British East Africa: Closer Union and the High Commission

The East African High Commission

This was set up in the colonial period as a first step towards the economic unity of the three British territories of Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyika, was transformed on the eve of independence into a more integrated Common Services Authority, but Just failed to be developed into a fully-fledged political federation.

The origins of British plans for closer union between its East African territories are found in the period after the First World War. Colonial secretaries and governors favoured closer union for the sake of economic development. Indeed common services between Kenya and Uganda for railways, customs, defence, posts and telegraphs were started in the 1890s.

After 1918 these services were extended. In the 1920s and 30s Kenya's European settlers became strong advocates of the political union of British-ruled East Africa, partly because they hoped the area of their settlement could be extended into the highlands of Uganda and Tanganyika, and partly because they believed that the fuller integration of Tanganyika with its northern neighbours would make German demands for the return of Tanganyika less effective.

Furthermore, they hoped a settler-ruled stare on Southern Rhodesian lines could be set up in East Africa. However, successive British governments maintained their commitments to develop the East African colonies as African countries. The Kenya settlers failed to attain political power in Kenya, lei alone in East Africa. The Baganda, hitherto powerful allies of the British in Uganda, led African opposition to the settler plan for closer union and a vast while-dominated federation.

Successful co-ordination between the three territories in the Second World War in matters such as war supplies and refugees encouraged the post-war Labour government to set up the East African High Commission, which came into operation on I January 1948.

The EAHC was composed of the Governors of Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyika, an Assembly in which Europeans were over-represented, and a regional civil service of expatriates. The Central Legislative Assembly was made up of seven High Commission officials, 15 territorial members (five from each territory, made up of one official, an African, an Asian and a European - all appointed, and a member elected by the territorial Legislative Council) and one appointed Arab member. The Commission's legislative powers covered customs, income tax, defence, railways and harbours, civil aviation, posts and telecommunications, and Makerere College in Kampala.

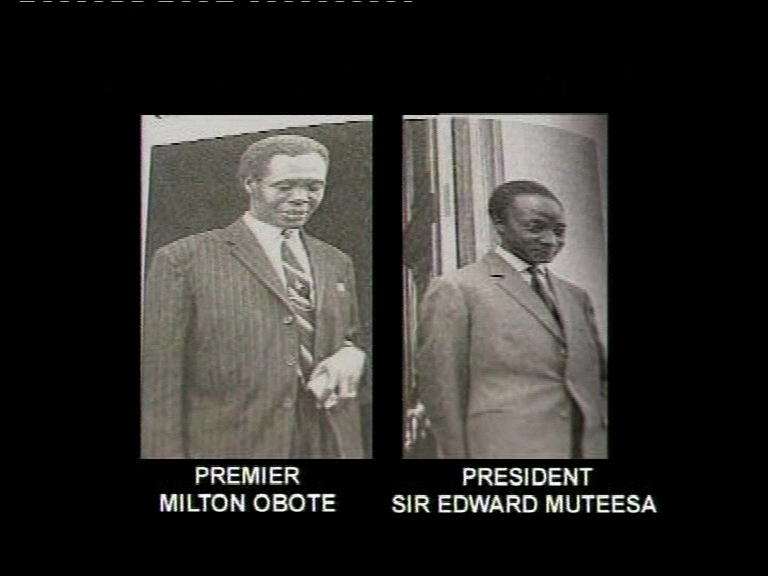

MILTON OBOTE had to be

much more circumspect and cautious about the issue of East African

Federation than either Nyerere or Kenyatta

The EAHC was not, however, a federation. The territorial governments retained major political and administrative powers including those over justice and police, health, housing, most education; labour and agriculture. Much of the Commission's revenue came from the territorial governments. The Commission's existence was subject to periodic review by the territorial legislatures. Each territory (in practice the Governor) could veto any executive decision of the Commission.

The EAHC was transformed because of the political changes in East Africa, such as the approach of independence and the emergence of unofficial and African majorities in the territorial Legislative Councils. Following the I960 Raisman Commission and Report, the High Commission of governors was replaced in 1961 by the East African Common Services Authority composed of three elected leaders in each state. Under them were triumvirates of ministers from each country for communications, finance, commerce and industry, and social and research services. The Legislative Assembly was changed, to consist now of the members of the Authority, the triumvirates, and 27 representatives, nine from each country's Legislative Council. Again, the EACSA was not a federation. Significantly defence became a territorial instead of a regional responsibility.

The African members of the territorial legislatures, inspired by the pan-Africanist spirit emanating from Accra from 1958, were eager to establish a full political and economic federation in East Africa. Unlike the Africans in the Central African Federation, the East Africans were now free of the fear of settler domination. Also, in contrast to French-speaking West Africa, the decolonizing power in East Africa was not an obstacle to an African-led federation. Why, then, did East Africa fail to federate?

Julius Nyerere, attending the African Heads of State conference at Addis Ababa in June I960 as an observer, declared, 'We must confront the Colonial Office with a demand not , for the freedom of Tanganyika and then for Kenya and then Uganda and then Zambia, but with a demand for the freedom of East Africa as one political unit.' He offered to postpone Tanganyika's independence for several months so that the various territories could achieve independence and unity together.

