JEREMIAH'S TEACHING ON THE NEW COVENANT

Jeremiah. 31 :31 ff

Jeremiah developed a theme of a new covenant in his

teaching. He looked forward to a time when the Lord would make a new covenant

with people of Israel and Judah.

This came as a message of hope to the people of Judah.

The future seemed brighter after a life of suffering.

The new covenant would be different from the old one

which the Lord had made with their ancestors at the foot of Mount Sinai

following their deliverance from Egypt.

Jeremiah said that the new covenant would have laws

written in the heart of the people as opposed to the old covenant where the

laws were written on the store tablets.

In the new covenant, the Lord would be their God and they

would be his people. This would mark a new relationship between the people and

their God.

In the new covenant, everyone, from the least to the

greatest would know the Lord as their God. Therefore, none of them would have

to teach his fellow citizen to know him.

In this covenant, God would forgive the sins of his

people. He would no longer remember their wrongs.

The prophet said the new covenant would require one's

inner commitment towards God. Therefore, it would not be based on external

signs like the circumcision on the male children as was with the old covenant.

The new covenant would require faith. Both Judah and Israel

would be required to believe and trust in God.

The new covenant would mark a new relationship between

Israel and Judah. They would all be God's own people. This signified the

re-union of Israel and Judah

In this new covenant God have a direct relationship with

each individual. It would not require a mediator as was the case with the old

covenant where Moses mediated between the people and God.

The new covenant would benefit all the people of the

world from the least to the greatest. Therefore, all people would be God's

children.

The responsibility of sins would fall upon each

individual. The Lord would no Ionger punish his people as a community in the

event of sinning.

The new covenant would bring hope and unity among God's

people of Israel and Judah. They would accept each other and live as the chosen

people.

Jeremiah said that the new covenant would last forever.

It would be permanent not like the old one which was broken.

The new covenant would be universal. All the people of

the world would benefit from it unlike the other old covenant which only

benefited the people of Israel.

It would be based on repentance. This would help to bring

about reconciliation between God and each individual.

According to Jeremiah, the new covenant would be made between

God and each person thus making it different from the old one which was made

between God and multitude.

In the new covenant, sacrifice or offerings would no

longer be required in order for G to forgive people's sins.

The new covenant would be based on the great commandment

of love. It would mar' an end to hatred and instability among people.

In this covenant, people would only worship God meaning

that the people would m back to their monotheistic faith.

Revision Questions

1.

Examine the main ideas of the new

covenant in Jeremiah 31 3ff.

2.

Why was it necessary for a new

covenant to be made?

3.

How was Jeremiah's teaching about the

new covenant fulfilled in the New Testament?

· It

was fulfilled in the person of Jesus Christ who came to establish God's kingdom

on earth.

· Jesus

came for the salvation of all mankind.

· His

coming back even reconciled God with the sinful man.

· Jesus

required his followers to have faith in him and his teaching.

· Jesus

called for repentance in order for each and every individual to be right with

God.

· Jesus

said each and every individual would be judged according to his or her deeds.

· Jesus

encouraged every believer to worship only the father in Heaven

· Jesus

opened up a direct relationship between each individual and God

· Jesus'

death on the cross reconciled each man in God as fellow human beings.

· Jesus'

death on the cross established God's permanent kingdom on earth

· Jesus

emphasized love as the greatest commandment of all.

THE RELEVANCE OF

THE BOOK OF JEREMIAH TO MODERN CHRISTIANS

•

Should be ready for God's call

•

Christians should respond to God's

call positively

•

Christians should observe monotheism

•

Christians should listen to religious

leaders

•

Christians should seek protection from

God.

•

Christians should be ready for

judgement and punishment

•

Christians should trust God.

•

Christians should remain optimistic

•

Christians should treat each other

fairly.

•

Christians should repent their sins so

that they can be forgiven

•

Christians should serve God with

commitment

•

Christians should use the church for

the rightful purpose

•

Christians should preserve human life.

•

Christians should endure suffering

from life like Jeremiah himself.

•

Christians should speak the truth

•

Christians should serve without fear

and favour.

•

Christians should preach the good news

of salvation.

