The Coming of the Foreigners

At the tip of the continent the British found an established colony with 25,000 slaves, 20,000 white colonists, 15,000 Khoisan, and 1,000 freed black slaves. Power resided solely with a white élite in Cape Town, and differentiation on the basis of race was deeply entrenched. Outside Cape Town and the immediate hinterland, isolated black and white pastoralists populated the country.

Like the Dutch before them, the British initially had little interest in the Cape Colony, other than as a strategically located port. As one of their first tasks they tried to resolve a troublesome border dispute between the Boers and the Xhosa on the colony's eastern frontier. In 1820 the British authorities persuaded about 5,000 middle-class British immigrants (most of them "in trade") to leave England behind and settle on tracts of land between the feuding groups with the idea of providing a buffer zone. The plan was singularly unsuccessful. Within three years, almost half of these 1820 Settlers had retreated to the towns, notably Grahamstown and Port Elizabeth, to pursue the jobs they had held in Britain.

While doing nothing to resolve the border dispute, this influx of settlers solidified the British presence in the area, thus fracturing the relative unity of white South Africa. Where the Boers and their ideas had before gone largely unchallenged, European Southern Africa now had two language groups and two cultures. A pattern soon emerged whereby English-speakers became highly urbanised, and dominated politics, trade, finance, mining, and manufacturing, while the largely uneducated Boers were relegated to their farms.

The gap between the British settlers and the Boers further widened with the abolition of slavery in 1833, a move that the Boers generally regarded as against the God-given ordering of the races. Yet the British settlers' conservatism and sense of racial superiority stopped any radical social reforms, and in 1841 the authorities passed a Masters and Servants Ordinance, which perpetuated white control. Meanwhile, British numbers increased rapidly in Cape Town, in the area east of the Cape Colony (present-day Eastern Cape Province), in Natal and, after the discovery of gold and diamonds, in parts of the Transvaal, mainly around present-day Gauteng.

Difaqane and destruction

Shaka Zulu in traditional Zulu military garb.

The early 19th century saw a time of immense upheaval relating to the military expansion of the Zulu kingdom. Sotho-speakers know this period as the difaqane ("forced migration"); while Zulu-speakers call it the mfecane ("crushing").

The full causes of the difaqane remain in dispute, although certain factors stand out. The rise of a unified Zulu kingdom had particular significance. In the early 19th century, Nguni tribes in KwaZulu-Natal began to shift from a loosely-organised collection of kingdoms into a centralised, militaristic state. Shaka Zulu, son of the chief of the small Zulu clan, became the driving force behind this shift. At first something of an outcast, Shaka proved himself in battle and gradually succeeded in consolidating power in his own hands. He built large armies, breaking from clan tradition by placing the armies under the control of his own officers rather than of the hereditary chiefs. Shaka then set out on a massive programme of expansion, killing or enslaving those who resisted in the territories he conquered. His impis (warrior regiments) were rigorously disciplined: failure in battle meant death.

Peoples in the path of Shaka's armies moved out of his way, becoming in their turn aggressors against their neighbours. This wave of displacement spread throughout Southern Africa and beyond. It also accelerated the formation of several states, notably those of the Sotho (present-day Lesotho) and of the Swazi (now Swaziland).

In 1828 Shaka was killed by his half-brothers Dingaan and Umthlangana. The weaker and less-skilled Dingaan became king, relaxing military discipline while continuing the despotism. Dingaan also attempted to establish relations with the British traders on the Natal coast, but events had started to unfold that would see the demise of Zulu independence.

The Great Trek

Meanwhile, the Boers had started to grow increasingly dissatisfied with British rule in the Cape Colony. The British proclamation of the inequality of the races particularly angered them. Beginning in 1835, several groups of Boers, together with large numbers of Khoikhoi and black servants, decided to trek off into the interior in search of greater independence. North and east of the Orange River (which formed the Cape Colony's frontier) these Boers or Voortrekkers ("Pioneers") found vast tracts of apparently uninhabited grazing lands. They had, it seemed, entered their promised land, with space enough for their cattle to graze and their culture of anti-urban independence to flourish. Little did they know that what they found - deserted pasture lands, disorganised bands of refugees, and tales of brutality - resulted from the difaqane, rather than representing the normal state of affairs.

