TOPIC 3: THE RISE AND FALL OF MALI

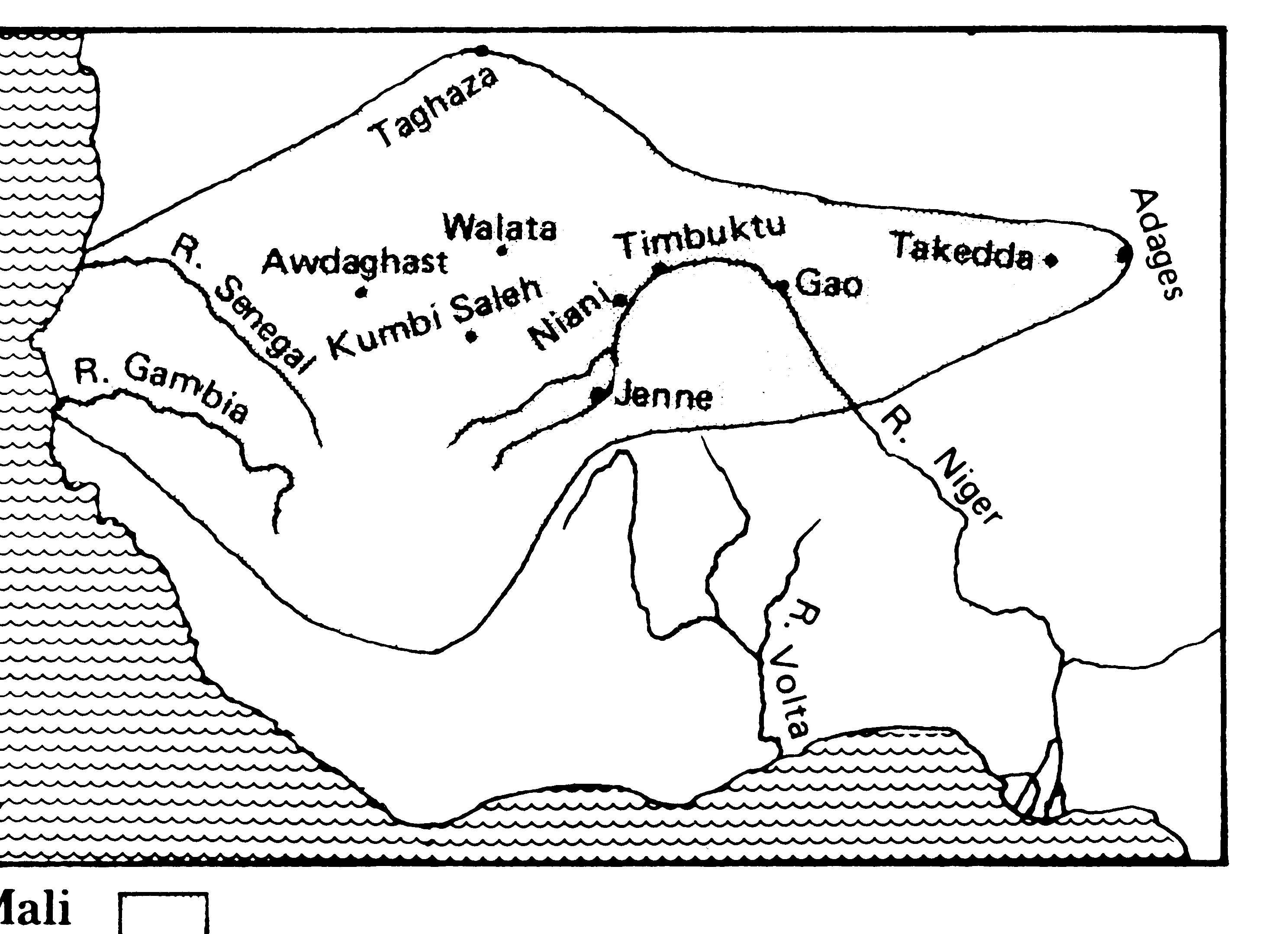

Mali which meant where the king resides grew out in the 11th century from the state of Kangaba. This was a former vassal or conquered state of Ghana. Mali was founded by Sundiata Keita who established his capital city initially at Jeriba and in 1240; Niani became the capital city of Mali.

Mali came into existence when Sundiata attacked the Susu or Soso kingdom of Sumanguru Kante. It was the Soso that contributed to the eventual collapse of Ghana.

Kangaba was situated right within the savanna belt from where Sundiata transformed it into a great empire after capturing Susu kingdom in 1240.The empire of Mali began to expand towards the south and south east at the beginning of the 13th century. Leaders like Sundiata Keita later led this empire to its glory.

The Mali Empire or Manding Empire or Manden Kurufa was a medieval Islamic West African state of the Mandinka from 1235 to 1645. The empire was founded by Sundiata Keita and became renowned for the wealth of its rulers, especially Mansa Musa I. The Mali Empire had many profound cultural influences on West Africa allowing the spread of its language, laws and customs along the Niger River.

Manden

The Mali Empire grew out of an area referred to by its contemporary inhabitants as Manden.[1] Manden, named for its inhabitants the Mandinka (initially Manden'ka with "ka" meaning people of),[2] comprised most of present-day northern Guinea and southern Mali. The empire was originally established as a federation of Mandinka tribes called the Manden Kurufa (literally Manden Federation), but it later became an empire ruling some 50 million people of nearly every ethnic group imaginable in West Africa.

Etymology

The naming origins of the Mali Empire are complex and still debated in scholarly circles around the world. While the meaning of "Mali" is still contested, the process of how it entered the regional lexicon is not. As mentioned earlier, the Mandinka of the Middle Ages referred to their ethnic homeland as "Manden".

