CHAPTER NINTEEN:CLOSER UNION OF EAST AFRICAN TERRITORIES

Closer union was an attempt by the British government to federate or unite all the three East African territories of Kenya, Uganda, and Tanganyika under one administration.

The collapse of the East African Community between 1975 and 1978 was a blow for hopes of greater unity between the nation states of East Africa.

Here we will study how the East African High Commission, set up in the colonial period as a first step towards the economic unity of the three British territories of Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyika, was transformed on the eve of independence into a more integrated Common Services Authority, but Just failed to be developed into a fully-fledged political federation.

The origins of British plans for closer union between its East African territories are found in the period after the First World War.

Colonial secretaries and governors favoured closer union for the sake of economic development. Indeed common services between Kenya and Uganda for railways, customs, defence, posts and telegraphs were started in the 1890s. After 1918 these services were extended.

In the 1920s and 30s Kenya's European settlers became strong advocates of the political union of British-ruled East Africa, partly because they hoped the area of their settlement could be extended into the highlands of Uganda and Tanganyika, and partly because they believed that the fuller integration of Tanganyika with its northern neighbours would make German demands for the return of Tanganyika less effective.

Furthermore, they hoped a settler-ruled state on Southern Rhodesian lines could be set up in East Africa. However, successive British governments maintained their commitments to develop the East African colonies as African countries.

The Kenya settlers failed to attain political power in Kenya, lei alone in East Africa. The Baganda, hitherto powerful allies of the British in Uganda, led African opposition to the settler plan for closer union and a vast while-dominated federation.

Successful co-ordination between the three territories in the Second World War in matters such as war supplies and refugees encouraged the post-war Labour government to set up the East African High Commission, which came into operation on I January 1948.

The EAHC was composed of the Governors of Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyika, an Assembly in which Europeans were over-represented, and a regional civil service of expatriates.

The Central Legislative Assembly was made up of seven High Commission officials, 15 territorial members (five from each territory, made up of one official, an African, an Asian and a European - all appointed, and a member elected by the territorial Legislative Council) and one appointed Arab member. The Commission's legislative powers covered customs, income tax, defence, railways and harbours, civil aviation, posts and telecommunications, and Makerere College in Kampala.

The EAHC was not, however, a federation. The territorial governments retained major political and administrative powers including those over justice and police, health, housing, most education; labour and agriculture.

Much of the Commission's revenue came from the territorial governments. The Commission's existence was subject to periodic review by the territorial legislatures. Each territory (in practice the Governor) could veto any executive decision of the Commission.

The EAHC was transformed because of the political changes in East Africa, such as the approach of independence and the emergence of unofficial and African majorities in the territorial Legislative Councils.

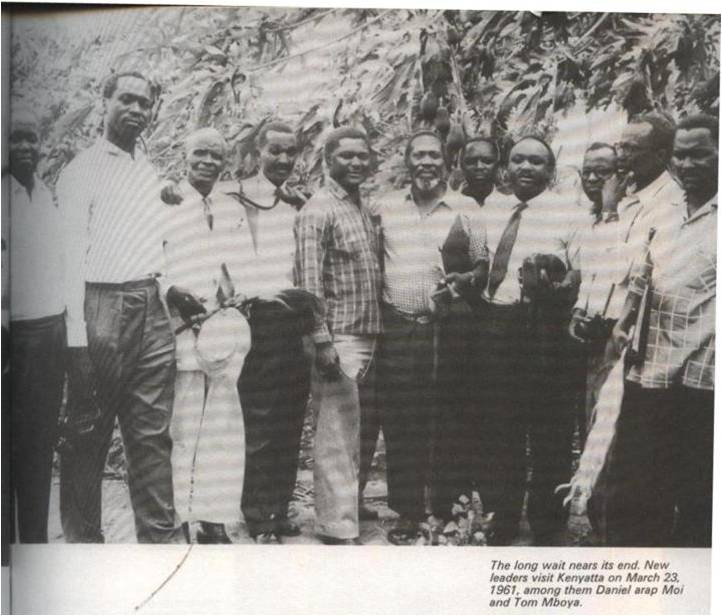

Following the I960 Raisman Commission and Report, the High Commission of governors was replaced in 1961 by the East African Common Services Authority composed of three elected leaders in each state. Under them were triumvirates of ministers from each country for communications, finance, commerce and industry, and social and research services.

