Influence of Independence of French Guinea in 1958

Not only that the independence of French Guinea in 1958 effectively helped to shape nationalist politics in countries still under colonial regime in Africa. The French leader, De Gaulle, put in place a referendum in 1958 requiring French colonies in West and Equatoria Africa to vote no' for independence or yes' to continue with association with France. All French colonies except Guinea voted no to continue to depend on France.

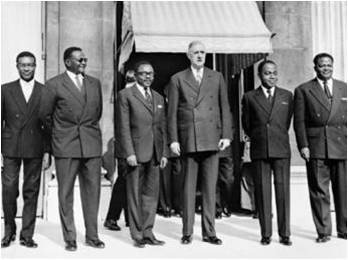

Charles de Gaulle et les présidents africains (de g. à dr.): Philippe

Yace (président du parlement de Côte d’Ivoire), Hamani Diori (Niger), Maurice

Yameogo (Haute-Volta), Félix Houphouët-Boigny (Côte d’Ivoire), Hubert Maga

(Dahomey), à l’Elysée le 08 mars 1961. (AFP

Charles de Gaulle et les présidents africains (de g. à dr.): Philippe

Yace (président du parlement de Côte d’Ivoire), Hamani Diori (Niger), Maurice

Yameogo (Haute-Volta), Félix Houphouët-Boigny (Côte d’Ivoire), Hubert Maga

(Dahomey), à l’Elysée le 08 mars 1961. (AFP

Sekou Toure came to the opposite conclusion that France was the main cause of lack of freedom and dignity in West Africa, and so, he led French Guinea to vote 'no' for Guinea's independence. The effects of Sekou Toure's no vote in De Gaulle referendum was tremendous. French-Guinea became independent abruptly.

François Mitterrand Presidents of France and

Felix Houphouet-Boigny (right)

France got annoyed and French technicians and administrators were ordered to leave immediately. French financial aid Guinea was cut off. But Guinea did not collapse because Ghana and other communist countries provided financial aid to her. Its impact on African political consciousness was big.

In British West Africa, Sekou Toure's 'no' vote was received with shocked disbelief. To English West Africa, Toure was the only African nationalists who could be put on equal footing with their own nationalist leaders such as Kwame Nkrumah.

Guinea's brave declaration of independence mobilised opinion in every colony in favour of independence. It convinced Senghor of Senegal, Houphouet Boigny of Ivory Coast and also the French that independence for French Africa was inevitable i.e. could not be resisted anymore.

Sekou Toure became so popular and this was a serious threat to all political leaders who had either to follow his example or be eclipsed. Therefore, in 1959, Senegal and Sudan (Mali) formed the Mali Federation in order to be strong enough to confront French power within the community. The federation soon requested for an amendment of the constitution which could allow members remain in the French community even after gaining full independence. France accepted.

As a result, the remaining seven states i.e. Senegal, Sudan (Mali Federation), Ivory Coast-, Dahomey. Niger, Upper Volta and Mauritania became independent in 1960. Hence, Sekou Toure's *no' vote was very instrumental in luring other remaining members of the French federation to seek for their independence as soon as possible.

And once the remaining seven states achieved their independence following guinea's example, the French federation of West Africa broke down. (i.e. Guinea's 'no' vote shattered the plan for a well- ordered France-African community).

By demonstrating the practicability of guinea's survival after gaining independence even when France had withdrawn all her support, Sekou Toure provided African nationalists in many other parts of the continent the lesson they took deeply to heart. This lesson was most taken in British Central Africa especially in southern Rhodesia where political parties began to be formed to lead Rhodesian nationalism.

The emancipating of the French Guinea and later other territories within the French Federation in West and Equatorial African gave a big boost to independence a struggles in Belgian Congo made Belgium to think quickly and grant independence to the nationalists in 1960.

GENERAL CHARLES DE GAULLE, visited the colonies,

offering them the choice of pulling out from the French embrace, or joining

with France in the creation of a new French Community.

GENERAL CHARLES DE GAULLE, visited the colonies,

offering them the choice of pulling out from the French embrace, or joining

with France in the creation of a new French Community.

Upon gaining self-determination, French Guinea provided practical support to PAIGC, a liberation movement that was fighting the Portuguese imperialism in Guinea - Bissau and Cape Verde Islands. It provided it with moral support and with a base.