Among the many different ethnic groups surrounding Manden were Pulaar speaking groups in Macina, Tekrur and Fouta Djallon. In Pulaar, the Mandinka of Manden became the Malinke of Mali. [3] So while the Mandinka people generally referred to their land and capital province as Manden, its semi-nomadic Fula subjects residing on the heartland's western (Tekrur), southern (Fouta Djallon) and eastern borders (Macina) popularized the name Mali for this kingdom and later empire of the Middle Ages.

Pre-Imperial Mali

The Mandinka kingdoms of Mali or Manden had already existed several centuries before Sundiata's unification as a small state just to the south of the Soninké empire of Wagadou, better known as the Ghana Empire.[4] This area was composed of mountains, savannah and forest providing ideal protection and resources for the population of hunters.[5] Those not living in the mountains formed small city-states such as Toron, Ka-Ba and Niani. The Keita dynasty from which nearly every Mali emperor came traces its lineage back to Bilal, [2] the faithful muezzin of Islam's prophet Muhammad. It was common practice during the Middle Ages for both Christian and Muslim rulers to tie their bloodline back to a pivotal figure in their faith's history. So while the lineage of the Keita dynasty may be dubious at best, oral chroniclers have preserved a list of each Keita ruler from Lawalo (supposedly one of Bilal's seven sons whom settled in Mali) to Maghan Kon Fatta (father of Sundiata Keita).

The Kangaba Province

During the height of Wagadou's power, the land of Manden became one of its provinces.[6] The Manden city-state of Ka-ba (present-day Kangaba) served as the capital and name of this province. From at least the beginning of the 11th century, Mandinka kings known as faamas ruled Manden from Ka-ba in the name of the Ghanas.[3]

The Twelve Kingdoms

Wagadou's control over Manden came to a halt after 14 years of war with the Almoravides, Muslim fanatics of mostly Berber extraction from North Africa. The Almoravide general Abu Bekr captured and burned the Wagadou capital of Kumbi Saleh in 1076 ending its dominance over the area. [4] However, the Almoravides were unable to hold onto the area, and it was quickly retaken by the weakened Soninké. The Kangaba province, free of both Soninké and Berber influence, splintered into twelve kingdoms with their own maghan (meaning prince) or faama.[5] Manden was split in half with the Dodougou territory to the northeast and the Kri territory to the southwest.[7] The tiny kingdom of Niani was one of several in the Kri area of Manden.

The Kaniaga Rulers

In approximately 1140 the Sosso kingdom of Kaniaga, a former vassal of Wagadou, began conquering the lands of its old masters. By 1180 it had even subjugated Wagadou forcing the once proud Soninké to pay tribute. In 1203, the Sosso king Soumaoro of the Kanté clan came to power and reportedly terrorized much of Manden stealing women and goods from both Dodougou and Kri.[8]

The Lion Prince

During the rise of Kaniaga, Sundiata of the Keita clan was born around 1217 AD. He was the son of Niani's faama, Nare Fa (also known as Maghan Kon Fatta meaning the handsome prince). Sundiata's mother was Maghan Kon Fatta's second wife, Sogolon Kédjou.[2] She was a hunchback from the land of Do south of Mali. The child of this marriage received the first name of his mother (Sogolon) and the surname of his father (Djata). Combined in the rapidly spoken language of the Mandinka, the names formed Sondjata or Sundjata.[2] The anglicized version of this name, Sundiata, is also popular. Maghan Sundiata was prophesized to become a great conqueror. To his parent's dread, the prince did not have a promising start. Maghan Sundiata, according to the oral traditions, did not walk until he was seven years old.[5]

However, once Sundiata did gain use of his legs he grew strong and very respected. Sadly for Sundiata, this did not occur before his father died. Despite the faama of Niani's wishes to respect the prophecy and put Sundiata on the throne, the son from his first wife Sassouma Bérété was crowned instead. As soon as Sassouma's son Dankaran Touman took the throne, he and his mother forced the increasingly popular Sundiata into exile along with his mother and two sisters. Before Dankaran Touman and his mother could enjoy their unimpeded power, King Soumaoro set his sights on Niani forcing Dankaran to flee to Kissidougou.[2]

After many years in exile, first at the court of Wagadou and then at Mema, Sundiata was sought out by a Niani delegation and begged to combat the Sosso and free the kingdoms of Manden forever.

Battle of Kirina

Returning with the combined armies of Mema, Wagadou and all the rebellious Mandinka city-states, Maghan Sundiata led a revolt against the Kaniaga Kingdom around 1234. The combined forces of northern and southern Manden defeated the Sosso army at the Battle of Kirina (then known as Krina) in approximately 1235.[5] This victory resulted in the fall of the Kaniaga kingdom and the rise of the Mali Empire. After the victory, King Soumaoro disappeared, and the Mandinka stormed the last of the Sosso cities. Maghan Sundiata was declared "faama of faamas" and received the title "mansa", which translates roughly to emperor. At the age of 18, he gained authority over all the twelve kingdoms in an alliance known as the Manden Kurufa.[9] He was crowned under the throne name Mari Djata becoming the first Mandinka emperor.[5]

Manden Kurufa

The Mali Empire was the second in a wave of successive states forged in the Sahel characterized by stronger and stronger centralization. Whereas the Ghana Empire had very little centralization outside of the edicts of its emperor, the Mali Empire would emerge as West Africa's first federalized state with sweeping laws that were more or less uniform over an area roughly the size of Western Europe. This trend of centralization would be adopted and further developed by the Songhai during Mali's decline as well as Bamana, Wolof and Fula states thereafter.