The Legislative Assembly was changed, to consist now of the members of the Authority, the triumvirates, and 27 representatives, nine from each country's Legislative Council. Again, the EACSA was not a federation. Significantly defence became a territorial instead of a regional responsibility.

The African members of the territorial legislatures, inspired by the pan-Africanist spirit emanating from Accra from 1958, were eager to establish a full political and economic federation in East Africa. Unlike the Africans in the Central African Federation, the East Africans were now free of the fear of settler domination.

Also, in contrast to French-speaking West Africa, the decolonizing power in East Africa was not an obstacle to an African-led federation. Why, then, did East Africa fail to federate?

Julius Nyerere, attending the African Heads of State conference at Addis Ababa in June I960 as an observer, declared,

'We must confront the Colonial Office with a demand not, for the freedom of Tanganyika and then for Kenya and then Uganda and then Zambia, but with a demand for the freedom of East Africa as one political unit.'

He offered to postpone Tanganyika's independence for several months so that the various territories could achieve independence and unity together.

In Kenya the KANU caretaker leaders Gichuru and Mboya (Kenyatta still being in detention) supported Nyerere's proposal. But Ugandan leaders did not. The Kabaka, Sir Edward Mutesa, was doubtful about the federation of Buganda with the rest o f Uganda,leave alone federation on a wider scale.

The Uganda People's Congress president, Milton Obote, was no more enthusiastic than the Kabaka. Obote commented, 'It is futile to try to think outside Uganda before solving internal problems. In the long run the idea is attractive.' The Ugandans' attitude pro- vided London with an excuse to ignore Nyerere's proposal and delay Kenya's independence for a few more years, and Tanganyika, Uganda and Kenya became independent at different times.

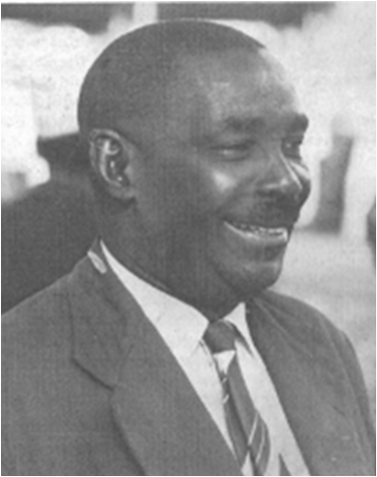

Milton Obote, founder of the UPC

Nevertheless, the East African Common Services Authority was formed in 1961. Then on 5 June 1963, four days after the achievement of Kenya's madaraka or internal self- government, and with Tanganyika and Uganda already independent.

President Nyerere, Prime Minister Obote and Prime Minister Kenyatta issued the Declaration ofFederation by the governments of East Africa.

The Declaration announced that a working party had already been set up to prepare a draft federal constitution. The following year, however, was marked by events which effectively destroyed the spirit of East African unity and placed federation outside the realm of immediate practical possibility.

In 1964 Tanganyika merged with revolutionary Zanzibar into Tanzania and moved cowards a more radical form of socialism, thereby alarming both Kenya and Uganda.

Abeid Karume, the party leader who formed the federation with Nyerere

Abeid Karume, the party leader who formed the federation with Nyerere

Nyerere and his government described Tanganyika union with Zanzibar as a step towards the goal of an East African federation. They were wrong. The narrower unification of Tanganyika and Zanzibar has harmed the ambition of a broader unification.

Nothing could have dramatized more effectively the problems which would attend a prospective East African federation than the problems which almost at once arose in relations between Zanzibar and Tanganyika. Even in external affairs it seemed doubtful that the central government in Dar-es-Salaam could speak for the union as a whole. The prolonged argument as to which of the two Germanys was to have an embassy in Tanzania was one case in point.

The moral of this whole experience is that there are occasions when a blind plunge into union is what is needed to make the union take place at all. The union of Tanganyika and Zanzibar did itself constitute such a sudden plunge. But once that took place, East Africa as a whole could no longer federate blindly - for the smaller union had opened the eyes of the region as a. whole to the difficulties involved in such a venture.

Another factor militating against the setting up of a federation was Tanzania's socialism. Ease Africa attained independence as an economic community, with a common market consisting in a flow of goods between the territories which was almost completely free, and common services which included a common currency. Both these factors became a hindrance to Tanzania as she developed a planned economy within her own borders.

At a conference on the co-ordination of economic planning in East Africa held in Entebbe on 17 March 1964, Tanzania's ministerial delegate Nsilo Nswai announced that Tanganyika was considering leaving the common market and setting up a separate currency. This helped to precipitate a crisis which culminated in the Kampala Agreement. The Agreement allowed for quota restrictions on imports from each other, and allocated specialized industries to each partner. The common-market principle in East Africa was thus seriously diluted.

