The Revolution Of 1952

Revolution Starts

The origins of the Egyptian army takeover of July 1952 lay in the long British domination of Egypt and the inability of the Egyptian monarchy to end British domination. Britain - had occupied Egypt in 1882 in order to collect debts by Egyptians to European financiers and to ensure the security of Suez Canal communications between Britain and British India.

In spite of the British occupation, Egypt remained nominally a Turkish province, until the First World War when it became a British Protectorate in name as well as in fact.

The 1936 Anglo-Egyptian Agreement ended Britain's military occupation of the heart of the country, but allowed Britain to retain the right to station troops in the Suez Canal Zone. In the Second World War Egypt sunk to the level of a British military base and Cairo became the headquarters of the British Eighth Army fighting the Afrika Korps of the brilliant German General Rommel.

Egyptian

resentment of British domination reached, its height in 1942 when Rommel's

advance from the western desert towards the lower Nile encouraged pro-Axis

sentiment. Rommel offered to the Egyptians a chance to break the stranglehold

Britain had had over their country for 60 years - though it is doubtful if they

weighed accurately the disadvantages of a German rather than a British

occupation during the Nazi era. Anwar al-Sadat, a revolutionary young army

officer, actually made contact with Rommel's headquarters; but this was

discovered and Sadat spent the rest of the war in a British prison camp.

Egyptian

resentment of British domination reached, its height in 1942 when Rommel's

advance from the western desert towards the lower Nile encouraged pro-Axis

sentiment. Rommel offered to the Egyptians a chance to break the stranglehold

Britain had had over their country for 60 years - though it is doubtful if they

weighed accurately the disadvantages of a German rather than a British

occupation during the Nazi era. Anwar al-Sadat, a revolutionary young army

officer, actually made contact with Rommel's headquarters; but this was

discovered and Sadat spent the rest of the war in a British prison camp.

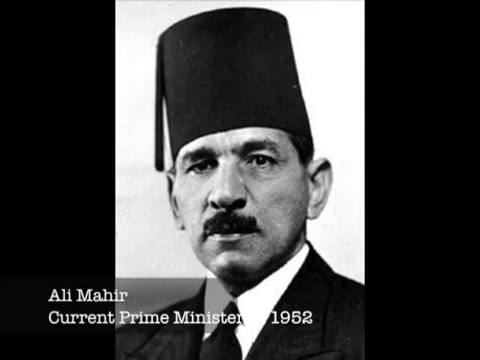

British tanks surrounded King Farouk's palace and forced him to appoint as Prime Minister not the favoured candidate, the pro-Axis and popular Ali Maher, but the pro-British leader of the Wafd nationalist party, Nahas Pasha. Besides, the British defeated Rommel at El Alamein.

The

post-war period from 1945 was marked by rampant corruption and conspicuous

spending by King Farouk and his family and by the Wafd leaders. The Wafd had

come to represent the wealthy families of Egypt and did nothing to reduce the

gap between the rich and the poor in the country. If anything, the post-war

Wafd governments widened the existing gap in wealth between the class of large

landowners and the fellahin (peasants owning tiny smallholdings or no land at

all).

The

post-war period from 1945 was marked by rampant corruption and conspicuous

spending by King Farouk and his family and by the Wafd leaders. The Wafd had

come to represent the wealthy families of Egypt and did nothing to reduce the

gap between the rich and the poor in the country. If anything, the post-war

Wafd governments widened the existing gap in wealth between the class of large

landowners and the fellahin (peasants owning tiny smallholdings or no land at

all).

After 1945 more and more fellahin found themselves unable to make a living for themselves and to feed their families by cultivating their own land. Many sold up to large landowners and went to work for the latter on their larger estates. By 1952 as few as 6 per cent of Egypt's landowners owned as much as 65 per cent of the cultivated area.

Growing

opposition to Farouk's regime was spearheaded by the radical nationalist but

traditionalist Muslim Brotherhood led by Sheikh Hassan el-Banna, and by the

radical nationalist but modernist Free Officers, a group of secret conspirators

in the army increasingly under the control of the cool-headed Nasser rather

than the impetuous Sadat. The Free Officers were determined to effect a

revolution after the Egyptian army was badly let down by the government in the

Palestine War of 1948-9, when Egypt fought alongside other Arab states in a

vain attempt to destroy the newly-created state of Israel.

Growing

opposition to Farouk's regime was spearheaded by the radical nationalist but

traditionalist Muslim Brotherhood led by Sheikh Hassan el-Banna, and by the

radical nationalist but modernist Free Officers, a group of secret conspirators

in the army increasingly under the control of the cool-headed Nasser rather

than the impetuous Sadat. The Free Officers were determined to effect a

revolution after the Egyptian army was badly let down by the government in the

Palestine War of 1948-9, when Egypt fought alongside other Arab states in a

vain attempt to destroy the newly-created state of Israel.

ANWAR SADAT, his peace with Israel engendered his assassination.

The Free Officers fought bravely. Some were killed and many were wounded. Major Nasser survived a bullet close to the heart, and distinguished himself by leading a skilful counter- attack in the Faluga pocket 20 miles north-east of Gaza, thus preventing the Israelis over-running Faluga.

But the Free Officers could never forgive the political and administrative incompetence of the government which supplied them with outdated arms and only irregularly with food and military supplies. Colonel Ahmed Abdul Aziz before he was killed reminded his colleagues, 'Remember that the real battle is in Egypt.'

After the Palestine debacle the Wafd government tried desperately to win popularity at home by pursuing an anti-British policy. In October 1951 Nahas announced the unilateral abrogation of the 1936 treaty. British forces in the Canal Zone were subjected to guerilla attacks and sabotage and their food supplies were cut off. Neither Nahas nor the Egyptian people seriously expected these measures would lead to a British evacuation of the canal. When the British responded by the assault on the police headquarters in the city of Ismailia on 25 January 1952, which left 43 policemen dead, the Egyptian public blamed their government for defeat and the throwing away of lives.

After

riots in Cairo Nahas was dismissed by Farouk and replaced at last by Ali Maher.

But it was too late to shore up the ramshackle structure of Farouk's regime.

The Free Officers, led by Nasser, were ready to move.

After

riots in Cairo Nahas was dismissed by Farouk and replaced at last by Ali Maher.

But it was too late to shore up the ramshackle structure of Farouk's regime.

The Free Officers, led by Nasser, were ready to move.

National Movements and New States in Africa