With the exception of the more powerful Ndebele, the Voortrekkers encountered little resistance among the scattered peoples of the plains. The difaqanefirearms. Their weakened condition also solidified the Boers' belief that European occupation meant the coming of civilisation to a savage land. However, the mountains where King Moshoeshoe I had started to forge the Basotho nation that would later become Lesotho and the wooded valleys of Zululand proved a more difficult proposition. Here the Boers met strong resistance, and their incursions set off a series of skirmishes, squabbles, and flimsy treaties that would litter the next 50 years of increasing white domination. had dispersed them, and the remnants lacked horses and

British vs. Boers vs. Zulus

Indians arriving in Durban for the first time.

The Great Trek first halted at Thaba Nchu, near present-day Bloemfontein, where the trekkers established a republic. Following disagreements among their leadership, the various Voortrekker groups split apart. While some headed north, most crossed the Drakensberg into Natal with the idea of establishing a republic there. Since the Zulus controlled this territory, the Voortrekker leader Piet Retief paid a visit to King Dingaan, where the suspicious Zulu promptly killed him. This killing triggered other attacks by Zulus on the Boer population, and a revenge attack by the Boers. The culmination came on 16 December1838, in the Battle of Blood River, fought at the Ncome River in Natal. Though several Boers suffered injuries, they killed several thousand Zulus, reportedly causing the Ncome's waters to run red.

Zulu warriors, late 19th century

After this victory, which resulted from the possession of superior weapons, the Boers felt that their expansion really did have a long suspected stamp of divine approval. Yet their hopes for establishing a Natal republic remained short lived. The British annexed the area in 1843, and founded their new Natal colony at present-day Durban. Most of the Boers, feeling increasingly squeezed between the British on one side and the native African populations on the other, headed north.

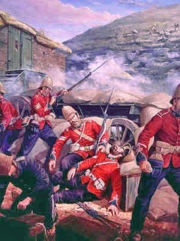

British casualties fighting against the Zulus at The Battle of Rorke's Drift during the Anglo-Zulu Wars

The British set about establishing large sugar plantations in Natal, but found few inhabitants of the neighbouring Zulu areas willing to provide labour. The British confronted stiff resistance to their encroachments from the Zulus, a nation with well-established traditions of waging war, who inflicted one of the most humiliating defeats on the British army at the Battle of Isandlwana in 1879, where over 1400 British soldiers were killed. During the ongoing Anglo-Zulu Wars, the British eventually established their control over what was then named Zululand, and is today known as Natal.

The British turned to India to resolve their labour shortage, as Zulu men refused to adopt the servile position of labourers and in 1860 the SS Truro arrived in Durban harbour with over 300 people on board. Over the next 50 years, 150,000 more indentured Indians arrived, as well as numerous free "passenger Indians", building the base for what would become the largest Indian community outside of India. As early as 1893, when Mahatma Gandhi arrived in Durban, Indians outnumbered whites in Natal. (See Asians in South Africa.)

Growth of independent South Africa

The Boer republics

South African Republic and Orange Free State

The farm outside of Johannesburg on the Witwatersrand - site of the first discovery of gold in 1886.

The Boers meanwhile persevered with their search for land and freedom, ultimately establishing themselves in the Transvaal and in the Orange Free State. For a while it seemed that these republics would develop into stable states, despite having thinly-spread populations of fiercely independent Boers, no industry, and minimal agriculture. The discovery of diamonds near Kimberley turned the Boers' world on its head (1869). The first diamonds came from land belonging to the Griqua, but to which both the Transvaal and Orange Free State laid claim. Britain quickly stepped in and resolved the issue by annexing the area for itself.

The discovery of the Kimberley diamond-mines unleashed a flood of European and black labourers into the area. Towns sprang up in which the inhabitants ignored the "proper" separation of whites and blacks, and the Boers expressed anger that their impoverished republics had missed out on the economic benefits of the mines.

The Anglo-Boer Wars: Boer Wars

The Relief of Ladysmith. Sir George White greets Major Hubert Gough on 28 February. Painting by John Henry Frederick Bacon (1868-1914)

Boer women and children in a concentration camp.

First Anglo-Boer War

Long-standing Boer resentment turned into full-blown rebellion in the Transvaal (under British control from 1877), and the first Anglo-Boer War, known to Afrikaners as the "War of Independence", broke out in 1880. The conflict ended almost as soon as it began with a crushing Boer victory at Battle of Majuba Hill (27 February 1881). The republic regained its independence as the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek ("South African Republic"), or ZAR. Paul Kruger, one of the leaders of the uprising, became President of the ZAR in 1883. Meanwhile, the British, who viewed their defeat at Majuba as an aberration, forged ahead with their desire to federate the Southern African colonies and republics. They saw this as the best way to come to terms with the fact of a white Afrikaner majority, as well as to promote their larger strategic interests in the area.

