Causes of the Italo-Ethiopian War

The war was caused by two major factors among others : a revival of Italian imperialism; and the weakness of the League of Nations - a weakness that encouraged that imperialism.

The Italian desire to revenge against Ethiopia

In 1896 the Italians were defeated by the then strong, well-trained, organised and patriotic Ethiopian forces under Emperor Menelik II. Italy wanted revenge for Adowa, which had stamped her as a nation without martial valour. She had entered the First World War hoping to restore her military reputation, but again put up a poor performance on the battlefield and consequently gained no reward when the German colonies in Africa were shared out among the victors at the Treaty of Versailles in 1919.

The coup of 1922, which put Benito Mussolini and his Fascist Party in power, led to a transformation of Italy and a revival of Italian imperial expansion. Fascism was a doctrine peculiarly suited to colonialism, because it espoused the principle of the survival of the fittest in politics, which legitimized the expansion of stronger races at the expense of weaker ones.

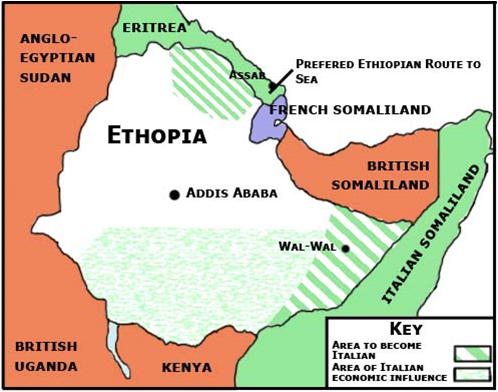

Italy had come late to the Partition of Africa and had consequently got little, and even that was only desert and semi-desert: Eritrea, Somaliland and Libya. She had long covered Ethiopia, with its cool climate and rich agricultural soils, and hoped to link her Eritrean and Somali possessions by conquering the ancient highland kingdom and creating a united Italian East African Empire.

Mussolini just wanted to revenge.

Mussolini just wanted to revenge.

Mussolini was determined to invade Ethiopia, and spent many years reorganizing and equipping the Italian army for that task. But it is doubtful if he would have gone ahead with the invasion if the League of Nations had made a serious attempt to stop him.

Britain and France were the major powers of the League, which was set up after the First World War to unite the nations of the world and avoid another world war. But the United States, in a mood of isolationism, had refused to join, and Germany, now under the Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler, had left the League. Britain and France in 1935 were fearful of a rearming Germany under Hitler, and allowed their fear to dictate their policy over Ethiopia. They calculated that if they prevented Italian aggression in Ethiopia.

Mussolini would be driven into the arms of his fellow right-wing dictator in Germany. Therefore, the two major West European democracies decided to appease Italy in order to keep on good terms with her on the European continent. This meant they had to ignore their obligations to the Covenant of the League and abandon Ethiopia, one of the League's member states. Britain and France were far more obsessed with their own endangered security in Europe than they were with the security of the Empire of Ethiopia.

Franco-British appeasement of Italy first took the form of refusal to supply arms to Ethiopia for its own defence. As Italy steadily massed troops and stockpiled supplies in Eritrea and Somaliland in 1934 and early 1935, Haile Selassie attempted to buy modern weapons from Europe to resist the coming invasion. Yet Britain and France responded by placing an embargo on the sale of arms to both potential belligerents. This, of course, clearly favoured Italy (as it was secretly meant to do), since Italy was quite capable of supplying its own arms requirements and Ethiopia was not. In effect, then, the embargo applied only to Ethiopia. This hypocritical immorality on the part of Britain and France - the refusal to supply arms to the victim of an aggressor - ensured that the Italian invasion would encounter weak resistance.

The second form of appeasement took place after the invasion began. The League of Nations imposed sanctions on the aggressor, whereby member states were forbidden to trade with Italy in a wide range of products. The sanctions were predictably half-hearted, and excluded the vital commodity - oil - which was essential for modern military operations and for the success of the Italian invasion. The sanctions did not halt the Italian advance by as much as a single day.

The third form of appeasement was the notorious Hoare-Laval Pact of December 1935, in which the British Foreign Secretary, Sir Samuel Hoare, and the French Foreign Minister, Pierre Laval, proposed a plan to halt the war by partitioning Ethiopia, giving part of the north of the country to Italy and allowing the Emperor to keep the south. The Pact was destroyed by the power of British public opinion, subject to one of its periodical fits of morality, and Hoare was forced to resign.1 Yet the Hoare-Laval plan was proposed while the Ethiopian army was still intact and Italian victory was not absolutely certain. Hoare's plan, though immoral, offered more help to the Ethiopians than the British public could offer, which was generous but ineffective moral support.