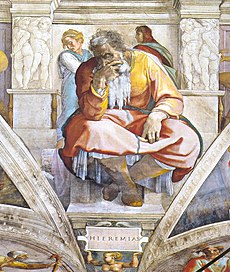

Jeremiah

| Jeremiah | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Anathoth |

| Occupation | Prophet |

| Children | none |

| Parent(s) | Hilkiah |

Jeremiah (/dʒɛrɨˈmaɪ.ə/;[1] Hebrew: יִרְמְיָהוּ,Modern Hebrew: Yirməyāhū, IPA: jirməˈjaːhu,Tiberian: Yirmĭyahu, Greek: Ἰερεμίας, Arabic: إرمياIrmiya) meaning "Yah Exalts", also called the "Weeping prophet",[2] was one of the major prophets of the Hebrew Bible (Christian Old Testament). Jeremiah is traditionally credited with authoring the Book of Jeremiah, 1 Kings, 2 Kingsand the Book of Lamentations,[3] with the assistance and under the editorship of Baruch ben Neriah, his scribe and disciple. Judaism considers the Book of Jeremiah part of its canon, and regards Jeremiah as the second of the major prophets.Christianity also regards Jeremiah as a prophet and he is quoted in the New Testament.[4] It has been interpreted that Jeremiah "spiritualized and individualized religion and insisted upon the primacy of the individual's relationship with God."[5]Islam too considers Jeremiah a prophet, and he is listed as a major prophet in Ibn Kathir's canonical collection of Annals of the Prophets.[6]

About a year after King Josiah of Judah had turned the nation toward repentance from the widespread idolatrous practices of his father and grandfather, Jeremiah's sole purpose was to reveal the sins of the people and explain the reason for the impending disaster (destruction by the Babylonian army and captivity),[7][8] "And when your people say, 'Why has the Lord our God done all these things to us?' you shall say to them, 'As you have forsaken me and served foreign gods in your land, so you shall serve foreigners in a land that is not yours.'"[9] God's personal message to Jeremiah, "Attack you they will, overcome you they can't,"[10] was fulfilled many times in the Biblical narrative: Jeremiah was attacked by his own brothers,[11] beaten and put into the stocks by a priest and false prophet,[12] imprisoned by the king,[13] threatened with death,[14] thrown into a cistern by Judah's officials,[15] and opposed by a false prophet.[16] WhenNebuchadnezzar seized Jerusalem in 586 BC,[17] he ordered that Jeremiah be freed from prison and treated well.[18]

Lineage and early life[edit]

Jeremiah was the son of Hilkiah, a kohen (Jewish priest)[19] from the village of Anathoth.[20][21] Even though he had a joyful early life[22] the difficulties in the books of Jeremiah and Lamentations have prompted scholars to refer to him as "the weeping prophet".[23]Jeremiah was called to prophetic ministry in c. 626 BC.[24] Jeremiah was called by Elohim to give prophesy of Jerusalem's destruction[25] that would occur by invaders from the North.[26] This was because Israel had been unfaithful to the laws of the covenant and had forsaken God by worshiping the Baals.[27] The people of Israel had even gone as far as building high altars to Baal in order to burn their children in fire as offerings.[28]This nation had deviated so far from God that they had broken the covenant, causing God to withdraw his blessings. Jeremiah was guided by God to proclaim that the nation of Israel would be faced with famine, plundered and taken captive by foreigners who would exile them to a foreign land.[29][30]

Chronology[edit]

Jeremiah's ministry was active from the thirteenth year of Josiah, king of Judah (3298 HC,[31] or 626 BC[32]), until after the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of Solomon's Temple in (3358HC, or 587 BC[33]). This period spanned the reigns of five kings of Judah: Josiah, Jehoahaz,Jehoiakim, Jehoiachin, and Zedekiah.[32] The Hebrew-language chronology Seder HaDorothgives Jeremiah's final year of prophecy to be (3350 HC), whereby he transmitted his teachings to Baruch ben Neriah.[34]

King Josiah began a religious reform in Judah at about 622 BC. "Never had there been a reform so sweeping in its aims and so consistent in execution!"[35] Josiah was free to cut off all tribute to Assyria and even extend his power to the north, into the former territory of Israel, because after the death of Ashurbanipal (in 627 BC), the already weakened Assyrian empire began to disintegrate. Also in 627 B.C. Jeremiah received his call to be a prophet and thus with others spurred Josiah's reforms on. "By asserting that the nation was under judgment and would know the wrath of Yahweh if she did not repent, the prophets help to prepare the ground for reform."[36]

After the death of Josiah, Jehoahaz was placed on the throne but the Egyptians took him in exile after only 3 months. The Egyptians made Jehoiakim king; he allowed the swift deterioration of Josiah's reforms and vexed Jeremiah. He wasted the kingdom's resources on a new palace. In 605 BC, the Egyptians were routed by the Babylonians at Carcamesh and thereby the Assyrian Empire vanished. The Babylonians moved into the Philistine plain the next year and devastated Ashkelon as well as causing great anxiety in Jerusalem. Jeremiah took advantage of the situation to preach his "Temple Sermon" (ch. 26). "His preaching was not merely an attack on the state, it was a call to individual men to decide for the Kingdom of God against the kingdom of Jehoiakim. And his own life was an illustration of the immense cost of that decision."[37]

Biblical narrative[edit]

Calling[edit]