Inter-war period

In 1879, Zululand came under British control. Then in 1886, an Australian prospector discovered gold in the Witwatersrand, accelerating the federation process and dealing the Boers yet another blow. Johannesburg's population exploded to about 100,000 by the mid-1890s, and the ZAR suddenly found itself hosting thousands of uitlanders, both black and white, with the Boers squeezed to the sidelines. The influx of Black labour in particular worried the Boers, many of whom suffered economic hardship and resented the black wage-earners.

The enormous wealth of the mines, largely controlled by European "Randlords", soon became irresistible for British imperialists. In 1895, a group of renegades led by Captain Leander Starr Jameson entered the ZAR with the intention of sparking an uprising on the Witwatersrand and installing a British administration. This incursion became known as the Jameson Raid. The scheme ended in fiasco, but it seemed obvious to Kruger that it had at least the tacit approval of the Cape Colony government, and that his republic faced danger. He reacted by forming an alliance with Orange Free State.

Second Anglo-Boer War

Main article: Second Boer War

Boer guerillas during the Second Boer War.

The situation peaked in 1899, when the British demanded voting rights for the 60,000 foreign whites on the Witwatersrand. Until that point, Kruger's government had excluded all foreigners from the franchise. Kruger rejected the British demand and called for the withdrawal of British troops from the ZAR's borders. When the British refused, Kruger declared war. This Second Anglo-Boer War lasted longer, and the British preparedness surpassed that of Majuba Hill. By June 1900, Pretoria, the last of the major Boer towns, had surrendered. Yet resistance by Boer bittereinders continued for two more years with guerrilla-style battles, which the British met in turn with scorched earth tactics. By 1902 26,000 Boers had died of disease and neglect in concentration camps. On 31 May 1902 a superficial peace came with the signing of the Treaty of Vereeniging. Under its terms, the Boer republics acknowledged British sovereignty, while the British in turn committed themselves to reconstruction of the areas under their control.

Roots of union

Johannesburg around 1890

During the immediate post-war years the British focussed their attention on rebuilding the country, in particular the mining industry. By 1907 the mines of the Witwatersrand produced almost one-third of the world's annual gold production. But the peace brought by the treaty remained fragile and challenged on all sides. The Afrikaners found themselves in the ignominious position of poor farmers in a country where big mining ventures and foreign capitalworkplaceAfrikaans as the volkstaal ("people's language") and as a symbol of Afrikaner nationhood. Several nationalist organisations sprang up. rendered them irrelevant. Britain's unsuccessful attempts to anglicise them, and to impose English as the official language in schools and the particularly incensed them. Partly as a backlash to this, the Boers came to see

The system left Blacks and Coloureds completely marginalised. The authorities imposed harsh taxes and reduced wages, while the British caretaker administrator encouraged the immigration of thousands of Chinese to undercut any resistance. Resentment exploded in the Bambatha Rebellion of 1906, in which 4,000 Zulus lost their lives after protesting against onerous tax legislation.

The British meanwhile moved ahead with their plans for union. After several years of negotiations, the South Africa Act 1909 brought the colonies and republics - Cape Colony, Natal, Transvaal, and Orange Free State - together as the Union of South Africa. Under the provisions of the act, the Union remained British territory, but with home-rule for Afrikaners. The British High Commission territories of Basutoland (now Lesotho), Bechuanaland (now Botswana), Swaziland, and Rhodesia (now Zambia and Zimbabwe) continued under direct rule from Britain.

English and Dutch became the official languages. Afrikaans did not gain recognition as an official language until 1925. Despite a major campaign by Blacks and Coloureds, the voter franchise remained as in the pre-Union republics and colonies, and only whites could gain election to parliament.

1910 Union of South Africa

In 1910 the Union of South Africa was created by the unification of four areas, by joining the two former independent Boer republics of the South African Republic (Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek) and the Orange Free State (Oranje Vrystaat) with the the British dominated Cape Province and Natal. Most significantly, the new Union of South Africa gained international respect with British Dominion status putting it on par with three other important British dominions and allies: Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

World War I

Bonds with the British Empire

During the First World War, Smuts (right) and Botha were key members of the British Imperial War Cabinet.

The Union of South Africa was tied closely to the British Empire, and automatically joined with Great Britain and the allies against the German Empire. Both Prime Minister Louis Botha and Defence Minister Jan Smuts, both former Second Boer War generals who had fought against the British then, but who now became active and respected members of the Imperial War Cabinet. (See Jan Smuts during World War I.)