Ever since 1898, it had suggested that closer union within East Africa was practical and desirable. When Johnston went to Uganda in 1899, he had been told to put in mind the possibility of merging the three East Africa states.

After

his retirement in 1905 Sir Charles Eliot had pointed out the advisability of doing so

as soon as possible, for the longer they remain apart the more they tend to

become different in administrative systems and regulations.

After

his retirement in 1905 Sir Charles Eliot had pointed out the advisability of doing so

as soon as possible, for the longer they remain apart the more they tend to

become different in administrative systems and regulations.

The truth of this statement was to be borne out in the years ahead. But the British Government hesitated and delayed, and with each passing year the development of its East African territories became more divergent.

However, the idea was revived with the acquisition of Tanganyika after the First World War.

Winston Churchill, when Colonial Secretary in 1922, declared that he looked forward to the day when a great East African Federation, almost an empire would be established. The idea was enthusiastically followed up by his successor. L.S. Amery, in 1924.

In that year a Commission under the chairman ship of the Hon. W. Ormsby - Gore was sent out from Britain to study and report on the possibility of closer union and co-ordination in East Africa.

It found a general dislike of closer union from most sections of the population and recommend that while political union was not possible for the time being there should be, through the medium of regular Governors Conferences, a move towards cooperation in matters of common interest.

These included railways and harbours, posts and telegraphs, agriculture and health. It emphasised that any moves towards federation must come from within East Africa and should not be imposed from without. What then, were the feelings of the various East African communities?

Steps taken to unite East Africa

- The idea to unite East Africa started in 1898.

- In 1900, Sir Harry Johnston again tried to federate East Africa.

- In 1901-1905, Sir Eliot supported the unification of East Africa in order to establish a common government.

- In 1920, Winston Churchill the then British colonial secretary revived the idea of creating a greater East Africa.

- In 1924, L. S Ameryset up a commission to study the closer union of East Africa. However, this committee was opposed by both Africans and settlers.

- In 1927, Sir Edward Grigg prepared a federation scheme in order to come up with a common market.

- In 1928, another survey was carried out by Hilton Young Commission but it failed.

- In 1930s, the idea was revived but without any success.

- In 1940s, the idea was dropped.

- By 1960, the British prepared to grant Independence to each East African country.

Reasons for the Closer Union

Britain wanted to unite all the three East African territories because of the following reasons.

Firstly, the encouragement given by Lugard in 1898 is what inspired Britain to unite all the East African territories. In 1900 sir Harry Johnston the British high commissioner to Uganda further encouraged Britain to unite East African states (Kenya,Uganda and Tanganyika).

Secondly, the need toestablish a common government with similar rules and regulations.

Thirdly, Britain wanted a greater East African Empire with one parliament and Judiciary.

Fourthly, the need to create a common market and common currency. The need for free movement of goods and services in East Africa.

The railway line had already united Uganda and Kenya, so the federation seemed easer also contributed.

Furthermore, the need to avoid duplication of services in the three states. Uganda and Kenya shared the same colonialmasters (the British) i.e. they were already united.

Another factor was the acquisition of Tanganyika after World war one, encouraged the British to make East Africa one state.

The British lacked manpower to administer the whole of East Africa.

Indirect rule was favourable and successful in all the three East African states.

The climatic conditions in East Africa were similar, so the administrators couldn't get climatic disturbances as they moved from place to place.

Cultural and linguistic similarities forced Britain to think that East Africans were one people e.g. both Kenya and Tanganyika spoke Kiswahili language, all states had-the Bantu and Luo tribes /speakers, shared the samelake Victoria and other aspects.

Britain wanted to cut down the cost of Administration by reducing the number of administrators. The success of the British-Boer union in South Africa favoured the idea of closer union of East Africa.

The attitude of East Africans towards closer union

Uganda

The feeling here was expressed largely by the leaders in Buganda. They were opposed to it from the start, fearing that it would threaten the special

Africans in Uganda were generally apprehensive of any move that might place them under the dominance of the settlers in Kenya. So sensitive were the Baganda about anything to do with federation that when many years later, in 1953, the Colonial Secretary made a reference to the possibility of an East African Federation, there was an immediate outcry that culminated in the deportation of the Kabaka.