The British public acquiesced in the fourth form of appeasement of Italy over Ethiopia: its government's recognition in 1938 of the Italian conquest of the whole of Ethiopia. By then the British public was more concerned with the fate of the Czechs of Central Europe.

The casus belli for the Italo-Ethiopian War arose out of the Wal-Wal Incident of 1934. An Italian force had occupied the settlement of Wal-Wal just inside Ethiopia on the border with Italian Somaliland, in largely unsurveyed desert. The local Ethiopian commander attacked the Italian force with his men, but was driven off. Haile Selassie suggested international arbitration, but this was rejected by Italy, which demanded an apology and a large indemnity, which Ethiopia naturally refused to pay. Mussolini used this refusal as an excuse for war.

The casus belli for the Italo-Ethiopian War arose out of the Wal-Wal Incident of 1934. An Italian force had occupied the settlement of Wal-Wal just inside Ethiopia on the border with Italian Somaliland, in largely unsurveyed desert. The local Ethiopian commander attacked the Italian force with his men, but was driven off. Haile Selassie suggested international arbitration, but this was rejected by Italy, which demanded an apology and a large indemnity, which Ethiopia naturally refused to pay. Mussolini used this refusal as an excuse for war.

The renewal of Italian imperialism: In past years, the glory of Italy had engulfed parts of Europe, Asia, Middle East and North Africa.

Italy wanted to prove her military worth to fellow European powers.

Italy had entered the colonial field very late and had obtained a very small share of the African continent while her counterparts especially Britain and France has obtained a lion's share

The unfairness of the 1919 Versailles treaty: After the 1st world war the victorious powers shared out the colonies of defeated Germany.

The rise of Benedicto Mussolini and his fascist party to power in Italy in 1922 also explains the 1935 invasion of Ethiopia.

Italy's desire to civilise Ethiopia: She claimed that her attack on Ethiopia was aimed at spreading Christianity, ending the primitive feudalism in Ethiopia, ending slave trade, spreading European progress and democracy in Africa.

Expected help from the axis power: The axis pact/alliance between Mussolini of Italy, Hitler of Germany and Hirohito of Japan (1926-1989) assured Mussolini of support.

Expected help from the axis power: The axis pact/alliance between Mussolini of Italy, Hitler of Germany and Hirohito of Japan (1926-1989) assured Mussolini of support.

Emperor in Exile

Economic consideration made Italy to invade Ethiopia in 1935. Firstly the Ethiopian highlands were fertile and conducive for the white man's settlement and agriculture. Secondly Italy had been adversely affected by the 1929-32 world depression, which brought about unemployment, scarcity inflation and raising of taxes. Mussolini hoped to solve these problems and restore his personal popularity by colonising Ethiopia.

Desire to control port of Massawa: Since time immemorial, this Red Sea port had played a leading role in the profitable trade between Europe, Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

The failure to drive the Italians out of Eritrea also led to the crisis. After the 1896 Adowa victory, the Italians took refugee in Eritrea, which was by then a province of Ethiopia.

The Italian fear that Ethiopia intended to expel Italians out of Eritrea and Somali land contributed to its invasion in 1935.

The desire to create a United Italian East African Empire led to the invasion of Ethiopia.

The Divisions prevailing in Ethiopia encouraged the Italians to invade Ethiopia. The unity, which had characterised Ethiopia at the time of the 1896 Adowa war, had vanished.

The Anglo-French conspiracy against Ethiopia also led to the invasion. The British and Fresh were aware that Italy was re-arming but didn't want her to test her poisonous weapons on European soil.

The example of Japanese imperialism in China in 1931 and 1933 catalysed Italy's plans to invade Ethiopia. In September 1931 Japan attacked China and occupied Manchuria province.

The unfair arms-embargo imposed by Britain and France. In the early years of the 1930s, it became clear that relations between Ethiopia and Italy were diminishing.

Ethiopia attacked out of envy. It is true that Ethiopia had survived the 19th Century European colonialism and that Africans regarded Ethiopia as a pride of Africa.

The upsurge of African nationalism all over Africa and in the Diaspora also explains the crisis.

Mussolini had full support from the Italian public opinion.

1 Jomo Kenyatta was one of the speakers at a big rally held in Trafalgar Square, London, to condemn the Hoare-Laval plan. During his speech he satirized Hoare in devastating fashion: 'Sir Samuel Hoare . . .You wonder about him? Well, what else can you expect from a whore. A whore'-s a whore. He will buy anything, sell anything.' (See Ras Makonnen, Pan-Africanism from Within, Oxford University Press, 1973.)

National Movements and New States in Africa