Organization

The Manden Kurufa founded by Mari Djata I was composed of the "three freely allied states" of Mali, Mema and Wagadou plus the Twelve Doors of Mali.[2] It is important to remember that Mali, in this sense, strictly refers to the city-state of Niani.

Mema was a powerful city-state near the bend of the Niger River outside of Manden. It was allied to Sundiata throughout his campaign against Kaniaga. Its faama (sometimes referred to as a mansa in oral traditions) was allowed to keep his crown and not prostrate before Sundiata, because of the latter's exile at that court.

Wagadou, another land outside of Manden, was also allowed to keep its monarch. The Ghana ("warrior-king") of Wagadou received the same benefits as Mema and for the same reasons.

The twelve doors of Mali were a coalition of conquered or allied territories, mostly within Manden, with sworn allegiance to Sundiata and his descendants. Upon stabbing their spears into the ground before Sundiata's throne, each of the twelve kings relinquished their kingdom to the Keita dynasty.[2] In return for their submission, they became "farbas" a combination of the Mandinka words "farin" and "ba" (great farin).[6] Farin was a general term for northern commander at the time. These farbas would rule their old kingdoms in the name of the mansa with most of the authority they held prior to joining the Manden Kurufa.

The Kouroukan Fouga

Immediately after being crowned mansa, Mari Djata instituted a universal constitution for all subjects of his new state called the Kouroukan Fouga.[10] At a site just outside the town of Kangaba, he formalized the government and established the Gbara or Great Assembly.[11]

The Great Assembly

The Gbara or Great Assembly would serve as the Mandinka deliberative body until the collapse of the Manden Kurufa in 1645. Its first meeting, at the famous Kouroukan Fouga (Division of the World), had 29 clan delegates presided over by a belen-tigui (master of ceremony). The final incarnation of the Gbara, according to the surviving traditions of northern Guinea, held 32 positions occupied by 28 clans.[12]

Social, Economic and Government Reform

The Kouroukan Fouga also put in place social and economic reforms including prohibitions on the maltreatment of prisoners and slaves, installing women in government circles and placing a system of banter between clans which clearly stated who could say what about in who. Also, Sundiata divided the lands amongst the people assuring everyone had a place in the empire and fixed exchange rates for common products.

Another crucial fact established at the Kouroukan Fouga was the supremacy of Manden over all realms controlled by or allied to the federation including Wagadou and Mema. All future mansas would have to be chosen from the Keita clan, and the city-state of Niani (in present-day Guinea) would become the federal capital. Mansa Mari Djata returned to and rebuilt the capital of Niani, which had been destroyed by Soumaoro in his absence, and made it the most important center of trade in West Africa for the next 200 years.

Mari Djata I

Mansa Mari Djata's reign saw the conquest and or annexation of several key locals in the Mali Empire. When the campaigning was done, his empire extended 1,000 miles east to west with those borders being the bends of the Senegal and Niger Rivers respectively.[13] After unifying Manden, he added the Wangara goldfields making them the southern border. The northern commercial towns of Oualata and Audaghost were also conquered and became part of the new state's northern border. Wagadou and Mema became junior partners in the realm and part of the imperial nucleus. The lands of Bambougou, Jalo (Fouta Djallon) and Kaabu were added into Mali by Fakoli Koroma,[5] Fran Kamara and Tiramakhan Traore,[14] respectively.

When Mari Djata I dies, as the result of either drowning in the Sankarani or an errant arrow in a celebration, he had a standing army and control over the coveted trans-Saharan trade routes.[2]

Imperial Mali

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Great_Mosque_of_Djenn%C3%A9_1.jpgRebuilt Mosque of Djenne

There were 21 known mansas of the Mali Empire after Mari Djata I and probably about two or three more yet to be revealed. The names of these rulers come down through history via the djelis and modern descendants of the Keita dynasty residing in Kangaba. What separates these rulers from the founder, other than the latter's historic role in establishing the state, is their transformation of the Manden Kurufa into a Manden Empire. Not content to rule fellow Manding subjects unified by the victory of Mari Djata I, these mansas would conquer and annex Peuhl, Wolof, Serer, Bamana, Songhai, Taureg and countless other peoples into an immense empire.

The Djata Lineage 1250-1275

The first three successors to Mari Djata all claimed it by blood right or something close to it. This twenty-five year period saw amazing gains for the mansa and the beginning of fierce internal rivalries that nearly ended the burgeoning empire.

Ouali I

After Mari Djata's death in 1255, custom dictated that his son ascend the throne assuming he was of age. However, Yérélinkon was a minor following his father's death.[15] Manding Bory, Mari Djata's half-brother and kankoro-sigui (vizier), should have been crowned according to the Kouroukan Fouga. Instead, Mari Djata's son seized the throne and was crowned Mansa Ouali (also spelt "Wali").

Mansa Ouali proved to be a good emperor adding more lands to the empire including the Gambian provinces of Bati and Casa. He also conquered the gold producing provinces of Bambuk and Bondou. The central province of Konkodougou was established. The Songhai kingdom of Gao also seems to have been subjugated for the first of many times around this period.

Aside from military conquest, Ouali is also credited with agricultural reforms throughout the empire putting many soldiers to work as farmers in the newly acquired Gambian provinces. Just prior to his death in 1270, Ouali went on the hajj to Mecca strengthening ties with North Africa and Muslim merchants.

The General's Sons

As a policy of controlling and rewarding his generals, Mari Djata adopted their sons. [5] These children were raised at the mansa's court and became Keitas upon reaching maturity. Seeing the throne as their right, two adopted sons of Mari Djata waged a devastating war against one another that threatened to destroy what the first two mansas had built. The first son to gain the throne was Mansa Ouati (also spelt "Wati) in 1270.[7] He reigned for four years spending lavishly and ruling cruelly according to the djelis. Upon his death in 1274, the other adopted son seized the throne.[7] Mansa Khalifa is remembered as even worse than Ouati. He governed just as badly and reportedly fired arrows from the roof of his palace at passersby. He was assassinated, possibly on orders of the Gbara, and replaced with Manding Bory in 1275.