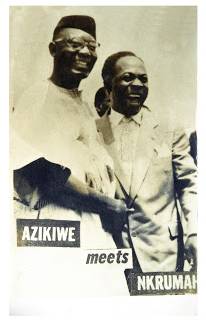

Guinea started to follow the policy of radical Pan-Africanism. Together with Kwame Nkrumah, Sekou Toure opposed division of Africa into smaller and weaker states. Hence, to demonstrate their seriousness, they created the Ghana-Guinea Union in 1958. to which Mali was added in 1961. Through creating this union, Sekou Toure, Kwame Nkrumah and Modibo Keita kept the fires of Pan Africanism alive at the crucial time when unity was difficult to achieve in Africa. Even when Nkrumah was toppled by the army in 1966, he was received in Guinea Republic as a co-president by Sekou Toure.

Nkrumah realized that what Sekou Toure needed above all else in that initial shock was, at least, a morale-booster; he needed to know he had friends. Nkrumah promptly made a grant of financial support to Guinea to tide her over during that initial period of independence. It was a move worthy of the head of government of the first black African country south of the Sahara to win independence from colonialism. It was a move worthy of a true son of Africa- Nkrumah made available to Guinea a Ghanaian loan of f4 500 000, and the two countries planned closer association.

Two months later Ghana and the Republic of Guinea look another step forward, by making formal moves to unite. They described their union as a nucleus for a Union of African States. They also envisaged it, in effect, as an alternative to de Gaulle's vision of a French Community. This would be an African association to rival the ties that France was forging with her former colonies.

In fact, formal independence for the French colonies came sooner than many people expected. After the referendum and the vote to remain under France, some people assumed that the colonies would remain colonies indefinitely. But De Gaulle's vision soon allowed for the granting of formal political sovereignty to the colonies, though with the retention of close economic and cultural ties with France.

Even after the 1958 Referendum there was strong general support in French West Africa for Federation instead of Balkanization. Countries like Senegal and Soudan had voted 'Yes' in the hope of achieving Federation within the French Community, and because they were not prepared to reject French aid. On 29-30 December 1958, federalists from Senegal, Soudan (Mali), Upper Volta and Dahomey met at Bamako and convened a constituent assembly, which met in Dakar in January 1959. A constitution for a proposed federation of Mali was drawn up, but in the following referendum only Senegal and Soudan voted 'Yes'. France and Ivory Coast, which saw the continued balkanization of West Africa as their only hope of maintaining the French Community, managed between them to exert pressure on Upper Volta and Dahomey not to join the Mali Federation. Upper Volta was coerced by economic threats from Houphouet to cut off Upper Volta from the sea and by France whose army pensions were a vital source of income in Upper Volta. Moreover, the French High Commissioner Maission exploited the regional differences between Upper Volta and Ivory Coast. Dahomey was coerced by the threat of withdrawal of French finance for a projected deep-water port at Cotonou; though it is also true that fear of domination by distant Dakar played a role in influencing the Dahomeyan decision not to federate.

When Houphouet helped to detach Upper Volta from the proposed Mali Federation, he did not intend that poor Upper Volta should link with rich Ivory Coast and live off it.

He wanted a strong French Community in which Upper Volta would live off France. But even Houphouet was forced by events to turn to federalism, though in a mild form. In order to prevent Senghor dominating French-speaking West Africa, -Houphouet formed the Sahel-Benin Union, made up of Ivory Coast. Upper Volta, Dahomey and Niger.

The Union was more of an entente than a formal federation. Indeed the Union was generally called the entente. There was no federal assembly, only a council of prime ministers and delegates. In any case, Houphouet's new pseudo-federal policy collapsed when France decided to grant independence to states outside the entente without either excluding them from membership of the Community or denying them economic aid, as had happened to Guinea.

Senegal and Soudan were granted independence as the Mali Federation which soon collapsed and the UN Trust Territories of Togoland and Cameroon also became politically independent. The entente states realized they could gain nothing further by continued dependent status than they could gain as sovereign states. In June I960 they separately requested independence and achieved it in August. Thus territorialism, or balkanization, had triumphed over federalism in French West Africa.

National Movements and New States in Africa