The Angolan war of independence

The armed struggle in Angola was a natural result of the failure of peaceful protest in I960- In June the MPLA presented a petition to Lisbon appealing for a peaceful solutiontothe demand for political reform. The reply of the Portuguese government was to arrest the MPLA leaders and to have Neto publicly flogged - an act of calculated brutality designed to humiliate the ablest of the nationalist politicians.

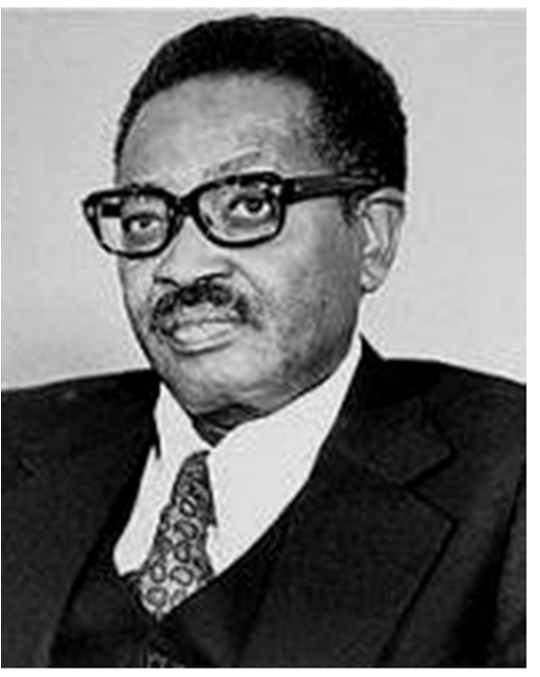

Agostinho Neto

was born in 1922 in Bengo, a small village in rural Angola, The son of a

Methodist pastor, he was one of the very few Angolan children of his generation

who had an opportunity to attend secondary school. Neto worked for a time in

the colonial health service (such as it was) and in 1947 he went to Portugal to

study medicine. His political consciousness was aroused and he wrote poems voicing

the sufferings and hopes of his people.2

Agostinho Neto

was born in 1922 in Bengo, a small village in rural Angola, The son of a

Methodist pastor, he was one of the very few Angolan children of his generation

who had an opportunity to attend secondary school. Neto worked for a time in

the colonial health service (such as it was) and in 1947 he went to Portugal to

study medicine. His political consciousness was aroused and he wrote poems voicing

the sufferings and hopes of his people.2

I live

in the dark neighbourhoods of the world

without light or life.

I go down the streets

Groping leaning on my formless dreams

stumbling in slavery in my desire to be ...

Neto joined the Portuguese Democratic Student Movement, and in 1952 he was arrested by the PIDE. He completed his medical studies in prison between 1955 and 1957. Neto qualified as a doctor in 1958 and returned to Angola the following year. He Joined the MPLA, of which he soon became the leader. After the I960 petition, his arrest and his flogging he was imprisoned first on the Cape Verde Islands and later in Lisbon.

After Neto's

arrest in Angola the MPLA arranged a peaceful demonstration at Catete to ask

for his release. The police opened fire and killed 30 people, and killed or

arrested everyone in Bengo before destroying the village, and then launched a

wave of terror against those locations in Luanda, the capital, where the MPLA

had support. Clearly, the Portuguese in Angola drove the Africans to the use of

force.

In 1961 the Angolan revolution or War of Independence began. It took the form of three separate armed risings.

The first rising began in January in Malange district in the north-east. It grew out of a strike by cotton workers following a fall in cotton prices and the failure to pay them. The Portuguese reacted to the strike with mass arrests and the cotton workers reacted to the arrests with an armed uprising, making attacks on Portuguese property rather than on people. The Malange rising has been called Maria's War because Antonio Mariano, the leader of the Maria messianic cult, and his followers joined in the struggle. The Portuguese crushed the rising in February by bombing villages and sending in infantry against the survivors. Thousands of villagers, mostly unarmed, were killed. Mariano was captured and he died under torture in a Portuguese prison.