The Court Mansas 1275-1300

After the chaos of Ouali and Khalifa's reigns, a number of court officials with close ties to Mari Djata ruled. They began the empire's return to grace setting it up for a golden age of rulers.

Abubakari I

Manding Bory was crowned under the throne name Mansa Abubakari (a Manding corruption of the Muslim name Abu Bakr).[5] Mansa Abubakari's mother was Namandjé,[5] the third wife of Maghan Kon Fatta. Prior to becoming mansa, Abubakari had been one of his brother's generals and later his kankoro-sigui. Little else is known about the reign of Abubakari I, but it seems he was successful in stopping the hemorrhaging of wealth in the empire.

Sakoura

In 1285, a court slave freed by Mari Djata whom had also served as a general usurped the throne of Mali.[4] The reign of Mansa Sakoura (also spelt Sakura) appears to have been beneficial despite the political shake-up. He added the first conquests to Mali since the reign of Ouali including the former Wagadou provinces of Tekrour and Diara. His conquests did not stop at the boundaries of Wagadou however. He campaigned into Senegal and conquered the Wolof province of Dyolof then took the army east to subjugate the copper producing area of Takedda. He also conquered Macina and raided into Gao[4] More than just a mere warrior, Mansa Sakoura went on the hajj and opened direct trade negotiations with Tripoli and Morocco.[4] to suppress its first rebellion against Mali.

Mansa Sakoura was murdered on his return trip from Mecca in or near present-day Djibouti by a Danakil warrior attempting to rob him.[17] The emperor's attendants rushed his body home through the Ouaddai region and into Kanem where one of that empire's messengers was sent to Mali with news of Sakoura's death. When the body arrived in Niani, it was given a regal burial despite the usurper's slave roots.[18]

The Kolonkan Lineage 1300-1312

The Gbara selected Ko Mamadi as the next mansa in 1300. He was the first of a new line of rulers directly descending from Mari Djata's sister, Kolonkan.[5] But seeing as how these rulers all shared the blood of Maghan Kon Fatta, they are considered legitimate Keitas. Even Sakoura, with his history of being a slave in the Djata family, was considered a Keita; so the line of Bilal had yet to be broken.

It is during the Kolonkan lineage that the defining characteristics of golden age Mali begin to appear. By maintaining the developments of Sakoura and Abubakari I, the Kolonkan mansas steer Mali safely into its apex.

Economy

The Mali Empire flourished because of trade above all else. It contained three immense gold mines within its borders unlike the Ghana Empire, which was only a transit point for gold. The empire taxed every ounce of gold or salt that entered its borders. By the beginning of the 14th century, Mali was the source of almost half the Old World's gold exported from mines in Bambuk, Boure and Galam.[4] There was no standard currency throughout the realm, but several forms were prominent by region.

Gold

Mansa Musa depicted holding a gold nugget from a 1395 map of Africa and Europe

Gold nuggets were the exclusive property of the mansa, and were illegal to trade within his borders. All gold was immediately handed over to the imperial treasury in return for an equal value of gold dust. Gold dust had been weighed and bagged for use at least since the reign of the Ghana Empire. Mali borrowed the practice to stem inflation of the substance, since it was so prominent in the region. The most common measure for gold within the realm was the ambiguous mithqal (4.5 grams of gold).[5] This term was used interchangeably with dinar, though it is unclear if coined currency was used in the empire. Gold dust was used all over the empire, but was not valued equally in all regions.

Salt

Tuaregs were and still are an integral part of the salt trade across the Sahara

The next great unit of exchange in the Mali Empire was salt. Salt was as valuable if not more valuable than gold in Sub-Saharan Africa. It was cut into pieces and spent on goods with close to equal buying power throughout the empire.[5] While it was as good as gold in the north, it was even better in the south. The people of the south needed salt for their diet, but it was extremely rare.[19] The northern region on the other hand had no shortage of salt. Every year merchants entered Mali via Oualata with camel loads of salt to sell in Niani. According to historians of the period, a camel load of salt could fetch 10 dinars worth of gold in the north and 20 to 40 in the south.[5]

Copper

Copper was also a valued commodity in imperial Mali. Copper, traded in bars, was mined from Takedda in the north and traded in the south for gold. Contemporary sources claim 60 copper bars traded for 100 dinars of gold.[5]

Military

The number and frequency of conquest in the late 13th century and throughout the 14th century indicate the Kolonkan mansas inherited and or developed a capable military. While no particular mansa or mansa has ever been credited with the organization of the Manding war machine, it could not have developed to the legendary proportions proclaimed by its subjects without steady revenue and stable government. Conveniently, the Mali Empire had just that from 1275 until the first Kolonkan mansa in 1300.

Strength

The Mali Empire maintained a professional, full-time army in order to defend its borders. The entire nation was mobilized with each tribe obligated to provide a quota of fighting age men.[5] Contemporary historians present during the height and decline of the Mali Empire consistently record its army at 100,000 with 10,000 of that number being made up of cavalry.[5] With the help of the river tribes, this army could be deployed throughout the realm on short notice.[20]

Divisions

The forces were divided into northern and southern armies. The northern army, under the command of a farin (northern commander) was stationed in the border city of Soura.[5] The southern army, under the command of a Sankar (a term for the ruler near the Sankarani River),[5] was commanded from the city of Zouma. The Farin-Soura and Sankar-Zouma were both appointed by the mansa and answerable only to him.

