proposed the bill did so as an individual. The European Union and United States had condemned the bill.

2010 July – Two bomb attacks on people watching World Cup final at a restaurant and a rugby club in Kampala kill at least 74 people. The Somali Islamist group Al-Shabab says it was behind the blasts.

2011 February – Museveni wins his fourth presidential election.

2011 July – US deploys special forces personnel to help Uganda combat LRA rebels.

2012 Aug- Uganda’s Stephen Kiprotich winS the Gold Medal in Marathon at the Olympics ,Uganda,s second Gold medal ever, and third Olympic medal since joining the Olympics.

8 Both passages quoted in D.A. Low, Buganda in Modern History, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London. 1 971. p. 105.

9 B.A. Ogot (ed.), Zamani, a Survey of East African History, New edition. East African Literature Bureau, Nair obi, p. 327.

10 F.B. Welbourn, Religion and Politics in Uganda 1952-1962, East African Publishing House, Nairobi, 1965. p. 25.

Licensed under the Developing Nations 2.0

A Complete East African History ebook