South Africa was part of significant military operations against Germany. In spite of Boer resistance at home, the Afrikaner-led government of Louis BothaAllies of World War I and fought alongside its armies. The South African Government agreed to the withdrawal of British Army units so that they were free to join the European war, and laid plans to invade German South-West Africa. Elements of the South African army refused to fight against the Germans and along with other opponents of the Government rose in open revolt. The government declared martial law on 14 October 1914, and forces loyal to the government under the command of General Louis Botha and Jan Smuts proceeded to destroy the Maritz Rebellion. The leading Boer rebels got off lightly with terms of imprisonment of six and seven years and heavy fines. (See World War I and the Maritz Rebellion.) unhestitatingly joined the side of the

Military action against Germany during World War I

The South African Union Defence Force saw action in a number of areas:

- It dispatched its army to German South-West Africa (later known as South West Africa and now known as Namibia). The South Africans expelled German forces and gained control of the former German colony. (See German South-West Africa in World War I.)

- A military expedition under General Jan Smuts was dispatched to German East Africa (later known as Tanganyika and now known as Tanzania). The objective was to fight German forces in that colony and to try to capture the elusive German General von Lettow-Vorbeck. Ultimately, Lettow-Vorbeck fought his tiny force out of German East Africa into Mozambique, where he surrendered a few weeks after the end of the war. (See German East Africa in First World War.)

- 1st South African Brigade troops were shipped to France to fight on the Western Front. The most costly battle that the South African forces on the Western Front fought in was the Battle of Delville Wood in 1916. (See South African Army in World War I.)

- South Africans also saw action with the Cape Corps as part of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force in Palestine. (See Cape Corps 1915 - 1991)

Military contributions and casualties in World War I

More than 146,000 whites, 83,000 blacks and 2,500 people of mixed race ("Coloureds") and Asians served in South African military units during the war, including 43,000 in German South-West Africa and 30,000 on the Western Front. An estimated 3,000 South Africans also joined the Royal Flying Corps. The total South African casualties during the war was about 18,600 with over 12,452 killed - more than 4,600 in the European theater alone.

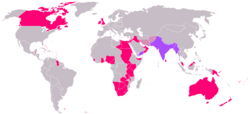

The British Empire is red on the map, at its zenith in 1919. (India highlighted in purple.) South Africa, bottom center, lies between both halves of the Empire.

There is no question that South Africa greatly assisted the Allies, and Great Britain in particular, in capturing the two German colonies of German-West-Africa and German-East-Africa as well as in battles in Western Europe and the Middle East. South Africa's ports and harbors, such as at Cape Town, Durban, and Simon's Town, were also important rest-stops, refueling-stations, and served as strategic assets to the British Royal Navy during the war, helping to keep the vital sea lanes to the British Raj open.

World War II

Political choices at outbreak of war

On the eve of World War II the Union of South Africa found itself in a unique political and military quandary. While it was closely allied with Great Britain, being a co-equal Dominion under the 1931 Statute of Westminster with its head of state being the British king, the South African Prime Minister on September 1, 1939 was none other than Barry Hertzog the leader of the pro-Afrikaner anti-British National party that had joined in a unity government as the United Party.

Herzog's problem was that South Africa was constitutionally obligated to support Great Britain against Nazi Germany. The Polish-British Common Defence Pact obligated Britain, and in turn its dominions, to help Poland if attacked by the Nazis. After Hitler's forces attacked Poland on the night of August 31, 1939, Britain declared war on Germany within a few days. A short but furious debate unfolded in South Africa, especially in the halls of power in the Parliament of South Africa, that pitted those who sought to enter the war on Britain's side, led by the pro-Allied, pro-British Afrikaner, ex-General, and former Prime Minister Jan Smuts against then-current Prime Minister Barry Hertzog who wished to keep South Africa "neutral", if not pro-Axis.

Declaration of war against the Axis

B. J. Vorster, member of Ossewabrandwag, imprisoned during WWII. Later became Prime Minister of South Africa, and briefly its President.

On September 4, 1939, the United Party caucus refused to accept Hertzog's stance of neutrality in World War II and deposed him in favor of Smuts. Upon becoming Prime Minister of South Africa, Smuts declared South Africa officially at war with Germany and the Axis. Smuts immediately set about fortifying South Africa against any possible German sea invasion because of South Africa's global strategic importance controlling the long sea route around the Cape of Good Hope.

Smuts took severe action against the pro-Nazi South African Ossewabrandwag movement (they were caught committing acts of sabotage) and jailed its leaders for the duration of the war. (One of them, John Vorster, was to become future Prime Minister of South Africa.) (See Jan Smuts during World War II.)