Infantry

Djenne Terracotta depicting an archer from Mali Empire dated around 13-15th Century.

An infantryman, regardless of weapon (bow, spear, etc.) was called a sofa.[2] Sofas were organized into tribal units under the authority of an officer called the kelé-kun-tigui or "war-tribe-master".

The kelé-kun-tigui could be the same or a separate post from that of the kun-tigui (tribe-master). Kun-Tiguis held complete authoirty over the entire tribe and were responsible for filling the quota of men his tribe had to submit for Mali's defense. Along with this responsibility was the duty of appointing or acting as kelé-kun-tigui for the tribe. Despite their power over infantry forces of their own tribe, kelé-kun-tiguis were more likely to fight on horseback.

Below the kelé-kun-tigui were two officers. The most junior of these was the kelé-kulu-kun-tigui who commanded the smallest unit of infantry called a kelé-kulu meaning "war heap" consisting of 10 to twenty men. A unit of ten kelé-kulus (100 to 200 infantry" was called a kelé-bolo meaning "war arm". The officer in charge of this unit was called a kelé-bolo-kun-tigui.[21]

Cavalry

Djenne Terracotta Equestrian figure found in Mali Empire region and dated approximately 13-15th Century

Cavalry units called Mandekalu served as an equal if not more important element of the army. Then as today, horses were expensive and only the nobles took them into battle. A Mandinka cavalry unit was composed of 50 horsemen called a seré commanded by a kelé-kun-tigui. Kélé-Kun-Tiguis, as the name suggest, were professional soldiers and the highest rank on the field short of the Farin or Sankar.

Equipment

The common sofa was armed with a large shield constructed out of wood or animal hide and a stabbing spear called a tamba. Bowmen formed a large portion of the sofas. Three bowmen supporting one spearman was the ratio in Kaabu and the Gambia by the mid 16th century. Equipped with two quivers and a shield, Mandinka bowmen used iron headed arrows with barbed tipped that were usually poisoned. They also used flaming arrows for siege warfare. While spears and bows were the mainstay of the sofas, swords and lances of local or foreign manufacture were the choice weapons of the Mandekalu.[22] Another common weapon of Mandekalu warriors was the poison javelin used in skirmished. Imperial Mali's horsemen also used chain mail armor for defense and shields similar to those of the sofas

The Gao Mansas

Ko Mamadi was crowned Mansa Gao and ruled over a successful empire without any recorded crisis. His son, Mansa Mohammed ibn Gao, ascended the throne five years later and continued the stability of the Kolonkan line.[5]

Abubakari II

The last Kolonkan ruler, Bata Manding Bory, was crowned Mansa Abubakari II in 1310.[5] He continued the non-militant style of rule that characterized Gao and Mohammed ibn Gao, but was interested in the empire's western sea. According to an account given by Mansa Musa I, who during the reign of Abubakari II served as the mansa's kankoro-sigui, Mali sent two expeditions into the Atlantic. Mansa Abubakari II left Musa as regent of the empire, demonstrating the amazing stability of this period in Mali, and departed with the second expedition commanding some 4,000 pirogues equipped with both oars and sails in 1311.[22] Neither the emperor nor any of the ships returned to Mali. Modern historians and scientists are skeptical about the success of either voyage, but the account of these happenings is preserved in both written North African records and the oral records of Mali's djelis

The Laye Lineage 1312-1389

Abubakari II's 1312 abdication, the only recorded one in the empire's history, marked the beginning of a new lineage descended from Faga Laye.[5] Faga Laye was the son of Abubakari I. Unlike his father, Faga Laye never took the throne of Mali. However, his line would produce seven mansa whom reigned during the height of Mali's power and toward the beginning of its decline.

Administration

The Mali Empire covered a larger area for a longer period of time than any other West African state before or since. What made this possible was the decentralized nature of administration throughout the state. According to Ki-Zerbo, the farther a person traveled from Niani, the more decentralized the mansa's power became.[23] Nevertheless, the mansa managed to keep tax money and nominal control over the area without agitating his subjects into revolt. At the local level (village, town, city), kun-tiguis elected a dougou-tigui (village-master) from a bloodline descended from that locality's semi-mythical founder.[8] The county level administrators called kafo-tigui (county-master) were appointed by the governor of the province from within his own circle.[4] Only when we get to the state or province level is there any palpable interference from the central authority in Niani. Provinces picked their own governors via their own custom (election, inheritance, etc). Regardless of their title in the province, they were recognized as dyamani-tigui (province master) by the mansa.[4] Dyamani-tiguis had to be approved by the mansa and were subject to his oversight. If the mansa didn't believe the dyamani-tigui was capable or trustworthy, a farba might be installed to oversee the province or administer it outright.

Farins and Farbas

Territories in Mali came into the empire via conquest or annexation. In the event of conquest, farins took control of the area until a suitable native ruler could be found. After the loyalty or at least the capitulation of an area was assured, it was allowed to select its own dyamani-tigui. This process was essential to keep non-Manding subjects loyal to the Manding elites that ruled them.

Barring any other difficulties, the dyamani-tigui would run the province by himself collecting taxes and procuring armies from the tribes under his command. However, territories that were crucial to trade or subject to revolt would receive a farba.[24] Farbas were picked by the mansa from the conquering farin, family members or even slaves. The only real requirement was that the mansa knew he could trust this individual to safeguard imperial interests.

Duties of the farba included reporting on the activities of the territory, collecting taxes and ensuring the native administration didn't contradict orders from Niani. The farba could also take power away from the native administration if required and raise an army in the area for defense or putting down rebellions.[25]

The post of a farba was very prestigious, and his descendants could inherit it with the mansa's approval. The mansa could also replace a farba if he got out of control as in the case of Diafunu.