The Lord called Jeremiah to prophetic ministry in about 626 BC,[24] about one year after Josiah king of Judah had turned the nation toward repentance from the widespread idolatrous practices of his father and grandfather. Ultimately, Josiah's reforms would not be enough to preserve Judah and Jerusalem from destruction, both because the sins of Manasseh, Josiah's grandfather, had gone too far [38] and as a result of Judah's return to Idolatry (Jer 11.10ff.). Such was the lust of the nation for false gods that after Josiah's death, the nation would quickly return to the gods of the surrounding nations.[39] Jeremiah was appointed to reveal the sins of the people and the coming consequences.[7][8]

In contrast to Isaiah, who eagerly accepted his prophetic call,[40] and similar to Moses who was less than eager,[41] Jeremiah resisted the call by complaining that he was only a child and did not know how to speak.[21] However, the Lord insisted that Jeremiah go and speak as commanded, and he touched Jeremiah's mouth and put the word of the Lord into Jeremiah's mouth.[42] God told Jeremiah to "Get yourself ready!"[43] The character traits and practices Jeremiah was to acquire in order to be ready are specified in Jeremiah 1 and include not being afraid, standing up to speak, speaking as told, and going where sent.[44] Other disciplines that contributed to the training of the young prophet and confirmation of his message are described as not turning to the people,[45] not marrying or fathering children,[46] not going to weddings or funerals,[47] not sitting in a house with feasting,[48] and not sitting in the company of merrymakers.[49] Since Jeremiah emerges well trained and fully literate from his earliest preaching, the relationship between him and the Shaphan family has been used to suggest that he may have trained at the scribal school in Jerusalem over which Shaphan presided.[50][51]

In his early ministry, Jeremiah was primarily a preaching prophet,[52] going where the Lord directed him to preach oracles throughout Israel.[51] He condemned idolatry,[53] the greed of priests, and false prophets.[54] Many years later, God instructed Jeremiah to write down these early oracles and other messages.[55]

Persecution[edit]

Jeremiah's ministry prompted naysayers to plot against him. Even the people of Anathoth sought to kill him. (Jer.11:21-23) Unhappy with Jeremiah's message, possibly for concern that it would shut down the Anathoth sanctuary, his priestly kin and the men of Anathoth conspired to take his life. However, the Lord revealed the conspiracy to Jeremiah, protected his life, and declared disaster for the men of Anathoth.[51][56] When Jeremiah complains to the Lord about this persecution, the Lord explains that the attacks on him will become worse.[57]

Physical persecution started when the priest Pashur ben Immer, a temple official, sought out Jeremiah to have him beaten and put him in the stocks at the Upper Gate of Benjamin for a day. After this, Jeremiah expresses lament over the difficulty that speaking God's word has caused him and regrets becoming a laughingstock and the target of mockery.[58] He recounts how if he tries to shut the word of the Lord inside and not mention God's name, the word becomes like fire in his heart and he is unable to hold it in.[59]

Conflicts with false prophets[edit]

At the same time while Jeremiah was prophesying coming destruction because of the sins of the nation, a number of other prophets were prophesying peace.[60] The Lord had Jeremiah speak against these false prophets.

For example, during the reign of King Zedekiah, The Lord instructed Jeremiah to make a yoke of the message that the nation would be subject to the king of Babylon and that listening to the false prophets would bring a much worse disaster. The prophet Hananiah opposed Jeremiah's message. He took the yoke off of Jeremiah's neck, broke it, and prophesied to the priests and all the people that within two years the Lord would break the yoke of the king of Babylon, but the Lord spoke to Jeremiah saying "Go and speak to Hananiah saying, you have broken the yoke of wood, but you have made instead a yoke of iron." (see: Jeremiah 28:13)

Babylon[edit]

The Biblical narrative portrays Jeremiah as being subject to additional persecutions. After Jeremiah prophesied that Jerusalem would be handed over to the Babylonian army, the king's officials, including Pashur the priest, tried to convince King Zedekiah that Jeremiah should be put to death because he was discouraging the soldiers as well as the people. Zedekiah answered that he would not oppose them. Consequently, the king's officials took Jeremiah and put him down into a cistern, where he sank down into the mud. The intent seemed to be to kill Jeremiah by allowing him to starve to death in a manner designed to allow the officials to claim to be innocent of his blood.[61] A Cushite rescued Jeremiah by pulling him out of the cistern, but Jeremiah remained imprisoned until Jerusalem fell to the Babylonian army in 587 BC.[62]

The Babylonians released Jeremiah, and showed him great kindness, allowing Jeremiah to choose the place of his residence, according to a Babylonian edict. Jeremiah accordingly went to Mizpah in Benjamin with Gedaliah, who had been made governor of Judea.[63]

Egypt[edit]

Johanan succeeded Gedaliah, who had been assassinated by an Israelite prince in the pay of Ammon "for working with the Babylonians." Refusing to listen to Jeremiah's counsel, Johanan fled to Egypt, taking with him Jeremiah and Baruch, Jeremiah's faithful scribe and servant, and the king's daughters.[64] There, the prophet probably spent the remainder of his life, still seeking in vain to turn the people to God from whom they had so long revolted.[64] There is no authentic record of his death.