Prime Minister and Field Marshal Smuts

Prime Minister Jan Smuts was the only important non-British general whose advice was constantly sought by Britain's war-time Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Smuts was invited to the Imperial War Cabinet in 1939 as the most senior South African in favour of war. In 28 May 1941, Smuts was appointed a Field Marshal of the British Army, becoming the first South African to hold that rank. Ultimately, Smuts would pay a steep political price for his closeness to the British establishment, to the King, and to Churchill which had made Smuts very unpopular among the conservative nationalistic Afrikaners, leading to his eventual downfall, whereas most English-speaking whites and a minority of liberal Afrikaners in South Africa remained loyal to him. (See Jan Smuts during World War II.)

Military contributions and casualties in World War II

South Africa and its military forces contributed in many theaters of war. South Africa's contribution consisted mainly of supplying troops, men and material for the North African campaign (the Desert War) and the Italian Campaign as well as to Allied ships that docked at its crucial ports adjoining the Atlantic Ocean and Indian Ocean that converge at the tip of Southern Africa. Numerous volunteers also flew for the Royal Air Force. (See: South African Army in World War II; South African Air Force in World War II; South African Navy in World War II; South Africa's contribution in World War II.)

- The South African Army and Air Force helped defeat the Italian army of the Fascist Benito Mussolini that had invaded Abyssinia (now known as Ethiopia) in 1935. During the 1941 East African Campaign South African forces made important contribution to this early Allied victory.

- Another important victory that the South African's participated in was the liberation of Malagasy (now known as Madagascar) from the control of the Vichy French who were allies of the Nazis. British troops aided by South African soldiers, staged their attack from South Africa, occupied the strategic island in 1942 to preclude its seizure by the Japanese.

- The South African 1st Infantry Division took part in several actions in North Africa in 1941 and 1942, including the Battle of El Alamein, before being withdrawn to South Africa.

- The South African 2nd Infantry Division also took part in a number of actions in North Africa during 1942, but on 21 June 1942 two complete infantry brigades of the division as well as most of the supporting units were captured at the fall of Tobruk.

- The South African 3rd Infantry Division never took an active part in any battles but instead organised and trained the South African home defence forces, performed garrison duties and supplied replacements for the South African 1st Infantry Division and the South African 2nd Infantry Division. However, one of this division's constituent brigades - 7 SA Motorised Brigade - did take part in the invasion of Madagascar in 1942.

- The South African 6th Armoured Division fought in numerous actions in Italy from 1944 to 1945.

- South Africa contributed to the war effort against Japan, supplying men and manning ships in naval engagements against the Japanese. [1]

Of the 334,000 men volunteered for full time service in the South African Army during the war (including some 211,000 whites, 77,000 blacks and 46,000 "coloureds" and Asians), nearly 9,000 were killed in action.

Aftermath of World War II

South Africa emerged from the Allied victory with its prestige and national honor enhanced as it had fought tirelessly for the Western Allies. South Africa's standing in the international community was rising, at a time when the Third World's struggle against colonialism had still not taken center stage. In May 1945, Prime Minister Smuts represented South Africa in San Francisco at the drafting of the United Nations Charter. Just as he did in 1919, Smuts urged the delegates to create a powerful international body to preserve peace; he was determined that, unlike the League of Nations, the United Nations would have teeth. Smuts signed the Paris Peace Treaty, resolving the peace in Europe, thus becoming the only signatory of both the treaty ending the First World War, and that ending the Second.

However, internal political struggles in the disgruntled and essentially impoverished Afrikaner community would soon come to the fore leading to Smuts' defeat at the polls in the 1948 elections (in which only whites and coloroureds could vote) at the hands of a resurgent National Party after the war. This began the road to South Africa's eventual isolation from a world that would no longer tolerate any forms of political discrimination or differentiation based on race only.

General elections and the slow evolution of democracy

From 1910 until the present time, a series of important general elections have been held in a united South Africa. From 1910 until 1948 the franchise to vote was given to whites and to Cape Coloreds (people of mixed race) only. After the ascent of the Nationalist Party in 1948, the Cape Coloreds were taken off the voters' role. Only eligible whites were permited to vote from 1948 until 1994 when the vote was granted to South Africans of every racial group. The 1994 general election was the first post-apartheid vote based on universal suffrage.

There have been three referendums in South Africa: 1960 referendum on becoming a republic; 1983 referendum on implementing the tricameral parliament; and 1992 referendum on becoming a multiracial democracy all of which were held during the era of Nationalist Party control.