Territory

The Mali Empire reached its largest size under the Laye mansas. During this period, Mali covered nearly all the area between the Sahara Desert and coastal forests. It stretched from the shores of the Atlantic Ocean to Niamey in modern day Niger. By 1350, the empire covered approximately 439,400 square miles. The empire also reached its highest population during the Laye period ruling between 40 and 50 million people in 400 cities,[26] towns and villages of various religions and ethnicities. Scholars of the era claim it took no less than a year to traverse the empire from east to west. During this period only the Mongol Empire was larger.

The dramatic increase in the empire's size demanded a shift from the Manden Kurufa's organization of three states with twelve dependencies. This model was scrapped by Ibn Battuta's 1352 visit. Replacing the old model was a setup of fourteen provinces covering all areas loyal to the mansa.[27] The fourteen provinces included:

- Audaghost (Northeast of Takrur, West of Oulata)

- BaGhana ("Great Ghana" contains Wagadou and Mema)

- Bambougou (contains Bambuk and Boure conquered by Fakoli Koroma)

- Bati (The area immediately north of the Gambia)

- Cassa (Senegal South of the Gambia)

- Diafunu (contains Diara; NE of Bambouk, SE of Audaghost, SW of Oulata)

- Dyolof (Atop Senegal River)

- Gao (East of Niger northernmost hump)

- Kaabu (south of Cassa, west of Manden, most of northern Guinea Bissau)

- Kita (In SE region of the Kayes division of modern Mali, West of Bambouk)

- Konkodougou (West of Sangala, Possibly southwest of Kita)

- Manden (Capital province from which the empire gets it name; South of Kita)

- Oualata (East of Audaghost, West of Timbuktu; directly north of Kumbi Saleh)

- Takrur (On 3rd cataract of the Senegal River, north of Dyolof)

Reasons for the Rise of Mali.

Better geographical location contributed to the growth of Mali. The empire was advantaged that it was situated that within savanna belt and the fertile plain lands. For this reason, it produced enough food for the population, the army and the surplus was sold.

Secondly, the existence of Gold contributed to the growth of Mali empire. Mali controlled the gold producing regions of Bambuk and Wangara which made the- main supplier of gold in the Trans- Saharan trade, this attracted many trading caravans from the North to Mali kingdom. Through this, Mali acquired a lot of wealth.

The Trans-Saharan trade had a great contribution to the expansion of Mali empire. The empire of Mali controlled the Trans-Saharan trade especially after their diversion of trade from Ghana as a result of the Almoravids attack. This gave Mali an upper hand in the Trans-Saharan trade and also acquiring more wealth.

Lack of any strong resistance made it easy for Mali empire to expand with ease. The fall of Ghana created a power vacuum on which Mali was founded. Intact the empire did not face any threat or resistance from other vassal states.

The introduction of Islam played a very role to the growth of Mali empire. Mali became powerful because of its acceptance of Islam which united the people of Mali. islam created peace, order, and harmony which were essential for the development of Mali.

The able and strong leaders the empire had led to its development. The empire was blessed with leaders like -the founder Sundiata Keita who was able and dedicated and Mansa Musa Kankan, Mali experienced a period of growth and prosperity.

The oppressive rule of Sumanguru also led to the fall of Mali. This forced the Mandingo people of Kangaba to unite and rise against Sumanguru's oppression rule. In fact Kangaba took advantage of its leaders like Sundiata who turned the small state of Kangaba into a powerful and a strong empire.

Mali's strong army also contributed to the development of Mali. The empire had a strong army which was composed of former professional hunters and it was commanded by able generals. It was instrumental in expansion and maintenance of Mali empire.

The wealth acquired also helped. Mali was a rich state which got most of its wealth from agriculture and fishing but above all, it got a lot of revenue from the Trans-Saharan trade, especially on the taxes imposed. This strengthened Mali's economic and political areas.

The Achievements and Career of Sundiata Keita (1234-1255)

A leader was really founder in the person of person of Sundiata Keita. He was born a cripple and later recovered. He was originally called Mari-Jata, which means the Lord of Lions.

Fearing the conflicts in the royal family and the direct invasion of Sumanguru, Sundiata left his home at the court in Niani and went into exile. He therefore exploited the political situation to come to power.

Keita ruled Mali from probably 1230 to 1255. In fact, he is regarded by many historians as the founder of Mali empire.

His reign saw the transformation of the small kingdom of Kangaba into a great empire of Mali. With the assistance of his able generals, he was able to expand the boundaries of the small principality of Kangaba and extended it further for example he conquered and captured the gold producing areas of Walata and Bambuk and the salt mines of Taghaza.

Sundiata also expanded the empire to include the important trading routes and towns of Walata, Jenne, Timbuktu and Gao. These were very important commercial towns in Western Sudan.

Another remarkable contribution of Sundiata was the transfer of the capital from Jeriba to Niani in 1240. This was further up the Niger river which was a strategic location for effective management of the empire and control of the trade.

Sundiata also created a strong efficient army. The army was commanded by able and reputable generals. It was responsible for expanding the empire and defending it, keeping law and order and ensuring the proper collection of taxes.

Sundiata also encouraged and improved on the Trans-Sahara trade; for instance, he promoted the gold trade and the gold mines were well maintained. In fact because of the Trans-Saharan trade, there was a good relationship between the king and the traders.

He also promoted agriculture; He encouraged people to cultivate and weave clothes. He emphasized the growing of food crops to ensure food security,

Sundiata Keita was able to achieve the seemingly impossible task mainly because of the favourable positron of his empire, the prevailing political conditions, his courage, wisdom and ability.

Keita died in 1255 after effectively putting down the foundation of his empire and providing it with a new capital city, Niani.