Maria's War encouraged the Marxist MPLA to act and start a second rising. Early in the morning of 4 June several hundred MPLA freedom fighters attacked Luanda's main political prison. Seven Portuguese police were killed and some prisoners were freed, but forty MPLA men were machine-gunned and the prison was not captured. The MPLA also made unsuccessful attacks on the radio station and a military barracks. On 6 June the MPLA forces in Luanda either died fighting, surrendered or fled. European settler mobs rampaged through the city's shanty towns, killing thousands of Africans and mestizos. The killers were protected by the police.

Maria's War had been inspired partly by religion, and the MPLA rising by Marxism. The third rising, that of the Bakongo people of northern Angola that started on 15 March, was inspired partly by ethnic feeling, by the confused desire of the Bakongo to resurrect their ancient kingdom and/ or to join their Bakongo kin in newly independent Zaire. The Bakongo rising was also provoked by the conditions of the coffee-plantation workers in Primavera, whose initial revolt spread all over the north. The leadership of this rising was hastily assumed by the Angola People's Union (UFA) an ethnically based party which - mobilized the Bakongo in attacks on Africans of other ethnic groups as well as on mestizos and Portuguese..

HOLDEN ROBERTO, leader of NFLA unsuccessfully used white mercenaries to install him; when things failed he went to exile. He died in 2007.

The UPA-led rebels killed about a thousand Portuguese soldiers and about three hundred Portuguese civilians in the first weeks of the rising. The poorly armed, scarcely disciplined rebels managed by force of numbers to drive the white population into a retreat behind fortified defences in the towns. For a time the Portuguese abandoned control of northern Angola. In July, however, the Portuguese launched a prepared and systematic counter-massacre, with cold calculation raining napalm bombs on villages in order to terrorize the people into submission. A force of 25 000 Portuguese troops was reinforced by auxiliary forces of white settlers whose aim was not 50 much re- . establishment of control as vengeance.

In recapturing most of the north the Portuguese killed at least 20 000, and forced about 350 000 Africans to abandon their homes and become refugees in Zaire. Perhaps another 150 000 had already fled to Zaire from Malange after Maria's War.

At the end of 1961 the Portuguese had effectively defeated the armed risings in Angola. Over the whole country the Portuguese deployed 140 000 troops (of whom 100 000 were - Africans), which pinned down the surviving UFA fighters to isolated pockets of thinly populated mountain areas and forest regions. The nationalists had not only failed to unite but seemed to have no contact with each other. An uphill struggle was to face the freedom fighters for the rest of the 1960s. They did not make their task any easier by developing three rival parties: the FNLA, the MPLA and UNITA.

Holden Roberto, the UPA leader, reorganized his party in 1962 into the FNLA (National Front for the Liberation of Angola), with headquarters in Kinshasa and guerilla training camps near the city. Also in 1962 the FNLA formed a government in exile (GRAE) in Kinshasa. GRAE claimed to represent all the peoples of Angola, though in reality it was acceptable only to the Bakongo. The FNLA received a boost in October 1965 when General Mobutu overthrew Tshombe in Kinshasa. Like Roberto, Mobutu was a Mukongo, and pro-Western. Mobutu gave the FNLA considerable assistance and encouraged it to open up a front in eastern Angola which it did in 1966. Roberto, however, failed to make the most of this opportunity. He wanted to fight the Portuguese in the style of 2.^0 facto government (in exile), with the guerillas acting as its military arm. A gulf emerged between the FNLA/GRAE political leadership in Kinshasa and its guerillas in the forests of Angola.