“We will never, never sell our freedom for capital or technical aid. We

stand for freedom at any cost.” -Tom Mboya on 8th December 1959 as he

chaired the All Africa People’ s Conference

In Kenya the KANU caretaker leaders Gichuru and Mboya (Kenyatta still being in detention) supported Nyerere's proposal. But Ugandan leaders did not. The Kabaka, Sir Edward Mutesa, was doubtful about the federation of Buganda with the rest of Uganda, leave alone federation on a wider scale.

The Uganda People's Congress president, Milton Obote, was no more enthusiastic than the Kabaka. Obote commented, 'It is futile to try to think outside Uganda before solving internal problems. In the long run the idea is attractive.' The Ugandans' attitude provided London with an excuse to ignore Nyerere's proposal and delay Kenya's independence for a few more years, and Tanganyika, Uganda and Kenya became independent at different times.

Kabaka, Sir Frederrick Edward Mutesa Walugembe, was doubtful about the federation of Buganda with the rest of Uganda.

Nevertheless, the East African Common Services Authority was formed in 1961. Then on 5 June 1963, tour days after the achievement of Kenya's madaraka or internal self- government, and with Tanganyika and Uganda already independent.

"It is futile to try to think outside Uganda before solving internal problems."Milton Obote

President Nyerere, Prime Minister Obote arid Prime Minister Kenyatta issued the Declaration of Federation by the governments of East Africa. The Declaration announced that a working party had already been set up to prepare a draft federal constitution. The following year, however, was marked by events which effectively destroyed the spirit of East African unity and placed federation outside the realm of immediate practical possibility. In 1964 Tanganyika merged with revolutionary Zanzibar into Tanzania and moved towards a more radical form of socialism, thereby alarming both Kenya and Uganda.

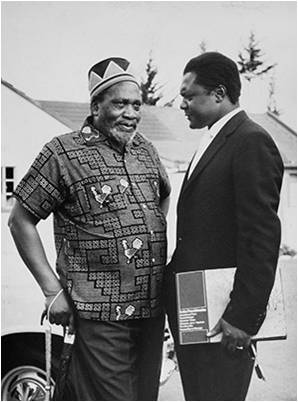

Kabaka Edward Mutesa with Obote at independence.

Nyerere and his government described Tanganyika union with Zanzibar as a step towards the goal of an East African federation. They were wrong. The narrower unification of Tanganyika and Zanzibar has harmed the ambition of a broader unification. Nothing could have dramatized more effectively the problems which would attend a prospective East African federation than the problems which almost at once arose in relations between Zanzibar and Tanganyika. Even in external affairs it seemed doubtful that the central government in Dar-es-Salaam could speak for the union as a whole. The prolonged argument as to which of the two Germanys was to have an embassy in Tanzania was one case in point.

Dr. Milton Obote making a statement

The moral of this whole experience is that there are occasions when a blind plunge into union is what is needed to make the union take place at all. The union of Tanganyika and Zanzibar did itself constitute such a sudden plunge. But once that took place, East Africa as a whole could no longer federate blindly - for the smaller union had opened the eyes of the region as a. whole to the difficulties involved in such a venture.

President Jomo Kenyatta with his Minister Tom Mboya

Another factor militating against the setting up of a federation was Tanzania's socialism. Ease Africa attained independence as an economic community, with a common market consisting in a flow of goods between the territories which was almost completely free, and common services which included a common currency.

Both these factors became a hindrance to Tanzania as she developed a planned economy within her own borders. At a conference on the co-ordination of economic planning in East Africa held in Entebbe on 17 March 1964, Tanzania's ministerial delegate Nsilo Nswai announced that Tanganyika was considering leaving the common market and setting up a separate currency. This helped to precipitate a crisis which culminated in the Kampala Agreement.

The Agreement allowed for quota restrictions on imports from each other, and allocated specialized industries to each partner. The common-market principle in East Africa was thus seriously diluted.

Summary reasons for the closer Union of East Africa

Britain wanted to unite all the three East African territories because of the following reasons.

The encouragement given by Lugard in 1898 is what inspired Britain to unite all the East African territories.

In 1900 sir Harry Johnston the British high commissioner to Uganda further encouraged Britain to unite East African states (Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyika).

The need to establish a common government with similar rules and regulations.

Britain wanted a greater East African Empire with one parliament and Judiciary.

The need to create a common market and common currency.

The need for free movement of goods and services in East Africa.

The railway line had already united Uganda and Kenya, so the federation seemed easer.

The need to avoid duplication of services in the three states.

Uganda and Kenya shared the same colonial masters (the British) i.e. they were already united.

The acquisition of Tanganyika after World war one, encouraged the British to make East Africa one state.

The British lacked manpower to administer the whole of East Africa.

Indirect rule was favourable and successful in all the three East African states.

The climatic conditions in East Africa were similar, so the administrators couldn't get climatic disturbances as they moved from place to place.

Cultural and linguistic similarities forced Britain to think that East Africans were one people e.g. both Kenya and Tanganyika spoke Kiswahili language, all states had-the Bantu and Luo tribes /speakers, shared the same lake Victoria and other aspects.

Britain wanted to cut down the cost of Administration by reducing the number of administrators.

The success of the British-Boer union in South Africa favoured the idea of closer union of East Africa.

National Movements and New States in Africa