The Roman system of government; the Roman empire

When Alexander the Great set out to seize a huge empire

and spread Greek culture in the fourth century B.C., the peoples who made up the

population of Italy were relatively insignificant in the world. They we

organized into a number of city states and agricultural communities. The most

important of these city states was Rome, said to have b founded in the eighth

century B.C., about the time when the Assyrian, were invading Israel. There

were two significant things to notice about Rome in the running of its affairs;

there was a strong emphasis on the duty of the citizen to be ready to serve his

state as a soldier at any time and there was considerable participation in the

affairs of the state by citizens who, from an early time, met in a civic

assembly. The ruler who did not have the support of the citizens did not hold

power for long. The way of life developed in Rome emphasized militarism, disciplined

organization and the duties and rights of citizens. A republican form of

government developed in which the rulers were elected by the citizens.

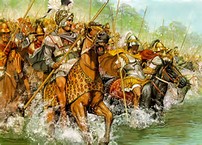

By the third century B.C. the Romans had extended control over Italy as a whole and through their military system, could call up about 800,000 men for military service from all over the country. Of these, about 70,000 could serve as cavalry (horse soldiers). To facilitate the easy movements of troops across the country, a system of roads was built. In later times, the Romans were to become the most famous road builders of all the ancient peoples.

roman horse soldiers

Before the end of the third century B.C. the strength of

Roman militarism had a severe testing during a long campaign of attempted

conquest of Italy by the Carthaginians from North Africa. The Carthaginian

general, Hannibal, who first invaded Italy in 218 B.C., was not finally

defeated until 202 B.C. What this hard period of war proved to the Romans was

that, with disciplined and experienced soldiers, they need not fear any other

people. During the long wars with the Carthaginians, they also mastered the

skills of sea warfare and became very efficient builders of large galleys which

were moved by rowers and sails.

From the beginning

of the second century B.C. onwards, the Romans took advantage of weak political

situations in the lands around the Mediterranean Sea to extend their control

over other peoples and to begin their empire building. The divided empire of

Alexander the Great had declined in power and would eventually fall to the

armies of Rome. By the end of the second century B.C. the Romans controlled

Spain, southern Gaul, Greece, Asia Minor and Carthage on the North African

coast. It was during the second century B.C. that Judas Maccabeus had asked for

help from the Romans in his fight against the Syrians.

It was during the first century B.C. and the first

century A.D. that the Romans succeeded in consolidating the largest empire that

the world had ever known. Their conquests extended round the Mediterranean

lands, east to Mesopotamia, north into Europe as far as the north-western

coast, west to Spain, and along the northern coast of Africa.

Rome had continued to be governed not as a kingdom but as

a republic, under elected consuls, but rivalries over leadership brought

problems. Shakespeare's famous play about the elected consul, Julius Caesar,

who was asked to be king and declined but actually had the powers of a

dictator, dramatizes some of the rivalries of the last half of the first

century B.C. Julius Caesar's adopted son, Octavian, who was later given the

title 'Augustus', meaning 'exalted one', was a very skilful ruler who

maintained the outward structure of a republic in which the Senate consisting

of leading citizens, elected the consul for a given period. However, although

elected consul, Augustus was a dictator in practice, particularly after he was

asked by the Romans to become the High Priest of Rome, because he then combined

in himself supreme political power and the highest religious authority. Augustus

was the first of' Roman rulers to be mentioned in the New Testament (Luke 2:1).

From Augustus onwards we refer to the Roman rulers as Emperors, meaning

Commanders, as they had supreme military as well as political power. The Roman

armies were the foundation of Roman power. When Augustus accepted the political

powers of the consul, the religious authority of the High Priest of Rome, and

the military command of the Roman armies, he became the most powerful ruler

that the ancient world had known.

We need not concern ourselves with the history of the

Roman empire after the first century A.D. but it is important to know that the

Christian faith began when Roman power and influence was at its height. This offered

opportunities for the spread of the new faith which did exist even a hundred

years earlier. 'But when the right time finally came, God sent his own Son'

(Galatians 4:4).

It was members of the family of Augustus who ruled the

Roman Empire during the first spread of the Christian faith, to the time when

Peter and Paul died. Augustus, who ruled from 31 B.C. to A.D. 14, was followed

by Tiberius (A.D. 14-37), who was followed by Caligula (A. 37-41). Caligula

became mad and was murdered by some of his army officers; his successor was his

uncle, Claudius, (A.D. 41-54). Claudi was succeeded by the notorious Nero (A.D.

54--68).