Factors affecting the demand for the commodity

There are various factors that affect the demand for commodities some of which arc major (the first four) and others are minor.

Market price of a commodity (Px).

When a consumer goes to the market commodity, she first observes the price of the commodity. The amount of the commodity that the consumer buys depends very much on the price of the commodity itself.

Generally speaking, a fall in price will cause an increase in the amount of the commodity demanded, and a rise in the price will cause a fall in the amount of the commodity demanded. This factor illustrates the demand law:

Income (Y).

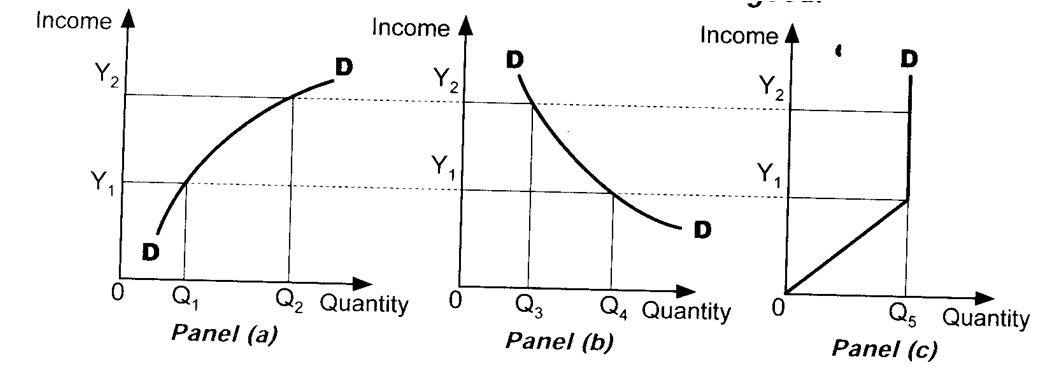

As incomes change, the pattern of demand changes at a certain existing price. Generally, demand increases when incomes increase and vice versa. If income increases and more of the commodity is demanded, such a commodity is referred to as a normal good - it has a positive income elasticity of demand (Figure 2.7, panel (a).

However, there are a few items such as starchy foods (cassava) that tend to experience a decrease in demand as incomes increase. With more income to spend, tastes tend to shift to more expensive goods. As income increases, one may give up cassava and switch to rice. In this case, cassava is an "inferior" good (Figure 2.7, panel (b). The good has a negative income elasticity of demand. The term "inferior" is a relative term. While cassava may be inferior to individual A, it may not be so for individual B.

Another exception is where an increase in income does affect the quantity demanded. A good example of such a commodity is salt. It does not mean that if one's income doubles, one must also double the

amount of salt consumed. The amount of salt consumed remains constant. Practically, this applies to all commodities. There comes a

time, when one has got to stop demanding a certain commodity. For

instance, if one's income doubles, it does not imply that one has to

double the number of tablespoons or dining tables. There is a limit to

everything - the demand does not continue infinitely even though

income increases. Such commodities have a zero income elasticity of

demand (Figure 2.7 panel (c)).

amount of salt consumed. The amount of salt consumed remains constant. Practically, this applies to all commodities. There comes a

time, when one has got to stop demanding a certain commodity. For

instance, if one's income doubles, it does not imply that one has to

double the number of tablespoons or dining tables. There is a limit to

everything - the demand does not continue infinitely even though

income increases. Such commodities have a zero income elasticity of

demand (Figure 2.7 panel (c)).

Figure 2.7 A normal good, inferior good, and an essential good.

Taste (T).

Consumers' taste and preferences play an important role in determining the demand for a product. Taste and preferences depend,

generally, on the social customs, religious values attached to a commodity, habits of the people, the general life-style of the society, and also the age and sex of the consumers. Changes in these factors change the consumers' taste and preferences. As a result, consumers reduce or give up the consumption of some goods and include some others in their consumption basket. When changes take place in tastes and preferences, demand also changes. Favourable tastes increase demand and vice versa. Price of other goods. The demand for a particular good will depend partly on prices of other goods. Two cases can be considered:

generally, on the social customs, religious values attached to a commodity, habits of the people, the general life-style of the society, and also the age and sex of the consumers. Changes in these factors change the consumers' taste and preferences. As a result, consumers reduce or give up the consumption of some goods and include some others in their consumption basket. When changes take place in tastes and preferences, demand also changes. Favourable tastes increase demand and vice versa. Price of other goods. The demand for a particular good will depend partly on prices of other goods. Two cases can be considered:

Price of Substitutes (Ps).