MANSA KANKAN MUSA (1312-1337)

He was perhaps the greatest, famous and most remembered king of Mali. He was the grand son of Sundiata Keita. He ruled Mali from 1307 to 1337. His fame was due to the achievements in the areas of politics, commerce, education and religion.

Politically he extended the boundaries of Mali. In fact he consolidated Sundiata's policy of expansion by conquering Walata. He further captured Timbuktu and Gao.

Mansa Musa administered justice and impartiality. He saw to it that justice was done. He always invited and dealt with complaints and appeals against the oppression by the governors. It is this form of justice that won him fame and created peace and harmony.

Like Sundiata, Mansa Musa established a strong standing army; his army comprised of 100,000 men, 10,000 of these were horsemen. With this army, tightened his grip on the central government and in the provinces. He ensured peace, law and order and also the effective collection of taxes.

Further, Mansa Musa established a more efficient administrative system. He divided the empire into provinces and appointed a governor known as Emir who was mainly responsible for maintaining law and collection of taxes.

He also devoted himself to the civil service. In fact he created national honours one of them known as The Honour of Trouser. This was the highest, and was given to distinguished individuals for their services. This improved on the working force in the central government and the provinces.

Economically, he encouraged and improved trade. In fact the empire of Mali enjoyed economic prosperity under Mansa Musa and it was second to none in Western Sudan. He firmly controlled the gold mine areas of Wangala and Bambuk and also the salt producing areas or Taghaza. In these areas, he created peace and stability which increased Mali's revenue.

Mansa Musa's pilgrimage to Mecca

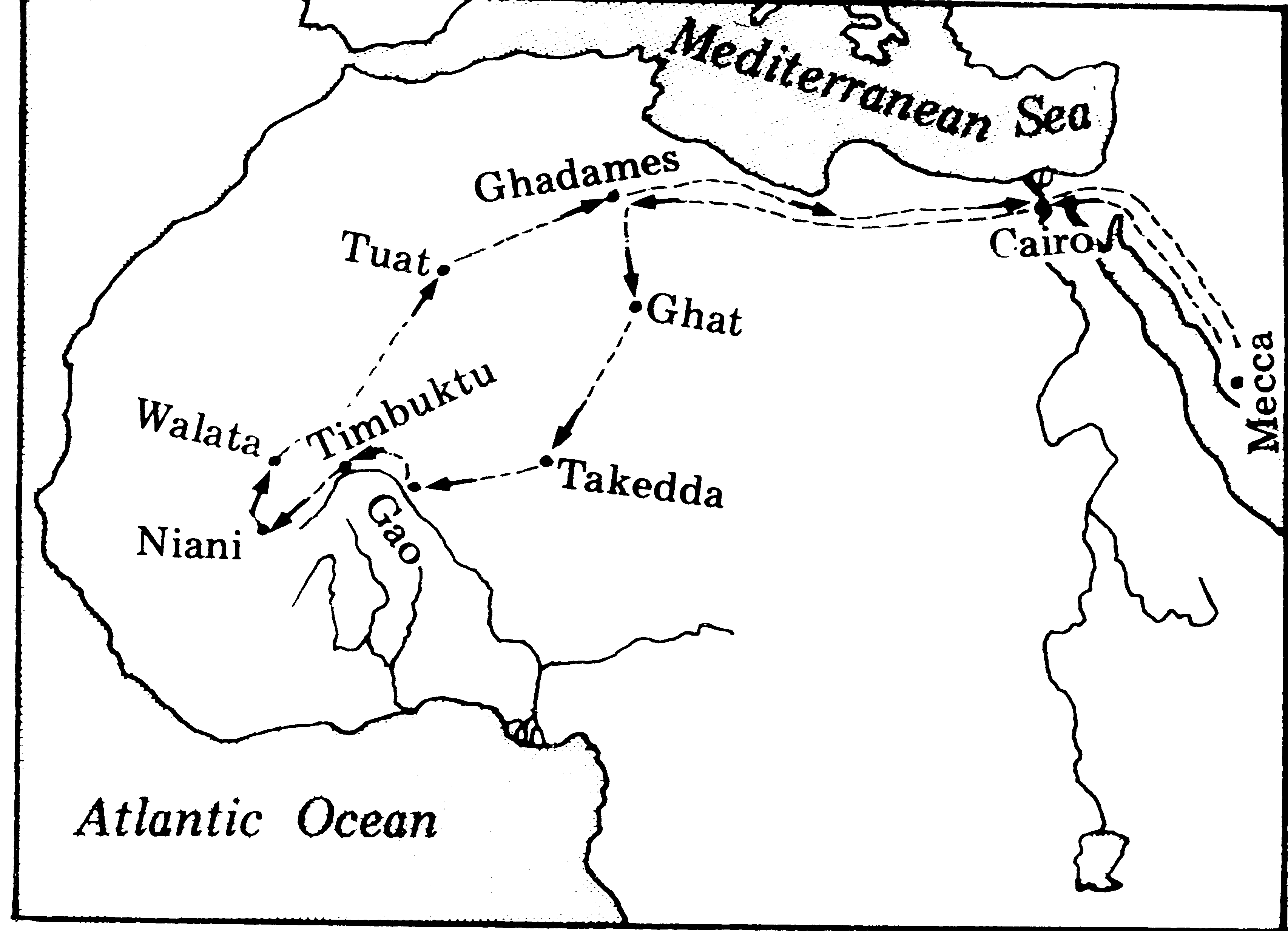

On the diplomatic front, he improved his foreign relationship. On the issue of foreign affairs, he was friendly with Morocco and Egypt. It is on record that he exchanged diplomats and gold with the king of Morocco, sultan Abu-al-Hasan.

