Introduction

The political history of Nigeria from 1945 to I960 was less a struggle for independence than a struggle for supremacy within a federal state between the three most populous ethnic communities: the Hausa-Fulani of the North, the Yoruba of the West, and the Ibo of the East. Each of these three communities expressed its political sub-nationalism (regional nationalism as distinct from a nationwide nationalism) in a regionally based political party.

The Hausa-Fulani overwhelmingly supported the Northern People's Congress (NPC), led by the Sardauna of Sokoto, Sir Ahmadu Bello, and his lieutenant Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, a man from the common people. The Yoruba rallied behind the Action Group, led by Chief Obafemi Awolowo. The Ibo rallied to the National Council of Nigeria and Cameroons (NCNC).

From 1944 until 1951, when the AG was founded, the NCNC had aspired to become a national not a regional party and to unite Ibo and Yoruba. However, the opposition of many Yoruba to the leadership of Nnamdi Azikiwe (Ibo) added to the competition between Yoruba and Ibo Western-educated elites to secure positions in the civil service, commercial firms, churches and institutions of learning, led to the break-up of the NCNC and the emergence of the AG as a party for Yoruba interests. The Ibo remained in the NCNC and increasingly transformed it into a party to serve Ibo interests.

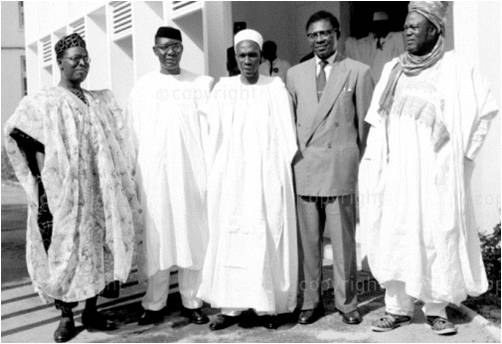

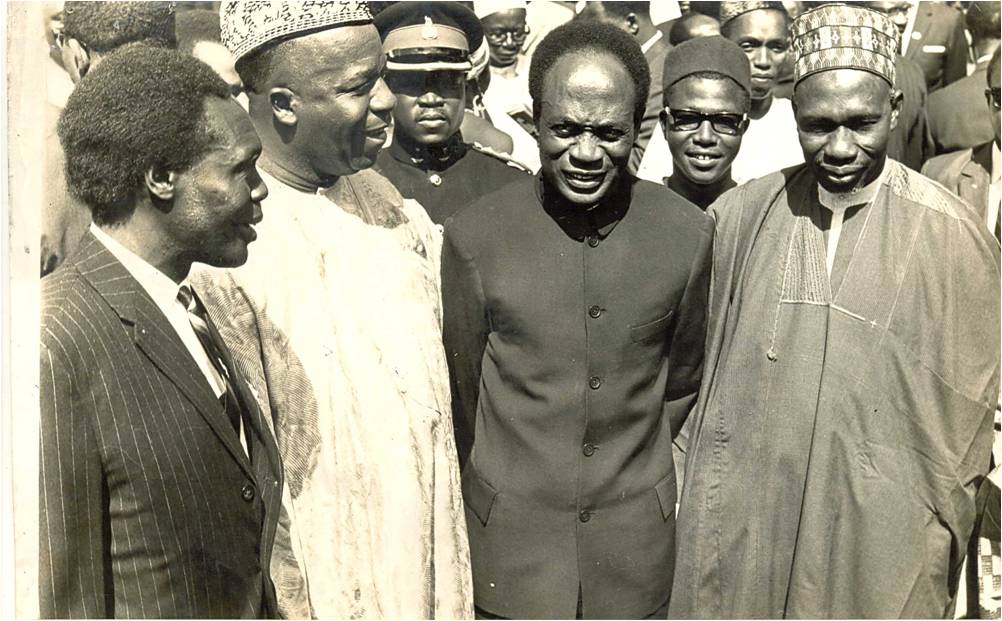

|

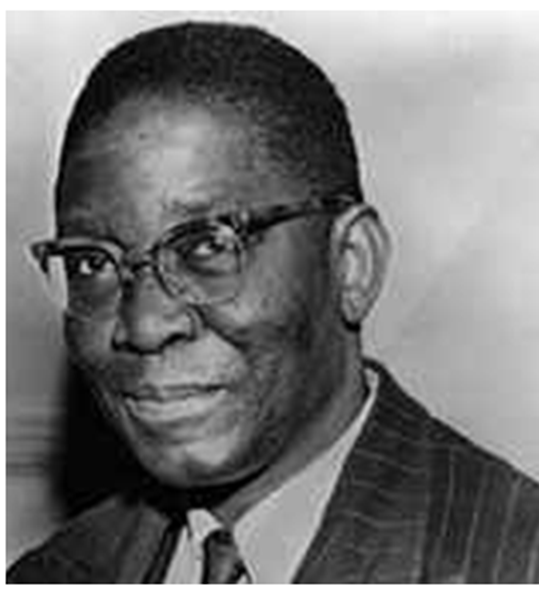

Nnamdi Azikiwe was an important nationalist figure in colonial Nigeria and became the first president of independent Nigeria in 1960. |

The problem of evolving a strong one-Nigeria national consciousness has been succinctly summed up by Tekena Tamuno, Nigeria's foremost constitutional historian. Tamuno has observed: 'Historically, it was easier to establish the Nigerian state than to nourish the Nigerian nation. Though the former was to a large extent achieved through the 1914 Amalgamation, the latter eluded both British officials and Nigerians for several decades thereafter.'5

In the same article Tamuno refers to a number of factors which have fostered disunity in the country: heterogeneous ethnic composition, cultural diversity, vast size, communications difficulties, varied administrative practices, political and constitutional arrangements and the introduction of federalism, personality clashes between Nigerian leaders before and after independence, and the lack of a strong unifying ideology.