Tanganyika

Here the most outspoken critic of federation was the Governor, Sir Donald Cameron.

He was particularly annoyed at the attempt made by the Governors of Kenya and Uganda in 1926 to stop the building of a rail link between Tabora and Mwanza, which would inevitably take away some of the trade and traffic that went through Uganda and Kenya.

Cameron even threatened to resign if the suggestion was put into effect. The British Government realised that its mandate in Tanganyika made it responsible for the League of Nations, and there could well be strong condemnation of any move seen to threaten the well - being of the African population. For these reasons opinion in Tanganyika was not in favour of closer union.

Kenya

At first most people opposed the scheme, including the settlers. African leaders feared that it would interfere with their demands for representation in the Legislative Council.

However, European feeling began to change, particularly after Lord Delamere had convened a meeting at Tukuyu in southern Tanganyika of settler representatives from East and Central Africa.

It was realised that there might be much to gain from the federation , provided they had a major voice in government and in its policies . The Kenya settlers became keen supporters of the idea, and were encouraged by the appointment of Sir Edward Grigg as Governor. He had been instructed by the British Government to prepare plans for a federal union.

In 1927, his committee on closer union reported that the scheme could be implemented , pointing out that the boundaries between the three territories were in any case artificial and that there would be much to gain by co-ordinating the resources of East Africa.

Change of policy to economic co-operation rather than federation

In spite of doubts and opposition from many quarters within East Africa the British Government pressed ahead with its ideas. In 1928 yet another survey was made, by the Hilton Young Commission; it came to the conclusion that while a complete political federation was not possible a High Commissioner for East Africa should be appointed with power to control the policies affecting the African population and to issue directives on certain matters to the three Governors. But this came to nothing and was not supported by the settlers.

After a number of further investigations and reports the idea of federation was finally dropped in the 1930s. However, it had been made clear that there was scope for much closer co-ordination in economic and social affairs, and it was along these lines that the Governors conferences developed.

From 1930 they met annually. Already in 1920 an East African Currency Board had been set up, and by 1930, railways, customs, defence, posts and telegraphs were shared, at least between Kenya and common system of tariffs and there was a move towards standardising policies on African taxation, elementary education, communications and industry. All these matters were dealt with by Government officials from the three territories.

Little communication between unofficials. During the Second World War there was a Joint Economic Council for East and Central Africa, with its own secretariat, to share the resources available and contribute to the war effort.

A number of other bodies were also set up to deal with supplies, research and development and refugees. Although this lasted only for the duration of the war it did give greater encouragement to the idea of some form of union.

THE FORMATION OF THE EAST AFRICAN HIGH COMMISSION

In 1945, the Colonial Secretary , Mr. Creech - Jones put forward proposals for the establishment of an East African High Commission. It was to have limited and defined powers and its functions would bring together all the services already shared on common.

There was strong feeling in East Africa about the racial composition of nay legislative body that might be set up as part of the organisation, and this affected the final proposals.

It was emphasised that this would not lead to a federation and that each territory would retain its existing forms of government. The East African High Commission came into beingin1948, with its headquarters in Nairobi.

The Commission consisted of the three Governors, together with an executive organisation headed by the Commissioner , and a legislative body with powers to make lawsaffecting the matters over which it had control.

The members of the legislature were to be chosen by the three countries on a racial basis, some being elected while others were nominated. The powers of the High Commission were limited.

It had no direct source of revenue and depended for its income in grants from each member state. It had no police force to its own, and no courts or laws on its own apart from the regulations mentioned above. Moreover its activities would depend on the unanimous support of the three Governors, any one of whom could exercise the power of veto.

In spite of these limitations the High Commission proved to be an effective and useful body, combining and co-ordinating a wide range of functions.

Why the East African federation failed

Several factors explain why the attempt to form a closer union of African territories failed; which were both internal and external.

First and for most, the political status of the three territories was not similar. Kenya was a colony, Uganda a British protectorate and Tanganyika was a British Mandate under the League of Nations.

Secondly in 1924 the idea of a federation was opposed by Uganda and Tanganyika governments they feared an increase of settlers in their countries. Africans rejected the idea fearing domination from the settlers.

Thirdly Africans generally disliked it because it was to benefit only colonialists Tanganyika governments, Britain and the settlers.

Fourthly still in Uganda in 1953 the Buganda government resisted strongly against the idea of the federation culminating in the Kabaka crisis of 1953.

