Introduction

POLITICAL PARTIES, NATIONALISM AND ETHNIC SUB-NATIONALISM

A political party is a group of people who hold common ideas on how state power should be organized. It can also be defined as a group of people who are organized with a purpose of achieving and exercising political power by electoral or other means within a state.

According to Moses Wamanga, there are four characteristics, which usually distinguish parties from other groups: Parties aim at exercising Government power by winning political office. Parties are organized bodies with formal "card carrying" membership. Parties typically adopt a broad issue focus, addressing each of the major focus of government policy. There should be a general ideological identity.

There have been two kinds of political nationalism in Africa during the struggle for political independence since 1945. First, there has been the ethnic sub-nationalism of a community speaking one language.

Secondly, there has been multi-ethnic nationalism, where men and women of different ethnic sub-nations have striven together to develop a feeling of patriotism, or love for their political country, and to build one political nation out of numerous ethnic groups.

It is important for the purposes of this chapter to examine the successes and failures of nationalist political parties in trying to develop a broader multi-ethnic or non-ethnic national consciousness rather than develop ethnic sub- national consciousness during the struggle for political independence (broadly in the period from 1945 to 1964).

Patrice Lumumba

What are the origins of the ethnic sub-nationalism that political parties either battled' against or embraced after 1945? Does this sub-nationalism predate the colonial period in Africa? Was its development encouraged by colonial rulers? Nationalism was a strong feature of African civilization in the pre-colonial period. Colonial rule in general had the twin effects of weakening nationalism and encouraging ethnic sub-nationalism. This may at first glance seem to be refuted by the simple observation that most of Africa's new political nations have grown out of the colonial embryo.

After all, the boundaries established in European chancelleries to delineate colonial territories during the Scramble for Africa have in almost all cases remained intact into the last quarter of the twentieth century. This does not mean, however, that the, creation of nations in Africa can be attributed to the colonialists. Indeed, the colonialists destroyed many African political nations in the process of establishing their own political pattern in Africa. Large empires like those of the Tokolor, Mandinka and Fulani were split up between several colonial territories.