Tamuno makes it clear that none of the above factors, by themselves, 'would have constituted an impregnable obstacle to the evolution of a strong national consciousness', but that in combination they paved the way for serious disunity. The two factors he emphasizes as the causes of the sectionalism of the 1950s are cultural diversity (southern Christians against northern Muslims) and varying Tares of educational advance with the north feeling keenly its educational disadvantage.

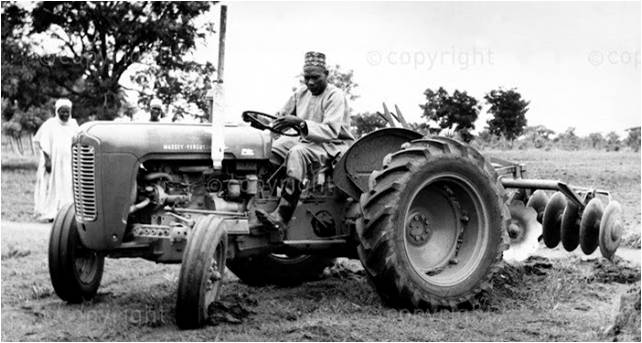

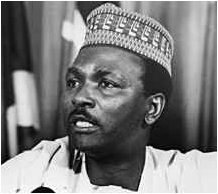

Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa (launching agriculture project) served as prime minister of Nigeria from 1960, when Nigeria gained independence from British rule, to 1966, when Balewa was killed in a military coup.

The event that precipitated the emergence of three regionally based political parties and the development of ethnic sub-nationalist politics in Nigeria was the issuing of the Macpherson Constitution of 1951. Governor Macpherson had allowed public opinion to express itself in the formation of the new constitution in a series of village, divisional and provincial meetings followed by a national conference at Ibadan in 1950.

The constitution embodied many of the recommendations of the Ibadan conference. Thus Nigerians as well as British decided on a federal system of three regions which favoured the three major ethnic communities. Regional assemblies were to be elected, though indirectly, by electoral colleges, and regional governments would be appointed to control regional revenues. The central House of Representatives was elected by the regional assemblies.

On the basis of population the North was given 68 seats and the East and West 34 each. The Council of Ministers was to be composed of four members from each region plus six British officials. The Constitution was a compromise aiming to accommodate the hopes of the southern modernists and the fears of the northern traditionalists. As such it proved to be contradictory and unworkable. It applied the elective principle throughout the country and gave considerable powers to the central government, but ensured that the House of Representatives was regionally controlled so as to avoid its capture by a united mass nationalist movement as in the Gold Coast. Moreover, the composition of the Council of Ministers prevented any nationalist majority in the central executive.