Fifthly in Tanganyika the attitude of Sir Donald Cameroon towards the proposed closer union led it to fail. He was one of the most outspoken critics of the federation and yet he was a governor. He was annoyed by the governors of Kenya and Uganda's move to stop the building of a rail link between Tabora and Mwanza. Cameroon even threatened to resign this forced the British to drop the idea.

Furthermore in Kenya, the African leaders feared that it would interfere with their demands for representation on the legislative council. They had already been threatened by white domination of the affairs. Some Africans saw the attempt to a closer union as a stumbling block to their social and political institution. The death of Lord Delamare in 1931 deprived the Kenyan settlers of their influential spokesman. This vacuum was difficult to till and weakened the settlers' bargaining spirit.

Another factor is that the economic depression of 1931 led to a desperate economic situation in the three East African territories therefore the question of a closer union was allowed to drop as each territory devised independent means of improving her economy.

The successive commissions that were set up had failed to strongly recommend the idea of a closer union, for example that of Hilton Young proposed the establishment of a High Commissioner for East African territories but was not supported by the settlers.

The idea for the establishment of a closer union for the three East African territories originated from outside and not from within. Hence, it lacked strong popular support among the local population.

There was a change of government in Britain for example with the departure of Lord Armey from the colonial office the East African affair of federation was not enthusiastically followed up.

There was general opposition from Britain and France about formation of the federation. There was a feeling that Germany might regain control of Tanganyika. Hence, the public opinion did not favour the formation.

When the governors of Uganda and Kenya refused to build the railway to link Tabora and Mwanza, the governor of Tanganyika rejected the closer union idea.

Donald Cameroon the governor of Tanganyika was generally opposed to the idea of the union.

There was general fear that Germany might regain her control of Tanganyika.

The departure of the Lord Amery from the colonial office left the idea of the union without any follow up. The nearness of the World War I! disrupted the union idea since everybody was worried of World War Two. Tanganyika was merely a British mandated territory under the League of Nations, It 'could be with drawn any time:

In Kenya, Asians and African traders opposed it because it would undermine their commercial rights.

There were already leadership conflicts about who would be the federation leader/chairman.

Thus a major reason for the failure to federate is the developmental socialism which had made Tanzania increasingly impatient of economic factors over which she had inadequate jurisdiction. And so this was a case of socialism militating against pan-Africanism at the level of union in East Africa.

Another reason for the failure to federate at the time of independence (1960-4) was the varying party structure. At the time Tanganyika was a one-party state de jure while Uganda and Kenya had fluid party systems withno laws against the existence of opposition parties.

The problems of harmonizing party organizations and policies were considerable. The multi-party states had an additional problem. If there is more than one party in a country, and the ruling party wants to federate with another country, the opposition party could play on local micro-nationalism and arouse hostility towards thegoverning party for proposing 'a loss of the country's identity'.

It can thus be argued that Obote had to be much more circumspect and cautious about theissue of East African Federation than either Nyerere or Kenyatta.

At least until the middle of 1964 Obote had to be careful lest the opposition parties in Uganda succeeded in arousing local Uganda loyalties to pose a serious challenge to Obote's more pan-African inclinations. It was not simply a matter of personal jealousies between national leaders. The former Africa correspondent of The Times newspaper of London, W.P. Kirkman, wrote:

any arrangement which put Mr Kenyatta at the top (a position he would certainly get through age and prestige) and Mr Nyerere in second place (which he would have earned because he was the inspirer of the East African Federation) would leave Mr Obote of Uganda out in the cold.2

But Obote had to consider more than just his personal position. His overriding problem was that of taking the majority of his countrymen with him into federation, a task he did not feel he could accomplish at the time.

Lastly, when Kenya gained independence each nation developed differently. For example Kenya adopted the capitalist path of development Tanganyika took a socialist one while Uganda took more a less a middle path, thus a federation became impossible.

Achievements

Despite the failure of the union idea by 1940 it left behind the following achievements.

Firstly, a common currency for all the three states was established in 1920;

Secondly, railways were widely extended into all the three colonies;

Thirdly, common tariffs (taxes) were introduced across East Africa.

Fourthly, the East African high commission was established.

Furthermore, from 1930 Governors conferences were held annually.

Another achievement is that there was amalgamation of postal services, railways, customs, defence services etc.

Finally, a Plan to establish a central legislative assembly was put down in 1945

2 W.P. Kirkman, Unscrambling the Empire, Chatto and Windus, London, 1966. p. 135.

Licensed under the Developing Nations 2.0

A Complete East African History ebook