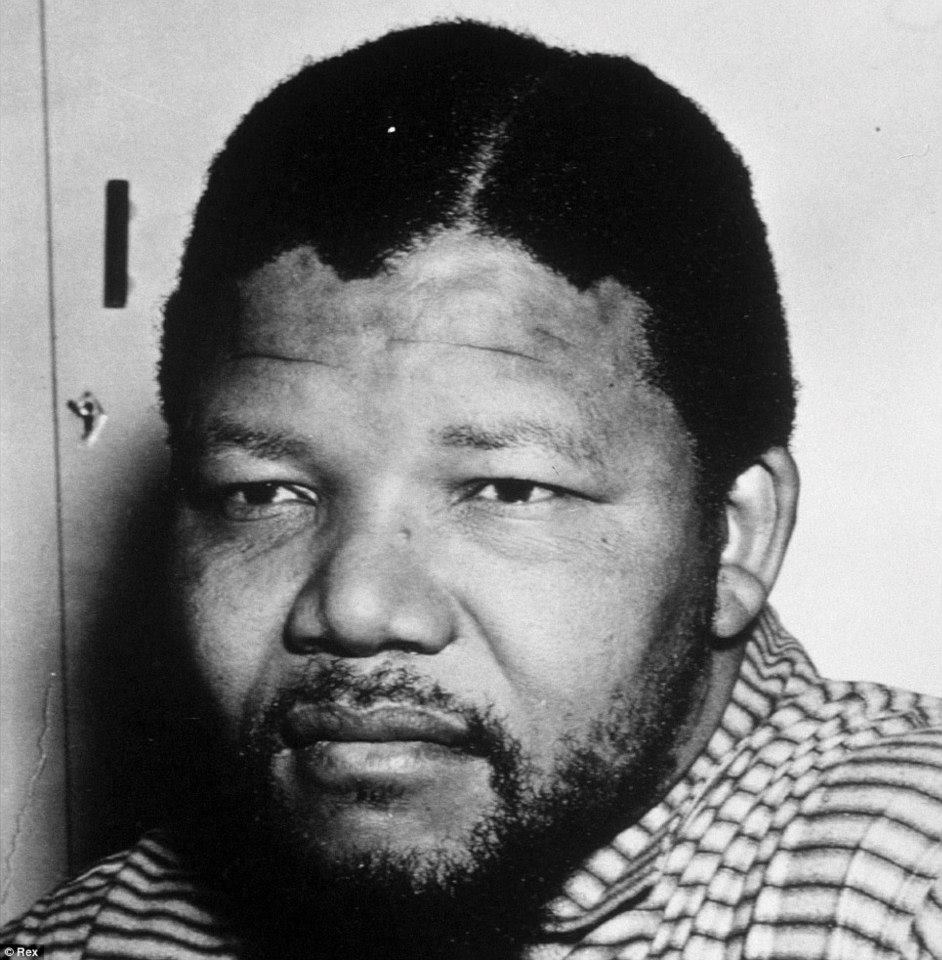

Nelson Mandela, founded the ANC

The independence of smaller nations like that of the Zulu was submerged within a single colonial territory. Several African states which fell victim to colonialism managed to re-emerge in the post-colonial era with substantially their pre-colonial boundaries, hardly affected by the redrawing of the political map of Africa by Europeans. These states were Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, the Sudan, Dahomey, Madagascar, Swaziland and Lesotho. Two pre-colonial states - Ethiopia and Liberia - even managed to survive the Scramble for Africa.

The remaining thirty or so new African political nations are commonly supposed to be conglomerations of mainly 'stateless' societies and small states, lumped together fortuitously by colonial map-makers. For example, Uganda was created as a colonial territory our of four Bantu kingdoms and dozens of smaller Bantu and Nilotic 'stateless' communities. We should not assume from this, however, that most pre-colonial Africans lived outside 'nations' or "states' in "stateless societies'.

Typically nineteenth-century European definitions of nationality based on European political norms of nations with centralized governments and fixed boundaries do not and need not apply to Africa. Politically decentralized nations consisting of ethnic groups which lacked political unity and central political institutions were often united by a common language and culture.

Examples are the pre-colonial Kikuyu, Nandi and Luo societies in Kenya. In fact, if we define politically decentralized but culturally united societies like these as cultural nations (as distinct horn political nations) clearly far more African communities than commonly imagined have inherited a national tradition and a national consciousness from their pre-colonial past.

The colonial rulers joined together many ethnic nations in a single territory. Sometimes political-cultural nations, like the Fulani-Hausa of Northern Nigeria, were united with more purely cultural nations like the Ibo of Eastern Nigeria, within a single new country. This amalgamation of peoples by political geography did not, however, in itself produce multi-ethnic nationalism. In general, colonial rulers attempted to govern by dividing the African peoples and encouraging expressions of regionalist and ethnic feeling and practice.

The colonial tactic of 'divide and rule' was used within individual colonies in order to play off one potential or actual source of opposition against another. As we saw in previous chapters, the British did not favour balkanization and gave strong support to federations, as in Central Africa. But the British did support ethnically based political parties as a tactic to weaken and divide nationalist opposition to colonial rule at the local, territorial level. Several examples of this ethnic political party rivalry will emerge in the course of this chapter, notably in English-speaking West Africa, in Uganda and (for a time) in Kenya and Zambia.

One factor which encouraged ethnic sub-nationalism in the decolonization process was British eagerness to export to Africa their particular version of parliamentary government, with several parties and a recognized opposition. In practice this development led to the emergence of numerous ethnically based parties in opposition to other ethnic parties.

Nyerere's famous reply to a Governor of Tanganyika, 'How can I create an opposition to myself?', was prompted by the Governor's failure to grasp that Nyerere had forged such a strong non-ethnic party that the various African communities or language groups of Tanganyika were united under the TANU umbrella and therefore the question of an opposition (almost inevitably ethnic if the pattern of other colonies was adopted) could scarcely arise in the Tanganyikan situation.

National Movements and New States in Africa