Unlike the FNLA, the MPLA was much more broadly based, much more committed to the armed struggle, and a movement in which the political and military wings were fused instead of being loosely linked. In 1962 Neto escaped from detention in Portugal and made his way to Morocco, and from there to Zaire. The MPLA also set up its headquarters ; in exile in Kinshasa. It received its support from the Western-educated elite all over the country, whether African or mestizo; it did not rely on an ethnic base of support. An avowed socialist party, the MPLA received aid from the Soviet Union, mainly in the form 's- of guerilla training and weapons. The FNLA received aid from the United States, mainly money channelled through the CIA. In 1964 the MPLA launched a guerilla offensive in, the Cabinda enclave, operating from bases in Congo-Brazzaville and in Cabinda itself. However, the MPLA achieved little success in Cabinda. It had to contend with the rivalry of FLEC, a Cabinda separatist movement. The area was too small for guerillas to operate in, to easily, unlike the vast expanses of eastern Angola. Moreover, the Portuguese poured in extra troops in their determinationtodefend the oil installations of the Cabinda Gulf Oil Company (US).

In 1965 Mobutu expelled the MPLA from Kinshasa. The MPLA set up a new headquarters across the river in Brazzaville. In 1967 the MPLA made an important change of strategy, deciding to concentrate on eastern Angola and to open up a new front there on the border with Zambia. From its bases in Zambia the MPLA began to win more success. Operating on classic guerilla principles of the people-in arms with the government and guerillas as one, the beginnings of liberated zones began to appear. Senior MPLA officers moved from Brazzaville to Lusaka and training camps were set up in Zambia and Tanzania. Early in 1968 the MPLA established a new headquarters near Teixeira de Sousa, a border post on the Benguela railway at the Zaire border. By 1970 the MPLA was receiving more aid from the African Liberation Committee of the OAU than was GRAE/FNLA, on top of its considerable assistance from the USSR and its East European satellites. The MPLA had indeed made progress from an urban-based predominantly mestizo intellectual group to a functioning guerilla force. However, the MPLA had failed in two respects. First, it failed even as late as 1974 to establish effective, liberated zones, its headquarters remaining outside the country, in Lusaka.

Secondly, like the FNLA, it was unprepared to consider unity except on its own terms and persisted in trying to liberate Angola on its own. It waged war in eastern Angola not only on the Portuguese but on guerillas of rival FNLA and UNITA and made no attempt to form a working relationship with these two parties. The MPLA's major success was to win its own civil war when one of its leaders, Daniel Chipenda, made an abortive bid for power in the party in 1973-4 by attempting to rouse the ethnic consciousness of the Ovimbundu people.

UNITA (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola) was founded in 1966 by Jonas Savimbi, GRAE' s former foreign minister, as a breakaway group from the FNLA. Savimbi opposed Roberto's Bakongo ethnicism, but he found it difficult to win support outside the Ovimbundu people (who live in the hinterland of Benguela). UNITA began guerilla operations from Zambia, but soon set up several bases inside Angola. In August 1967 the Zambian Government expelled UNITA after ii attacked the Benguela railway that carried Zambia's copper to the Atlantic.

Ironically the expulsion drove UNITA to, strengthen itself inside Angola. In December it fought major clashes with the Portuguese near Luso. Savimbi had some military success partly because, like Neto, he waged a people's war. Savimbi claimed to be pro-Chinese, but he was interested more in Chinese .military aid than ideology. Savimbi also had links with the CIA.

At the time of the Lisbon coup in 1974 the Portuguese could be said to have contained the nationalist guerillas in Angola. Sectarianism, infighting and open warfare between the rival parties in eastern Angola had served as a substitute for effective struggle against the Portuguese. The hard fact remains that from 1961 to 1974 the Portuguese were able to safeguard increased Western investment in diamond and manganese mining in the interior. Angola more than Guinea and Mozambique needed the Lisbon coup before independence could be gained. Independence came on 11 November 1975, when a " transitional government was formed of the three rival factions. By then the vast majority of Angola's 20.000 white settlers had left the country, only 10-15 000 remaining. The stage was set for the Angolan Civil War.

Former rebel leader Jonas Savimbi of Angola survived in the bush for over thirty years due the support from the Western bloc and other developed countries.

National Movements and New States in Africa