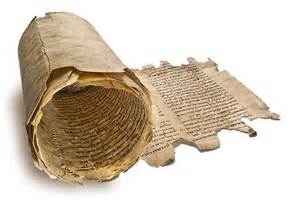

The Dead Sea scrolls

The finding of the

first of the Dead Sea scrolls in 1947 opened a new field of study which has

cast new light on Judaism until A.D. 70.

It has been possible to

find out a great deal about the life and beliefs of the Jewish monastic

community at Qumran which' was destroyed in about A.D. 68, obviously in the

Jewish war against the Romans. Amongst thousands of fragments of scrolls and a

number of complete ones, about five hundred separate writings have been

identified. Nearly every book of the Jewish Scriptures has been identified as

well as writings of the community itself, previously unknown to scholars. Two

of the most important of the community's writings are those known as the 'Rule

of Discipline' and the 'Rule of War'. It is clear from the writings of the

community that they believed they were living in the last days of the present

evil age and expected God to intervene dramatically in the events of history;

they waited for the coming of another great Davidic king. They followed a

strictly disciplined life, striving to maintain ritual purity, performing

frequent ritual washings, so that they would be ready for the Day of God's

imminent Judgement. They wrote commentaries on the Jewish Scriptures and from

these it is possible to see how they understood the Old Testament writings;

they interpreted them as a direct guide for their immediate life and situation.

From excavations carried out at the site of the monastery, it is clear that

there was a large complex of buildings and a water supply; between two or three

hundred people must have lived there. A writing-room (with ink wells still

preserved) and a pottery factory where large jars for storing scrolls were

made, have been identified. No scrolls were discovered on the site itself but

in nearby caves where the community hid them to protect them from the Romans.

In the desert of Qumran these intensely religious Jews waited for God's coming.

It was quickly noticed

by some scholars that in some of the writings from Qumran there is distinctive

language very similar to that used in some passages of John's gospel; for

example, phrases such as 'the sons of light', 'the light of life', 'walking in

darkness' are used, which remind us of the language not only of John's gospel

but also of the letters of John (1 John 1 :5-6, 2:9-11, and John 1 :4-9, 8 :12

and 12:46), The Qumran community thought of the world in which they lived as a

kind of battlefield between good and evil, truth and falsehood, light and

darkness, and this same understanding is found in the gospel and letters of

John, although in a specifically Christian context which is totally lacking in

the Qumran scrolls.

In assessing the

importance of the discoveries at Qumran to New Testament study, we can say that

they have greatly illuminated the Jewish background against which the ministry

of Jesus was carried out. We can understand better the intense religious

fervour of the Jews which, for example, made crowds come out into the desert

area (not so far from Qumran) to hear John the Baptist preach, and which

underlies the fanaticism of the Pharisees and the teachers of the Law. John the

Baptist, and then Jesus, preached at a time of intense religious expectation

which made people willing to come out and listen to travelling preachers and,

in the case of some, made them very concerned that they should be ready for

God's coming. The thought and language of communities such as that at Qumran

are likely to have spread amongst many devout Jews, which can explain why

phrases such as those just noted can occur in John's gospel. There is no

evidence that the writer of the gospel was in any way connected with such a

community but it is very likely that he used ideas which were circulating

amongst many Jews. We need to be clear that in the Dead Sea scrolls there is no

reference to Jesus or to specifically Christian beliefs; the community was

totally committed to its reformed kind of Judaism and no Christian influence

can be found in its writings. However, it was from such communities that the

challenge of repentance and reform was presented to the Jews of Palestine and

may have prepared some to listen to John the Baptist and Jesus.

Identification of

places in John's gospel, and historical setting

A number of places

unknown to the other gospels are mentioned in John's gospel. Archaeological

work has now enabled nearly all the places referred to in the gospel to be

identified. We may mention particularly the previously unknown pool of

Bethzatha or Bethesda with its five entrances, found near the site of the Temple

in Jerusalem (John 5:2); the great stone pavement (Gabbatha) where Pilate sat

when Jesus was brought to him, in the north-west corner of the Temple area (19:

13); the towns of Sychar (4:5), Aenon (John 3:23) and Cana (2:1). From the

identification of all the places named in John's gospel, it is clear that the

writer preserved authentic evidence about Jerusalem and southern Palestine in

particular. The historical setting of Jesus' ministry is seen to be authentic,

perhaps more than in the synoptic gospels. The writer refers to the mutual

hatred of Jews and Samaritans (4 :9, 8 :48), contempt for Galileans shown by

southern Jews (I :46, 7 :41), crowds looking for a Davidic Messiah (6: 15).

Pilgrimages to Jerusalem for the many Jewish Festivals (5: I, 7: 10, 10:22,

11:55, 12:20), the unfinished Temple building project of Herod and his sons

(2:20), the separateness of the Pharisees (7:49), Roman rule (II :48, 18 :28,

19: 12-22).