From Gold coast to Ghana: mass nationalism versus elitist nationalism,and nationalism vdersus sub-nationalism

The

Convention People's Party (CPP) was a nationalist party for all the people of

Ghana and transcended both social class division and ethnic rivalries. At this

point we should look more closely at the victory of the CPP as a mass nationalist

party over the elite-led United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC), and at the CPP

victory over the ethnically based National Liberation Movement (NLM), Northern

People's Party (NPP) and Togoland Congress Party (TCP).

Nkrumah,

first as General Secretary of the UGCC and then as leader of the CPP, carried

out an organizational revolution in setting up a mass party in the Gold Coast,

Aided by his brilliant lieutenants Kojo Botsio and K.A. Gbedemah, Nkrumah led a

recruitment drive for new party members among the lower-level elite of Junior

civil servants, teachers and small farmers as well as among the masses of urban

workers and unemployed school- leavers. New branches were set up throughout the

country (though few recruits were made in the north) and firmly linked to a

strong central party organization in Accra.

The

professional and commercial elite that led the UGCC had hoped to replace

colonial rule by its own. The CPP upset these elitist calculations and carried

out political revolution based on radical social change. The CPP adopted a new

strategy and new tactics.

The

strategy was 'Self Government Now'. The tactics were 'Positive Action',

non-violent resistance on the Gandhian model for general Gandhian influence on

English-speaking African nationalists). Positive Action took various forms: a

month's boycott against high prices charged by European and Syrian traders;

mass rallies; the general strike that led to the State of Emergency of January

1950. The CPP-was closely linked to the Trade Union Congress (TUC). One of the

more significant results of the February 1951 election was the defeat in his

own state of Sir Taibu Darku IX, leader of the Joint Provincial Council of

Chiefs, by Pobee Biney, leader of the TUC, an ex-serviceman and a railway

engine-driver. Biney's victory symbolized dramatically the triumph of mass

nationalism over elitist nationalism.

As

a mass party the CPP was far more ready than the UGCC to undertake the battle

for economic and social development (as well as the struggle for political

independence). Even before the CPP came to power in 1951 the party organization

was geared towards an attack on swollen shoot disease in cocoa trees. Party

workers educated farmers on the need to destroy infected trees even before

Nkrumah became Leader of Government Business.

What

was the nature of the ethnic opposition to the CPP in the 1950s and how did

Nkrumah and his party overcome this opposition? At first glance it might seem

that the task facing Nkrumah of building one nation out of ethnic groups in

Ghana was much easier than the same task facing nationalist leaders in other

African countries. This is because in Ghana the Akan-speaking people comprise

the majority of the population.

The

Akan include the Fante of the coastal region and the Asante further north; they

lived in all three administrative regions into which the colonialists divided

Ghana; and they never formed a political bloc against the non-Akan. There was

no Akan sub-nationalism to become a barrier to the growth of Ghanaian nationalism.

On

the other hand, in the 1950s powerful opposition to the CPP developed both

among the non-Akan peoples of the north and east (especially the Ewe cast of

the Volta River) and in the Asante branch of Akan-speakers. CPP mass

nationalism routed UGCC elite nationalism in the 1951 election but now faced a

new challenge from a loose coalition of regionally based sub- nationalisms in

the run up to independence in 1957 and in the first few years afterwards. In the elections of June 1954 the CPP,

largely as a result of its considerable achievements in government since 1951,

won 72 out of 104 seats. However, the CPP was opposed at these elections by

seven other parties. Of these, the strongest was the Northern People's Party

(NPP), founded in April 1954, and drawing its support mainly from conservative

non-Akan northern chiefs.

The

NPP's battle cries were 'the white imperialist must not be replaced by the

black and the North for northerners'. The leaders of the party were chiefs like

S. D. Dombo, Yakubu Tali. J. A. Braimah and Mumuni Bawumia. The NPP won

regional support among the Gonja, Dagomba, Mamprussi and other northern ethnic

groups. The NPP won 12 out of the 26 northern seats in 1954. In close alliance

with the NPP was the Muslim Association Party (MAP), which sought support among

the Muslims living in the main towns. MAP won one seat in 1954.