World views[edit]

Jewish views[edit]

Commentator Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote that the book is written as if Jeremiah not only heard as words but personally felt in his body and emotions the experience of what he prophesied:

- "Are not all my words as fire, sayeth the LORD, and a hammer that shatters rock"

was a clue as to how difficult the overwhelming, personality-shattering experience of being a vehicle for Divine revelation was, on one of the most difficult tasks ever assigned, and how difficult it was to be able to see, in advance, one's own failure.

Rabbinic literature[edit]

In Jewish rabbinic literature, especially the aggadah, Jeremiah and Moses are often mentioned together;[65] their life and works being presented in parallel lines. The following ancient midrashis especially interesting, in connection with Deut. xviii. 18, in which "a prophet like Moses" is promised: "As Moses was a prophet for forty years, so was Jeremiah; as Moses prophesied concerning Judah and Benjamin, so did Jeremiah; as Moses' own tribe [the Levites under Korah] rose up against him, so did Jeremiah's tribe revolt against him; Moses was cast into the water, Jeremiah into a pit; as Moses was saved by a slave (the slave of Pharaoh's daughter); so, Jeremiah was rescued by a slave (Ebed-melech); Moses reprimanded the people in discourses; so did Jeremiah."[66]

Christian views[edit]

Christianity broadly shares the Judaic tradition with respect to its prophets but with an additional focus on elements that might prefigure the coming of Christ. This is where Jeremiah has been of central importance in Christianity insofar as he is a prophet who made an explicit reference to the New Covenant that it incarnates (Jer. 31:31–34). As such it was quoted by Saint Paul in his Letter to the Hebrews, while a theme known as the Lamentations, whose subject is Jeremiah's sorrow at the destruction of Jerusalem, is not only part of the readings in the liturgical year but has given rise to some of the greatest Christian works of art, whether in painting (Rembrand), sculpture (Sluter) or music (Scarlatti).

Islamic views[edit]

As with many other prophets of the Hebrew Bible, Jeremiah is also regarded as a prophet in Islam by many Muslims. Jeremiah is not mentioned in the Qur'an, butMuslim exegesis and literature narrates many instances from the life of Jeremiah and tradition fleshes out his narrative. For example, some hadiths and tafsirs narrate that the Parable of the Hamlet in Ruins is about Jeremiah.[67] Also, in Sura 17(Al-Isra), Ayah 4-7, that is about the two corruptions of children of Israel on the earth, some hadith and tafsir cite that one of these corruptions is the imprisonment and persecution of Jeremiah.[68] According to Ahmadis the memorization of the Qur'an fulfills Jeremiah's prophecy, "I will put my Law within them and I will write it upon their hearts".[69]

Muslim literature narrates a detailed account of thedestruction of Jerusalem, which parallels the account given in the Book of Jeremiah.[70]

Scholarly views[edit]

Scholars cannot prove the authorship of Jeremiah with any certainty, although consensus has gathered around a thesis of multiple sources, mainly because of the contrast between the poetic discourses and the prose narrative. Some modern scholars think the Deuteronomic Schooledited Jeremiah because of the similarity of phrasing between the books of Jeremiah and Deuteronomy. For example, Egypt is referred to as an "iron furnace" in both Jeremiah 11:4 and Deuteronomy 4:20.[71] They also share a similar view of divine justice.[71]

These views of Multiple Sources are however based on a view that anything that is not new information in an ancient text is borrowed from somewhere else. This view refutes that any author could have used other famous works and or worldviews to strengthen or draw similarities to details in their works. While most Liberal Scholars hold this view, few Conservative ones do. Consensus among scholars has not been reached on the multiple source view.[72]

Baha'i views[edit]

'Abdul-Bahá mentions prophecies made by Jeremiah which refer to a man called the Branch as applying to Bahá'u'lláh.[73]

Nebo-Sarsekim tablet[edit]

In July 2007, Assyrologist Michael Jursa translated a cuneiform tablet dated to 595 BC, as describing a Nabusharrussu-ukin as "the chief eunuch" of Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon. Jursa hypothesized that this reference might be to the same individual as the Nebo-Sarsekimmentioned in Jeremiah 39:3.[74][75]

Cultural influence[edit]

Jeremiah inspired the French noun jérémiade, and subsequently the English jeremiad, meaning "a lamentation; mournful complaint,"[76] or further, "a cautionary or angry harangue."[77]

Jeremiah has periodically been a popular first name in the United States, beginning with the early Puritan settlers, who often took the names of Biblical prophets and apostles. In Ireland, Jeremiah was used to "translate" the Irish name Diarmuid.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Wells, John C. (1990). Longman pronunciation dictionary. Harlow, England: Longman. p. 383.ISBN 978-0-582-05383-0.) entry "Jeremiah"

- ^ Jeremiah, New Bible Dictionary, Second Edition, Tyndale Press, Wheaton, IL, USA 1987.