The Macpherson Constitution encouraged the rise of ethnic political parties. John Hatch has written:

It was partly the effect of this constitution which diverted the attention of the politically conscious to regional rather than national efforts. Azikiwe and Obafemi Awolowo had both favoured some form of federation to circumvent the deeply-rooted conservatism of the north. Now they recognised the danger of the Macpherson constitution giving the north full powers to determine national policy if it could find a few allies in the south. Both reacted in the same way, by concentrating their efforts on securing greater powers for their regions and organising their parties on a mainly regional basis.6

Similarly, the NPC concentrated after 1951 on consolidating its support in the northern region. Ahmadu Bello, the party leader, became the head of the northern regional government and assigned to Balewa the lesser task of leading the NPC in Lagos. The NPC's slogan became 'One North, one people', not 'One Nigeria, one people'.

The Macpherson Constitution had to be replaced within three years. In the meantime it proved incapable of handling a serious political crisis which almost broke up Nigeria. In 1953 Antony Enahoro, an Action Group backbencher, introduced a motion in the federal parliament demanding self-government for Nigeria in 1956. Opposition from the NPC and from a majority in the Council of Ministers led to the resignation of the AG ministers and to the AG and NCNC members walking out of the House. Tension rose rapidly as southern crowds insulted Balewa and other northern members on the steps of the House. and when Awolowo toured the North in a campaign to detach the northern masses from their leaders.

Awolowo's

visit to Kano city in May 1953 resulted in pitched battles between northerners

and southerners and 36 people were killed. Following the Kano fighting, the

northern House of Assembly and northern House of Chiefs in an emergency joint

session endorsed an eight-point federal programme, demanding that the central

government's powers be restricted to defence, foreign affairs, and customs

duties. This was virtual secession by the North, The Colonial Secretary chaired

a constitutional conference in London in July and August in 1953 which revised

the 1951 constitution, by giving more powers to the regions. Marketing boards,

mining and income taxes, tobacco duties and excise, the civil service and the

judiciary were all regionalized. The NCNC and AG accepted this weakening of the

central government (formalized in the new constitution of 1954) in order to

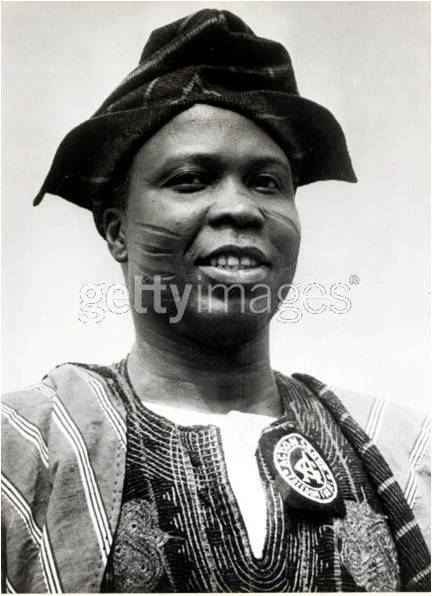

keep the North in the Federation. A weak Nigeria was better than no Nigeria. Chief Awolowo

Awolowo's

visit to Kano city in May 1953 resulted in pitched battles between northerners

and southerners and 36 people were killed. Following the Kano fighting, the

northern House of Assembly and northern House of Chiefs in an emergency joint

session endorsed an eight-point federal programme, demanding that the central

government's powers be restricted to defence, foreign affairs, and customs

duties. This was virtual secession by the North, The Colonial Secretary chaired

a constitutional conference in London in July and August in 1953 which revised

the 1951 constitution, by giving more powers to the regions. Marketing boards,

mining and income taxes, tobacco duties and excise, the civil service and the

judiciary were all regionalized. The NCNC and AG accepted this weakening of the

central government (formalized in the new constitution of 1954) in order to

keep the North in the Federation. A weak Nigeria was better than no Nigeria. Chief Awolowo

In the elections of 1954 (as in those of 1951-2) the NPC won the North, the NCNC the East and the AG the West, The NPC and the NCNC formed a coalition government at the federal level, rather than the NCNC and the AG. This unlikely alliance was virtually imposed by the constitution. The coalition was required in order to make the Council of Ministers function. The NCNC won more federal seats in the West than the AG (though less regional seats than the AG).

This gave the NCNC six ministerial seats, three for the East and three for the West. The NPC gained the three for the North. Thus the NCNC and the NPC found themselves in the federal cabinet and obliged to work together. It was an alliance of expediency, not conviction.

