Political parties,elites ansd sub-elites

African political associations in the generation before the Second. World War, especially in West Africa, were dominated by a Western-educated elite of bourgeois intellectuals, a professional class of lawyers, doctors, teachers and Journalists, seeking greater status within a reformed colonialism. This small but growing elite pressed on colonial governments the demands of the elite class: increased African representation in legislative and local government councils, better opportunities in government service, and increased educational facilities.

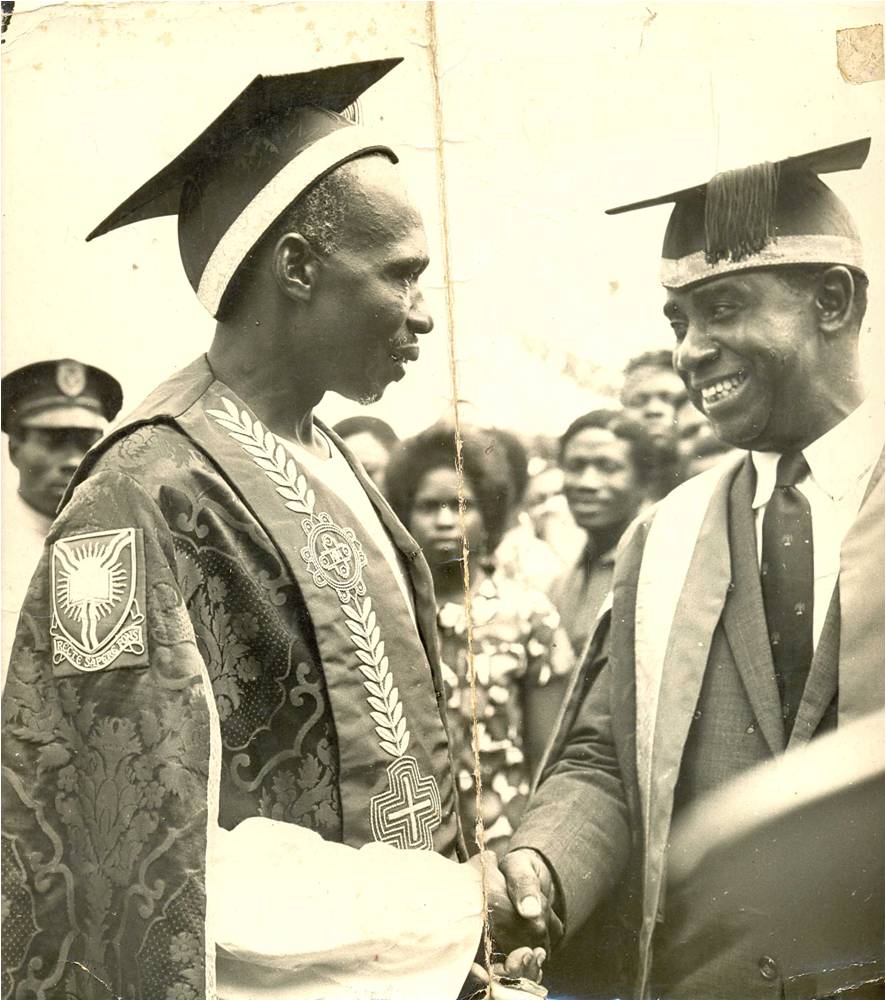

East African elite politicians ranging from Nyerere, Obote, Kenyatta and Odinga: Western-educated elite of bourgeois intellectuals, a professional class of lawyers, doctors, teachers and Journalists, seeking greater status within a reformed colonialism

These demands were more commonly made in British territories. In the French colonies the elite was more concerned with pressing for abolition of the hated indigenat status and for a widening of the opportunities to qualify for citizenship. John Hatch has argued that "The pre-war intelligentsia were still too self-conscious of their new social status to feel any affinity with illiterate masses. They sought personal acceptance, even if it were merely acceptance as critics within the system.''

The economic and social changes of the Second World War and the expectations of political change aroused by the war, had the effect of transforming the pre-war elite political associations into more broadly based and more radical political parties. The new parties recruited from the urban proletariat of new town dwellers and ex-servicemen and from the rural peasantry, as well as from the elite.

Sir Abubaker Tafawa Balewa as University Chancellor in Nigeria

The parties tended to be led at the national level by the elite and at the local level by a sub-elite. The period after the war saw the emergence of a provincial town and rural sub-elite, a petty bourgeoisie of poorly-paid teachers, clerks in local administration, pastors in mission or independent African Churches, more prosperous farmers and traders. Ex-teachers were prominent in the new parties because teachers in government schools were, as civil servants, generally subject to dismissal for involvement in political activities.

To the demands of the professional or bourgeois elite the parties now added the grievances of the local sub-elites. These local grievances centred on the barriers to African economic progress presented by Asian shopkeepers (Lebanese and Syrians in West Africa and Indo-Pakistanis in East Africa) and by European and Asian control of marketing of, crops. Moreover, African farmers and traders had little opportunity within existing local government systems to promote their own interests against those of non-Africans.

Nkrumah with Houpheit Boigny of Ivory Coast

Existing local economic grievances were exacerbated in British territories by Britain's post- war colonial economic policy. The war and its aftermath led to food rationing in Britain and to a programme of increased food production in the colonies. At the local level in the colonies government chiefs found themselves being forced to implement accelerated agricultural improvement schemes, by compulsion if necessary. Compulsion led to growing alienation of the rural peasant masses as a whole, and made it much easier for the national elite and local sub-elite to recruit mass support for the new political parties.

JARAMOGI OGINGA ODINGA: PROGRESSIVE NATIONALIST, PAN-AFRICANIST AND "THE DOYEN OF KENYAN OPPOSITION POLITICS"

The local sub-elite formed a vital link between the rural masses and the national elite. The sub-elite was linked directly with the non-Westernized masses by family ties and by land use, since teachers and traders were also farmers. To date, very little of the research into African nationalist politics at local level in the post-war period has been published. One of the few detailed studies of this kind is E.S. Atieno-Odhiambo's study of Oginga Odinga's Luo Thrift and Trading Corporation (LUTATCO), between 1945 and 1956. 2 Odinga as a politician, in and around the western Kenya lakeside town of Kisumu in Nyanza Province, gained his initial support from LUTATCO shareholders, who also backed him in his role as leader in Nyanza of Jomo Kenyatta's Kenya African Union (KAU). The LUTATCO men were typical of the local elite in post-war Africa south of the Sahara. To quote Atieno-Odhiambo:

Who were 'the people' in the context of Odinga's leadership in the years between 1945 and 1956? They were the new men, the 310 traders among whom could be counted masons, shopkeepers, tailors, cobblers and hoteliers, the 610 urban workers who were employed both in government organizations and private industries, the 50 teachers, 23 administrators, 49 minors, and 143 peasants, farmers, 'ladies' and 'gentlemen'. The 'masses' in this context were thus not really the peasants but the cadre above the peasant.

The local sub-elite played a vital role as middle-cadre communicators between peasants and the professional elite and cemented the alliance of social classes in the new political parties, and-thus made possible the mass organization of these parties.

National Movements and New States in Africa