- ^ Lamentations, The Anchor Bible, commentary by Delbert R. Hillers, 1972, pp.XIX-XXIV

- ^ Hebrews 8:8-12 ESV Hebrews 10:16-17 ESV

- ^ The New Bible Dictionary, Second Edition, 1982 p. 563; See also Jeremiah 31

- ^ Qassas Al-Anbiya, Mu'assasa Umm Al-Qura: Mansoura, n.d., page 527

- ^ a b Jeremiah 1-2

- ^ a b Jeremiah and Lamentations: From Sorrow to Hope, Philip Graham Ryken, R. Kent Hughes, 2001, pp.19-36

- ^ Jeremiah 5:19 ESV

- ^ Jeremiah 1:19 The Anchor Bible

- ^ Jeremiah 12:6

- ^ Jeremiah 20:1-4, See also The NIV Study Bible, Zondervan, 1995, p. 1501

- ^ Jeremiah 37:18, Jeremiah 38:28

- ^ Jeremiah 38:4

- ^ Jeremiah 38:6

- ^ Jeremiah 28

- ^ Jeremiah, Lamentations, F.B. Huey, Broadman Press, 1993 pp. 433-439

- ^ Jeremiah 39:11-40:5

- ^ Jeremiah 1:1

- ^ (Jeremiah 1:1)

- ^ a b Jeremiah (Prophet), The Anchor Bible Dictionary Volume 3, Doubleday, 1992 p.686

- ^ Jeremiah 8:18

- ^ "Who Weeps in Jeremiah VIII 23 (IX 1)? Identifying Dramatic Speakers in the Poetry of Jeremiah," Joseph M. Henderson, Vetus Testamentum, Vol. 52, Fasc. 2 (Apr., 2002), pp. 191-206

- ^ a b Jeremiah, Lamentations, Tremper Longman, Hendrickson Publishers, 2008, p. 6

- ^ (Jer.1)

- ^ (Jer.4)

- ^ Jer.2, Jer.3, Jer.5, Jer.9

- ^ (Jeremiah 19:4,5)

- ^ (Jer.10)

- ^ (11)

- ^ Seder HaDoroth year 3298

- ^ a b Jeremiah, New Bible Dictionary, Second Edition, Tyndale Press, 1987 pp. 559-560

- ^ Introduction to Jeremiah, The Jewish Study Bible, Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 917

- ^ Seder HaDoroth, year 3350

- ^ John Bright, A History of Israel, (Westminster John Knox Press: Louisville, KY, 1959) 297

- ^ John Bright, A History of Israel, (Westminster John Knox Press: Louisville, KY, 1959), 298.

- ^ John Bright, The Kingdom of God, (Abingdom Press: Nashville, TN, 1953), 123.

- ^ 2 Kings 23:26-27

- ^ 2 Kings 23:32

- ^ Isaiah 6

- ^ Exodus 4:10-17

- ^ Jeremiah 1:6-9

- ^ Jeremiah 1:17 NIV

- ^ Jeremiah 1

- ^ Jeremiah 15:19

- ^ Jeremiah 16:2

- ^ Jeremiah 16:5

- ^ Jeremiah 16:8

- ^ Jeremiah 15:17

- ^ 2 Kings 22:8-10

- ^ a b c Jeremiah (Prophet), The Anchor Bible Dictionary Volume 3, Doubleday, 1992 p.687

- ^ Jeremiah 1:7

- ^ Jeremiah 3:12-23, Jeremiah 4:1-4

- ^ Jeremiah 6:13-14

- ^ Jeremiah 36:1-10

- ^ Jeremiah 11:18-2:6

- ^ Commentary on Jeremiah, The Jewish Study Bible, Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 950

- ^ Jeremiah 20:7

- ^ Jeremiah 20:9

- ^ Jeremiah 6:13-15, Jeremiah 14:14-16, Jeremiah 23:9-40, Jeremiah 27-28, Lamentations 2:14

- ^ Commentary of Jeremiah, The NIV Study Bible, Zondervan, 1995, p. 1544

- ^ Jeremiah 38

- ^ Jeremiah 40

- ^ a b Jeremiah 43

- ^ This article incorporates text from the 1901–1906 Jewish Encyclopedia, a publication now in thepublic domain.