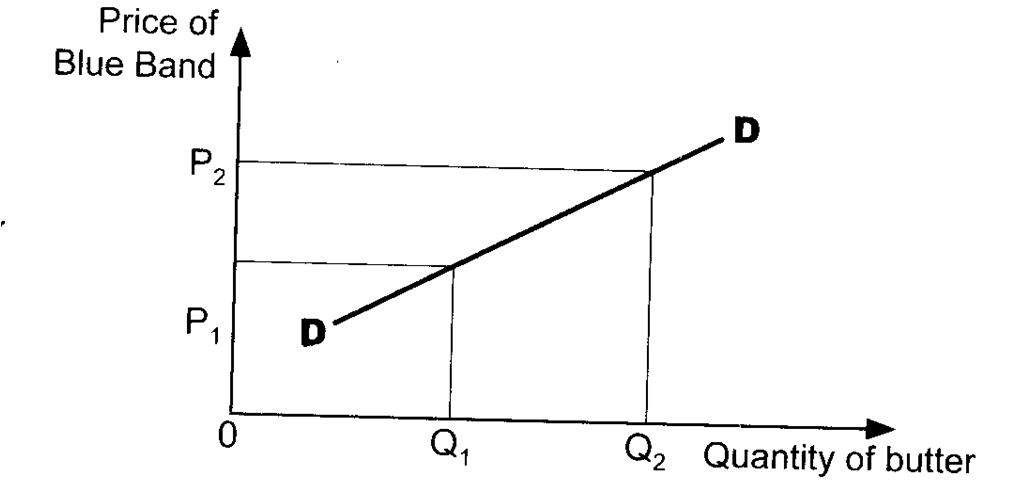

Commodities are said to be substitutes if the demand for the commodity in question varies directly with the price of its substitute (Figure 2.8]. If the demand for the commodity in question increases, the price of its substitute must have increased. The demand for the commodity in question and the price of its substitute move in the same direction. For instance, butter and blue band (margarine) are substitutes. If the demand for butter increases, then the price for blue band must have increased. This is because if the price of blue band increases, (demand for blue band decreases), consumers will switch to butter, thereby increasing the demand for butter.

Price of a substitute (Blue Band) and the quantity demanded in question (butter).

Other examples of substitutes (goods which more or less serve the same purpose and must be within the same price range) are Lux and

Palmolive soap; coffee and tea; Kimbo and Cowboy, Toyota Carina and Toyota Sprinter; a BMW and Audi cars. Hot Loaf and Tip Top bread, etc.

Price of Complements (PC).

Commodities are said to be complements if the demand for the commodity in question varies inversely with the price of its complement (Figure 2.9]. If the demand for the commodity in question (film) increases, the price for its complement (camera) must have decreased, and if the demand for the commodity in question decreases, the price for its complement must have increased.

The demand for the commodity in question and the price of its complement move in opposite direction. If the demand for the film increases, the price for the camera must have decreased and, if the demand for the film decreases, the price for the camera must have increased.

Other examples of complementary goods (goods which are demanded

jointly) are: car and petrol; pen and ink; needle and thread; gun and

bullet, charcoal and charcoal stove, etc. Some examples of complementary goods that are mentioned by some students are not correct: car and tyres - a car is complete only when it has tyres.

jointly) are: car and petrol; pen and ink; needle and thread; gun and

bullet, charcoal and charcoal stove, etc. Some examples of complementary goods that are mentioned by some students are not correct: car and tyres - a car is complete only when it has tyres.

Price of complementary good (camera) and the quantity demanded in

question (films).

question (films).

Advertising. Three cases can be considered.

Advertising expenses on the commodity in question (Ax). This changes the amount of the commodity in question. Generally, an increase in advertising expenses on the commodity in question increases the amount of the commodity demanded and vice versa.

Advertising expenses on a substitute (As). This reduces the demand for the commodity in question. If advertising expenses increase on Blue Band, the demand for butter is likely to reduce.

Advertising expenses on a complementary good (Ac). This increases the demand for the commodity in question. If advertising expenses increase on camera, the demand for films is likely to increase.

Size of population (P). The demand for the product is influenced by the size of population. A big size of population will lead to a more effective demand than a small one provided the population has an ample purchasing power. If the additional population is not employed, then demand will not increase. This implies that, a big size of population does not always imply an increase in demand. Demand will increase only when the population has ample purchasing power.

Income distribution (yd). The distribution pattern of national income also affects the demand for commodity. Generally, inequality of incomes between different groups of people leads to less demand. A more equal, distribution of income leads to more demand.

Government policy (Gp). The demand for some goods is affected by

government policy. Taxation reduces demand while subsidization

increases the demand.

Future prices - expected future prices (Pf).

If future prices are expected to fall, the demand for the commodity will tend to fall, and if future prices are expected to increase, the demand for the commodity will tend to increase.

Seasonal Factors (Sf). Certain commodities are demanded in a

particular period. For example, Christmas cards are demanded just

before the Christmas day. Success cards are demanded just before the

examinations. In other periods, the demand for these cards is almost

non-existent.

Using a functional notation, we can write the following demand

function: Dx = f (Px< Y' T' ps' pc- Ax< As, Ac, P, Yd, Gp, Pf, Sf)

This states simply that the market demand for commodity X is a

function of all the factors listed in the brackets. Although all the factors are undoubtedly important, the price of a commodity (Px) is in many cases the most important factor influencing an individual's demand for it. In economics, we analyse the relationship between a consumer's demand for X and the price of X by assuming that all the other factors remain unchanged i.e. ceteris paribus assumption.

function: Dx = f (Px< Y' T' ps' pc- Ax< As, Ac, P, Yd, Gp, Pf, Sf)

This states simply that the market demand for commodity X is a

function of all the factors listed in the brackets. Although all the factors are undoubtedly important, the price of a commodity (Px) is in many cases the most important factor influencing an individual's demand for it. In economics, we analyse the relationship between a consumer's demand for X and the price of X by assuming that all the other factors remain unchanged i.e. ceteris paribus assumption.

The relationship between the demand for a commodity (X) and the

factors affecting it can be shown in Table 2.3. A (+) sign indicates a

positive relationship between a demand for a commodity and this

particular variable, while a (-) sign shows a negative relationship

between demand for a commodity and that particular variable.

factors affecting it can be shown in Table 2.3. A (+) sign indicates a

positive relationship between a demand for a commodity and this

particular variable, while a (-) sign shows a negative relationship

between demand for a commodity and that particular variable.