The

Togoland Congress was formed among the Ewe people east of the Volta to fight

for the unification of the British and French mandated territories of Togoland,

administered as part of the Gold Coast and French Togo respectively. The

Congress was a pan-Ewe movement. The TC won three seats in 1954. However, in

the UN-sponsored referendum of 1956 the majority of Togoland voters, most of

whom were non-Ewe, voted for union with Ghana.

The

most serious threat to CPP dominance and to a Ghana-wide patriotic nationalism

was the rise of the National Liberation Movement (NLM) formed after the 1954

election. The NLM was an Asante regional party based on local Asante grievances

at CPP government and party decisions. First, the Asante felt slighted when the

1953 Electoral Commission recommended an increase of only two seats in Asante,

in contrast with much larger additions of new seats in other parts of the

country.

The

Asante felt humiliated and angry when the CPP government accepted the

Commission report. Secondly, a group of Asante Youth Association members who

failed to be nominated as CPP candidates in 1954 left the CPP to form the NLM.

Thirdly, Asante cocoa farmers were highly discontented when the government

fixed the cocoa price at £3. 12 instead of the promised £5.

The

NLM received official support from both the Kumasi stare council and the

Asante- man Council, a development of great significance because the influence

of the chiefs was still very great in the rural areas in Asante. The NLM

pressed for a federal constitution. Violence between NLM and CPP supporters was

widespread and persistent in Asante from 1954 to 1956. Some people were killed

and many houses were damaged or destroyed. During this period neither Nkrumah

nor any of his Cabinet Ministers could set foot in Kumasi, Asante's capital.

The

NLM allied with the other regional opposition parties - the NPP, the TC and the

MAP - in the pre-independence election of July 1956. Dr Kofi Busia, a

university sociologist, was chosen as parliamentary leader of this electoral

coalition. Yet the CPP won 71 out of 104 seats. The NLM won none of the 44

seats in southern Ghana from Nzimaland in the west to Accra in the east.

The

CPP won about half the seats in each of the other areas of the country,

including even Asante where it won nine seats to the NLM's twelve. Nearly all

the constituencies of the Bono people (northern Asante) voted solidly for the

CPP, out of fear of a revival of the ancient Asante imperial power. The CPP

were able to exploit feuds between Asante chiefs to win some seats in

metropolitan Asante itself.

The

opposition parties in 1956 performed rather better than the number of seats

they won might suggest. They polled as many as 299 000 votes against 398 000

for the CPP.

Nkrumah

was acutely aware of the regionalist threat to CPP rule. However, he was unable

to work with the opposition parties and strive more towards a political

accommodation with them in the interests of greater national unity, for a

combination of reasons.

First,

the NLM and NPC were class-based as much as ethnic-based and their generally

conservative and/or chiefly leaders could not tolerate Nkrumah's radicalism and

socialist ideology.

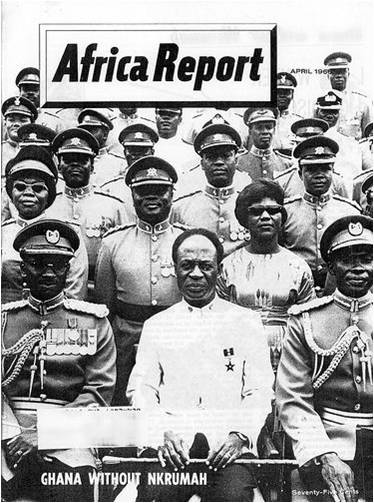

Secondly,

Nkrumah became increasingly dictatorial after independence, and preferred to

deal with the NLM largely by undemocratic means.

His

government suspended the NLM dominated Kumasi Municipal Council, dismissed

anti-CPP chiefs and introduced the Preventive Detention Act in July 1958 in

order to facilitate the arrest of the leaders of the United Party (formed in

195 7 out of the NLM, NPC and other regional parties) later in the same year.

Nkrumah seriously weakened ethnic opposition to the CPP government, but he did

so by undemocratic means rather than by revitalizing the now complacent CPP.

He thus set himself on the road to a fun-blown dictatorship which ultimately led to the broadening of opposition from an ethnic base to a nationwide phenomenon. By uniting all sections of the population against himself by his domestic excesses between 1958 and 1966, Nkrumah overcame local sub-nationalisms in Ghana in a way he had not intended.

National Movements and New States in Africa