- ^ Pesiqta, ed. Buber, xiii. 112a

- ^ Tafsir al-Qurtubi, vol 3, p 188; Tafsir al-Qummi, vol 1, p 117.

- ^ Tafsir al-Kashaf, vol 2, p 649; Jawami' al-Jami', vol 2, p 360.

- ^ Arif Humayun. ISLAM THE SUMMIT OF RELIGIOUS EVOLUTION (PDF). Islam International Publications. p. 67. Retrieved June 8, 2014.

- ^ Tabari, i, 646f.

- ^ a b Michael D. Coogan, A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament (New York: Oxford, 2009), 300.

- ^ Gary R. Habermas, The Historical Jesus: Ancient Evidence for the Life of Christ (Joplin, MO: College Press Publishing Company, Inc., 1996),pg. 260

- ^ Bahá'u'lláh and the New Era: An Introduction to the Bahá'í Faith - Page 239, J. E. Esslemont - 2006

- ^ "Ancient Document Confirms Existence Of Biblical Figure". Retrieved 2007-07-16.

- ^ "Jeremiah 39:3 and History: A New Find Clarifies a Mess of a Text - Ancient Hebrew Poetry".typepad.com.

- ^ Webster's encyclopedic unabridged dictionary of the English language. New York: Portland House. 1989. p. 766. ISBN 978-0-517-68781-9.

- ^ "jeremiad - Definition". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster, Inc. 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

References[edit]

- Bright, John. A History of Israel. Westminster John Knox Press: Louisville, KY, 1959.

- Bright, John. The Kingdom of God. Abingdon Press: Nashville, TN, 1953.

- Friedman, Richard E. Who Wrote The Bible?, Harper and Row, NY, USA, 1987.

- Abraham Joshua Heschel, The Prophets. HarperCollins Paperback, 1975. ISBN 978-0-06-131421-6

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). "Jeremiah". Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). "Jeremiah". Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

Further reading[edit]

- Ackroyd, Peter R. (1968). Exile and Restoration: A Study of Hebrew Thought in the Sixth Century BC. Philadelphia: Westminster Press.

- Bright, John (1965). The Anchor Bible: Jeremiah (2nd ed.). New York: Doubleday.

- Meyer, F.B. (1980). Jeremiah, priest and prophet (Revised ed.). Fort Washington, PA: Christian Literature Crusade. ISBN 0-87508-355-2.

- Perdue, Leo G.; Kovacs, Brian W., eds. (1984). A Prophet to the nations : essays in Jeremiah studies. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 0-931464-20-X.

- Rosenberg, Joel (1987). "Jeremiah and Ezekiel". In Alter, Robert; Kermode, Frank. The literary guide to the Bible. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-87530-3.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jeremiah. |

- Jeremiah Jewsih Encyclopedia 1906

"Jeremias (2)". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"Jeremias (2)". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.- Download Lamentations with linear Hebrew and English and afterword, from neohasid.org

- History of ancient Israel and Judah

|

||

|

||

|

|||

|

This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the article "".

Jeremiah, Hebrew Yirmeyahu, Latin Vulgate Jeremias (born probably after 650 bce, Anathoth, Judah—died c.570 bce, Egypt), Hebrew prophet, reformer, and author of a biblical book that bears his name. He was closely involved in the political and religious events of a crucial era in the history of the ancient Near East; his spiritual leadership helped his fellow countrymen survive disasters that included the capture of Jerusalem by the Babyloniansin 586 bce and the exile of many Judaeans to Babylonia.

Life and times

Jeremiah was born and grew up in the village of Anathoth, a few miles northeast of Jerusalem, in a priestly family. In his childhood he must have learned some of the traditions of his people, particularly the prophecies of Hosea, whose influence can be seen in his early messages.

The era in which Jeremiah lived was one of transition for the ancient Near East. The Assyrian empire, which had been dominant for two centuries, declined and fell. Its capital, Nineveh, was captured in 612 by the Babyloniansand Medes. Egypt had a brief period of resurgence under the 26th dynasty (664–525) but did not prove strong enough to establish an empire. The new world power was the Neo-Babylonian empire, ruled by a Chaldean dynasty whose best known king was Nebuchadrezzar. The small and comparatively insignificant state of Judah had been a vassal of Assyria and, when Assyria declined, asserted its independence for a short time. Subsequently Judah vacillated in its allegiance between Babylonia and Egypt and ultimately became a province of the Neo-Babylonian empire.

According to the biblical Book of Jeremiah, he began his prophetic career in 627/626—the 13th year of King Josiah’s reign. It is told there that he responded to Yahweh’s (God’s) call to prophesy by protesting “I do not know how to speak, for I am only a youth,” but he received Yahweh’s assurance that he would put his own words into Jeremiah’s mouth and make him a “prophet to the nations.” A few scholars believe that after his call Jeremiah served as an official prophet in the Temple, but most believe that this is unlikely in view of his sharp criticism of priests, prophets, and the Temple cult.