A weakened central government enabled progress towards independence to be made, as the North no longer feared independence under a strong central government led by a radical southerner. In March 1957 the federal House carried a unanimous demand for independence in 1959. After a conference, Britain finally agreed on independence in October I960.

In August 1957 a federal Prime Minister was appointed. Balewa was the obvious choice as a northerner who believed in co-operation with the South. Unfortunately Balewa's elevation did not give him even equal authority with Bello in the North, a factor which played a major part in the tragic events of 1966.

For the 1959 election the Federal House was expanded to 720 seats: 174 in the North, 73 in the East, 62 in the West, 8 in Southern Cameroons and 3 in Lagos. Awolowo's AG hoped to defeat the NPC-NCNC (Hausa-Ibo) coalition by appealing to the minority ethnic communities throughout the country. By themselves the minorities constituted almost half of the country's population. The AG thus acquired a more national image than the other two major parties. In the election the AG won 73 seats, 25 in the North and 14 in the East. However, the NCNC won 89 and the NPC 142. The Northern Elements Progressive Union (NEPU), the northern commoners' party led by Aminu Kano, won eight seats. The Three Nigerias theory had triumphed again and the NPC-NCNC coalition held together.

General Yakubu Gowon headed the federal military government of Nigeria from 1966 to 1975, when he was overthrown in a bloodless coup led by Brigadier Murtala Ramat Muhammad. The photograph shows Gowon in 1973

Nigeria became independent on 1 October I960, with Nnamdi Azikiwe, an easterner, as Governor-General (President of the Republic in 1963), Tafawa Balewa, a northerner, as federal Prime Minister, and Obafemi Awolowo, a westerner, as leader of the opposition.

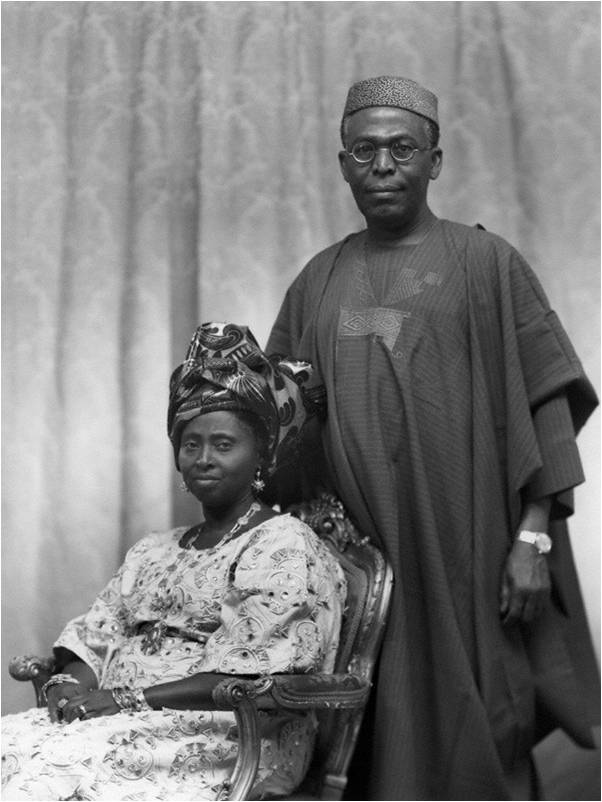

Chief Akintola

Chief Akintola

The 1959 federal election aroused Hausa and Ibo ethnic fears when the AG invaded their regions and campaigned among their minorities. In the years after independence the NPC-NCNC coalition took revenge on the AG by creating a Mid-West state out of the NCNC-dominated eastern part of the West around Benin. A split developed among the Yoruba in the AG, between Awolowo's 'one Nigeria' group and Chief Samuel Akintola's supporters who wished to abandon the minorities and join the federal coalition. Akintola's section was considerably assisted by Awolowo's detention in 1962 and the open rigging of the 1964 federal election and the 1965 western regional election which brought ethnic sub-nationalist tension to boiling point.

The emergence of Akintola as a Yoruba leader enabled the Hausa-Fulani in the NPC to prepare to abandon the hated coalition with the Ibo-dominated NCNC in favour of an alliance with Akintola. This ethnic realignment was forestalled at Cabinet level by the first Nigerian military coup of January 1966.

National Movements and New States in Africa