Like Sundiata, he also ensured proper management of the Trans -Saharan trade in his empire. With the assistance of his army for example, he kept law and order and maintained security along the trade routes. As a result this attracted traders from many parts of the world as far as Egypt, and Libya and the commercial cities of Timbuktu, Gao and Jenne.

He also contributed to the development and growth of cities, like Jenne, Gao, Timbuktu and Niani.

Mansa Musa also encouraged the spread of islam and also made it a state religion. He used it to maintain social order in Mali which created peace, harmony and united the people.

He also made a pilgrimage to Mecca from 1324 to 1325. This pilgrimage made history in the Moslem world. He took with him 60,000 beautifully dressed attendants and 100 camels loaded with gold. The wealth and splendor which he displayed was the talk of the middle -east and in the centuries after.

This pilgrimage brought great fame to Mali, Europe and Arabia and earned Mali a place on the world map. The gold he carried was given to the poor in Egypt and Arabia.

On his return he brought with him a number of distinguished Muslim scholars, architects, technical experts who assisted in the construction of mosques and spreading of Islam.

In education, he encouraged and promoted islamic education. With the help of the scholars, Timbuktu became a centre of learning and he established Sankole University.

He also purified and strengthened islam by building mosques. He strictly as an example observed Islamic laws which he also encouraged the Mali people to do.

By the time of his death, in 1337, Mali extended from Atlantic in the West to Dendi in the East and from Walata, Arawan in the Sahara to Futa Jalon in the East. It is no wonder that Mansa Munsa Kankan was the greatest and most remembered king in Mali.

According to Ali Mazrui, the Mali Empire produced one pilgrimage which was itself a symbol of "God, gold and glory." Mali Emperor Mansa Moussa decided to go on a pilgrimage to Mecca in a huge caravan of "God, gold and glory." The trip to Mecca was overland through Cairo. Mansa Moussa is reported to have arrived in Cairo with an entourage of 60,000 people, 80 camels carrying over two tons of gold for distribution to the poor and the pious. Mansa Moussa was so lavish in his generosity in Egypt that the value of gold almost collapsed on the Egyptian gold market.

When in our own times the second millennium was coming to an end in the year 1999, Life magazine included Mansa Moussa's pilgrimage to Mecca in the fourteenth century among the great events of the whole millennium - a remarkable celebration indeed of "God, gold and glory."

Mansa Moussa's pilgrimage was a matter of recorded history. But there is an element about the Mali Empire which is a matter more of historical speculation than of historical confirmation. Did Abubakari II of Mali [Emperor Bakari II] launch a fleet to cross the Atlantic generations before Christopher Columbus traversed the ocean blue in 1492? Did the Empire which produced the glories of Timbuktu also produce the glories of a Black trans-Atlantic crossing long before Christopher Columbus? This latter claim is more hotly debated than Mansa Moussa's trans-Saharan odyssey. But both have entered the grand legends of the Black Experience.

There is a third huge topic which touches upon the historical interaction between the people of the southern margins of the Sahara like Mali and Niger and those of northern Sahara like Moroccans, Tunisians and Egyptians. Are we to trace the origins of the name "Africa" to the historic interaction between so-called Berber people of northern Sahara and the trans-Saharan Tuaregs all the way to Mali?[1]

The Decline of Mali

The decline of Mali empire started in the 2nd half of the 14th century. In fact by the beginning of the -15th century, it had shrunk into a tiny principality of Kangaba. The factors responsible for its decline were both within and out. The factors include;

The size and extent of Mali. Mali was too big to be effectively administered from one centre. It is worth noting that the means of communication during those days was poor and the empire also needed leaders with courage and the ability to administer such a big empire.

Lack of competent and skilled administrators: Mali after the death of leaders like Mansa Munsa never witnessed better leadership for example Mansa Musa's son king Magha carelessly allowed complete freedom to the princes Ali Kolen and Sulayman who proclaimed themselves independent.

The extravagant and corrupt leaders led to the fall of Mali. King Mansa Musa II (1373-1387) was cruel, very extravagant, wicked and above all corrupt. It is said that during his reign, he emptied the state treasury and also sold the gold which had been kept by other kings.

Internal disputes also led to the collapse of Mali. Because of political incompetence and rivalry among leaders, Mali never witnessed any political stability. In fact after the death of Sulayiman a civil war broke out between the rival contestants to the throne. It is on record that between 1360 and 1400 AD, Mali had more than 6 kings, this weakened the kingdom.

The weakness of the army contributed to the collapse of Mali. Because of poor leadership and incompetence, Mali army was terribly weakened. For this reason, it was unable to stop the vassal or conquered states from regaining their independence. In 1375 Gao revolted and became independent and the army was unable to stop this rebellion.

External pressure or threat contributed to the collapse of Mali. Mali was attacked by the Tuaregs from the North who captured Timbuktu, Walata and some parts of the northern region. The Mossi also raided the thousand frontiers of Mali. These external attacks weakened Mali.

Lack of unity also led to the fall of Mali. Mali had diverse cultures that contributed to its downfall. The leaders of Mali failed to unite the vassal states with different ethnic groups. This greatly influenced the decline of Mali.

Lastly the rise of Songhai also led to the fall of Mali. The rise of Songhai under Sunni Ali accelerated the decline of Mali. By l368, Sunni Ali had started raiding Mali and by the beginning of the 15th century Mali was completely annexed by Songhai. This marked the end of Mali empire and the rise of Songhai.

[1] Keynote address by Prof. Ali A. Mazrui at symposium on the theme, "Bridging to Connect: African Roots in Islam and History," sponsored by the Timbuktu Education Foundation, and held in Hayward (near San Francisco), California, Saturday, November 6, 2004.