Jeremiah’s early messages to the people were condemnations of them for their false worship and social injustice, with summons to repentance. He proclaimed the coming of a foe from the north, symbolized by a boiling pot facing from the north in one of his visions, that would cause great destruction. This foe has often been identified with the Scythians, nomads from southern Russia who supposedly descended into western Asia in the 7th century and attacked Palestine. Some scholars have identified the northern foe with the Medes, the Assyrians, or the Chaldeans (Babylonians); others have interpreted his message as vague eschatological predictions, not concerning a specific people.

In 621 King Josiah instituted far-reaching reforms based upon a book discovered in the Temple of Jerusalem in the course of building repairs, which was probably Deuteronomy or some part of it. Josiah’s reforms included the purification of worship from pagan practices, the centralization of all sacrificial rites in the Temple of Jerusalem, and perhaps an effort to establish social justice following principles of earlier prophets (this program constituted what has been called “the Deuteronomic reforms”).

Jeremiah’s attitude toward these reforms is difficult to assess. Clearly, he would have found much in them with which to agree; a passage in chapter 11 of Jeremiah, in which he is called on by Yahweh to urge adherence to the ancient Covenant upon “the men of Judah and the inhabitants of Jerusalem,” is frequently interpreted as indicating that the prophet travelled around Jerusalem and the villages of Judah exhorting the people to follow the reforms. If this was the case, Jeremiah later became disillusioned with the reforms because they dealt too largely with the externals of religion and not with the inner spirit and ethical conduct of the people. He may have relapsed into a period of silence for several years because of the indifferent success of the reforms and the failure of his prophecies concerning the foe from the north to materialize.

Some scholars doubt that Jeremiah’s career actually began as early as 627/626 bce and question the accuracy of the dates in the biblical account. This view arises from the difficulty of identifying the foe from the north, which seems likely to have been the Babylonians of a later time, as well as the difficulty of determining the prophet’s attitude toward the Deuteronomic reforms and of assigning messages of Jeremiah to the reign of Josiah. In the opinion of such scholars, Jeremiah began to prophesy toward the end of the reign of Josiah or at the beginning of the reign of Jehoiakim (609–598).

Early in the reign of Jehoiakim, Jeremiah delivered his famous “Temple sermon,” of which there are two versions, one in Jeremiah, chapter 7, verses 1 to 15, the other in chapter 26, verses 1 to 24. He denounced the people for their dependence on the Temple for security and called on them to effect genuine ethical reform. He predicted that God would destroy the Temple of Jerusalem, as he had earlier destroyed that of Shiloh, if they continued in their present path. Jeremiah was immediately arrested and tried on a capital charge. He was acquitted but may have been forbidden to preach again in the Temple.

The reign of Jehoiakim was an active and difficult period in Jeremiah’s life. That king was very different from his father, the reforming Josiah, whom Jeremiah commended for doing justice and righteousness. Jeremiah denounced Jehoiakim harshly for his selfishness, materialism, and practice of social injustice.

Near the time of the Battle of Carchemish, in 605, when the Babylonians decisively defeated the Egyptians and the remnant of the Assyrians, Jeremiah delivered an oracle against Egypt. Realizing that this battle made a great difference in the world situation, Jeremiah soon dictated to his scribe, Baruch, a scroll containing all of the messages he had delivered to this time. The scroll was read by Baruch in the Temple. Subsequently it was read before King Jehoiakim, who cut it into pieces and burned it. Jeremiah went into hiding and dictated another scroll, with additions.

When Jehoiakim withheld tribute from the Babylonians (about 601), Jeremiah began to warn the Judaeans that they would be destroyed at the hands of those who had previously been their friends. When the King persisted in resisting Babylonia, Nebuchadrezzar sent an army to besiege Jerusalem. King Jehoiakim died before the siege began and was succeeded by his son, Jehoiachin, who surrendered the capital to the Babylonians on March 16, 597, and was taken to Babylonia with many of his subjects.

The Babylonians placed on the throne of Judah a king favourable to them, Zedekiah (597–586 bce), who was more inclined to follow Jeremiah’s counsel than Jehoiakim had been but was weak and vacillating and whose court was torn by conflict between pro-Babylonian and pro-Egyptian parties. After paying Babylonia tribute for nearly 10 years, the King made an alliance with Egypt. A second time Nebuchadrezzar sent an army to Jerusalem, which he captured in August 586.

