The fifth Pan-African Congress or the 1945 Manchester conference

The first four pan-African congresses between 1900 and 1945 achieved nothing towards political self-determination in Africa. The 1945 Congress, however, at least achieved the development of an awareness among English-speaking pan-Africanist nationalists that the colonial problem, had to be solved by action in Africa itself, not by political manoeuvring in European capitals.

There were four main strands in African nationalist political ideas that came together in the 1945 Congress.

First there was the indigenous strand. African nationalism goes back to the pre-colonial period, but it received another strong manifestation in the primary resistance offered to European colonization at the very beginning of the colonial period.

The Pan-African Congress at Manchester in 1945 was part of the developing secondary resistance or 'modern' nationalism, that had begun after the First World War but was now accelerating in pace. This brand of nationalism was perhaps best exemplified, among those black nationalists who had settled in England and who dominated the Congress, by Jomo Kenyatta, 'the man from Africa', the African Personality personified, the writer of Facing Mount Kenya with impeccable roots in the African homeland.

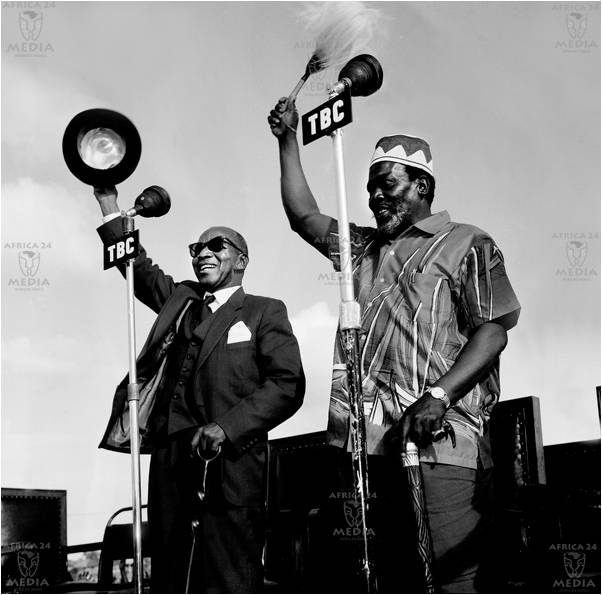

Mzee Jomo Kenyatta and Hastings Banda of Malawi

In 1934, Kenyatta enrolled at University College London and from 1935 studied

social anthropology under Bronisław Malinowski at

the London School of Economics (LSE). He was an active member of the

International African Service Bureau, a pan-Africanist, anti-colonial

organisation that had formed around former international communist leader

George Padmore, who had also become disillusioned with the Soviet Union and

himself moved to London. Kenyatta read the draft of the Kenya section of

Padmore's new book, How Britain Rules Africa (1936). He taught Gikuyu at the

University College, London and also wrote a book on the Kikuyu language in 1937

and with the editorial help of an English editor named Dinah Stock who became a

close friend, Kenyatta published his own book, Facing Mount

Kenya (his revised LSE

thesis), in 1938 under his new name, Jomo Kenyatta. The name Jomo means

"burning spear."

After the World War II, he wrote a pamphlet (with some content contributed by

Padmore), Kenya: The Land of Conflict, published by the International African

Service Bureau under the imprint Panaf Service. The Land of Conflict pamphlet

was during the gold rush in Kenya in which the land in Kakamega reserve was

being distributed to settlers, something which angered Kenyatta causing him to

speak about Britain's injustice. It is for this reason that the British dubbed

him a communist.

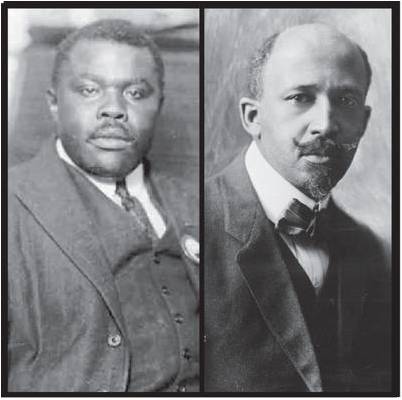

The second main strand in African nationalism was the black American racial consciousness and political discontent which had grown up under slavery and gained strength after emancipation from continued white racism an continuing economic exploitation. Black consciousness in the New World owed most to two men, Marcus Garvey and W.E.B. Du Bois. Garvey was a Jamaican who in the 1920s built up a great following in the United States through his ideas of "Africa for the Africans', or political independence, of the African Personality, or cultural regeneration, and pan-Africanism, a united African Union government, and the return of the blacks of the Diaspora to Africa.

DuBois, from the United States, organized Pan-African Congresses in the 1920s and 1930s. He was opposed to Garvey's racial exclusiveness and stressed the worldwide struggle of all oppressed, underprivileged, coloured people everywhere for freedom and Justice. The ideas of Garvey and Du Bois affected a small but important number of Africans who studied in America before the Second World War: notably Nnamdi Azikiwe of Nigeria, Kwame Nkrumah of the Gold Coast and Mbiyu Koinange of Kenya.

The third main strand was European socialism and communism, which influenced those who studied in Europe, notably Kenyatta, who joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP) in England, and Senghor and Houphouet Boigny, who were active in left wing politics in Paris, and some who studied in America, such as Nkrumah.