Early in Zedekiah’s reign, Jeremiah wrote a letter to the exiles in Babylonia, advising them not to expect to return immediately to their homeland, as false prophets were encouraging them to believe, but to settle peaceably in their place of exile and seek the welfare of their captors. When emissaries from surrounding states came to Judah in 594 to enlist Judah’s support in rebellion against Babylonia, Jeremiah put a yoke upon his neck and went around proclaiming that Judah and the surrounding states should submit to the yoke of Babylonia, for it was Yahweh who had given them into the hand of the King of Babylonia. Even to the time of the fall of Jerusalem, Jeremiah’s message remained the same: submit to the yoke of Babylonia.

When the siege of Jerusalem was temporarily lifted at the approach of an Egyptian force, Jeremiah started to leave Jerusalem to go to the land of the tribe of Benjamin. He was arrested on a charge of desertion and placed in prison. Subsequently he was placed in an abandoned cistern, where he would have died had it not been for the prompt action of an Ethiopian eunuch, Ebed-melech, who rescued the prophet with the King’s permission and put him in a less confining place. King Zedekiah summoned him from prison twice for secret interviews, and both times Jeremiah advised him to surrender to Babylonia.

When Jerusalem finally fell, Jeremiah was released from prison by the Babylonians and offered safe conduct to Babylonia, but he preferred to remain with his own people. So he was entrusted to Gedaliah, a Judaean from a prominent family whom the Babylonians appointed as governor of the province of Judah. The prophet continued to oppose those who wanted to rebel against Babylonia and promised the people a bright and joyful future.

After Gedaliah was assassinated, Jeremiah was taken against his will to Egypt by some of the Jews who feared reprisal from the Babylonians. Even in Egypt he continued to rebuke his fellow exiles. Jeremiah probably died about 570 bce. According to a tradition that is preserved in extrabiblical sources, he was stoned to death by his exasperated fellow countrymen in Egypt.

Prophetic vocation and message

This sketch of Jeremiah’s life portrays him as a courageous and persistent prophet who often had to endure physical suffering for his fidelity to the prophetic call. He also suffered inner doubts and conflicts, as his own words reveal, especially those passages that are usually called his “confessions” (Jer. 11:18–12:6; 15:10–21; 17:9–10, 14–18; 18:18–23; 20:7–12, 14–18). They reveal a strong conflict between Jeremiah’s natural inclinations and his deep sense of vocation to deliver Yahweh’s message to the people. Jeremiah was by nature sensitive, introspective, and perhaps shy. He was denied participation in the ordinary joys and sorrows of his fellowmen and did not marry. He thus could say, “I sat alone,” with God’s hand upon him. Jeremiah had periods of despondency when he expressed the wish that he had never been born or that he might run away and live alone in the desert. He reached the point of calling God “a deceitful brook, . . . waters that fail” and even accused God of deceiving and overpowering him. Yet there were times of exaltation when he could say to God: “Thy words became to me a joy and the delight of my heart”; and he could speak of Yahweh as “a dread warrior” fighting by his side.

As a prophet Jeremiah pronounced God’s judgment upon the people of his time for their wickedness. He was concerned especially with false and insincere worship and failure to trust Yahweh in national affairs. He denounced social injustices but not so much as some previous prophets, such as Amos and Micah. He found the source of sin to be in the weakness and corruption of the hearts of men—in what he often called “the stubbornness of the evil heart.” He considered sin to be unnatural; he emphasized that some foreign nations were more loyal to their pagan (false) deities than Judah was to Yahweh (the real God), and he often contrasted nature’s obedience to law with man’s disobedience to God.

Jeremiah had more to say about repentance than any other prophet. He called upon men to turn away from their wicked ways and dependence upon idols and false gods and return to their early covenantal loyalty to Yahweh. Repentance thus had a strong ethical colouring, since it meant living in obedience to Yahweh’s will for the individual and the nation.

In the latter part of his career Jeremiah had to struggle against the despair of his people and give them hope for the future. He expressed his own hope vividly by an action that he undertook when the Babylonians were besieging Jerusalem and he was in prison. He bought, from a cousin, a field in Anathoth, his native town. In the presence of witnesses he weighed out the money and made the contracts and said, “Thus says the Lord of hosts, the God of Israel: Houses and fields and vineyards shall again be bought in this land.” In this and other ways he expressed his hope for a bright future for Israel in its own land.

Jeremiah’s most important prophecy concerning the future is one regarding the New Covenant (Jer. 31:31–34). While the present literary form of the passage is probably not Jeremiah’s, the thought is essentially his. He prophesied of a time when Yahweh would make a covenant with Israel, superseding the old Mosaic Covenant; Yahweh would write his law upon the hearts of men (rather than on tables of stone), and all would know God directly and receive his forgiveness. This New Covenant prophecy was very influential inNew Testament times. It is quoted in the Letter to the Hebrews and lies behind words attributed to Jesus at the Last Supper: “This cup is the new covenant in my blood.”