Chinese Chairman Mao Greeting W.E.B Du Bois

Chinese Chairman Mao Greeting W.E.B Du Bois

Communists demanded the forceful overthrow of colonial rule in the interests of 'world revolution', and believed socialism was attainable only by violent revolution. Socialists, on the other hand, favoured the advance of socialism by peaceful persuasion, through parliamentary government. Both communists and socialists were opposed to colonialism, but communists tended to favour its violent overthrow whereas socialists favoured gradual and peaceful decolonization in Africa. But African communists and socialists invariably tried to link European socialism with the socialism of African society, and were, therefore, generally undogmatic about the exact type of socialism to be applied in Africa.

The fourth strand in African nationalism in the 1940s was Gandhiism, the passive resistance principles of which were less significant to Africans than the example of mass resistance in India, and the practical effort to achieve self-determination.

African nationalism in the 1930s and 1940s was enormously stimulated by African student life in Britain, France and America. The Students made contacts with anti imperialist white liberals, socialists and communists, with West Indians and United States blacks, and conflicted with racially prejudiced whites (not just in Africa). In London alone three black organizations flourished: the. West African Students Union (WASU), founded in the 1920s by Ladipo Solanke of Nigeria; the League of Coloured People, led by the West Indian Harold Moody; and the International African Service Bureau (IASB). The IASB grew out of the IAFE or International African Friends of Ethiopia, and was dominated by those three brilliant West Indian intellectuals C.L.R. James, George Padmore and Ras Makonnen. To a considerable extent the 1945 Congress was a natural outgrowth of pan-African activity in Britain since the outbreak of the Ethiopian War.

The

Congress was largely Padmore's idea; it was organized largely by Makonnen, It

was presided over by a third West Indian, Dr Peter Milliard, a Manchester

physician, until the arrival of Du Bois from the United States. Yet in spite of

this apparent New World domination, the majority of the delegates were from

Africa, and by the end of the Congress Africans from Africa had taken over the

direction of Du Bois' movement from Africans of the Diaspora, Kwame Nkrumah,

recently arrived in Britain from the United States, by the impact of his

dynamic and brilliant personality, placed Africans in the fore front of

pan-Africanism. Kenyatta and Peter Abrahams, the South African novelist, played

quieter but significant roles.

The

Congress was largely Padmore's idea; it was organized largely by Makonnen, It

was presided over by a third West Indian, Dr Peter Milliard, a Manchester

physician, until the arrival of Du Bois from the United States. Yet in spite of

this apparent New World domination, the majority of the delegates were from

Africa, and by the end of the Congress Africans from Africa had taken over the

direction of Du Bois' movement from Africans of the Diaspora, Kwame Nkrumah,

recently arrived in Britain from the United States, by the impact of his

dynamic and brilliant personality, placed Africans in the fore front of

pan-Africanism. Kenyatta and Peter Abrahams, the South African novelist, played

quieter but significant roles.

Resolutions

The resolutions of the Congress reflect the impatience of the delegates at the gradualist approach to self-determination of the pre-war period, and the emergence of 'Africa for the Africans' as the main theme of the Congress. For example, ‘We demand for Black Africa autonomy and independence.' The demand was no longer for improvements within the colonial system. But there was a new determination to do more than just pass resolutions: 'We will fight in every way we can for freedom, democracy and social betterment.'

Many speakers argued that violence was a legitimate method of struggle against colonialism. One resolution reads:

The delegates to the fifth Pan-African Congress believe in peace. How could it be otherwise when for centuries the African peoples have been victims of violence and slavery. Yet if the western world is still determined to rule mankind by force, then Africans, as a last resort, may have to appeal to force in the effort to achieve Freedom, even if force destroys them and the world.

The struggle against imperialism in Africa was now to be fought in Africa rather than in Europe, and it was to be led by the Western-educated African elite, by men like Kenyatta, who returned to Kenya in 1946, and Nkrumah, who returned to the Gold Coast in 1947. Both men were to mobilize the African masses of their countries behind the objective of political independence, and organize mass political parties for the purpose. Indeed, this was now the pattern all over the continent.

This congress was a turning point in the history of Pan Africanism. It took place in the British city of Manchester between 15th - 19th October 1945 and was attended by over 200 delegates. Its occurrence and discussions were influenced by the following events:

1. The 1935 invasion of Ethiopia by Italy, which aroused African consciousness.

2. The defeat of Italy by Ethiopia in 1941 due to concerted efforts by Africans in Africa and the Diaspora.

3. The 1941 Atlantic charter which encouraged the colonized to fight for their independence.

4. The 2nd World War, which made African nationalists, become militant.

5. The rise of USA and U.S.S.R, which were opposed to colonialism.

6. The economic boom in Africa due to 2nd World War impact.

7. The rise and spread of communist ideas in Africa.

8. The emergence of the African elites.

9. Travels of Africans abroad where they witnessed Western democracy.

10. The advocacy for human rights by the UNO.

11. Black nationalists attended the 5th Pan African Congress from Africa, West Indies, Europe and the Caribbean.

National Movements and New States in Africa