Introduction

The

Zanzibar uprising was a revolution, primarily arising out of popular

discontent and the challenge of armed civilians, rather than from any

professional army. The Zanzibar experience cannot therefore be

described as a military coup.

In retrospect the Revolution on the 'Isle of Cloves' seems an almost

inevitable result of racial pluralism on Zanzibar and Pemba and the

tendency for racial divisions to coincide with economic and political

inequalities. An Arab minority of about 50 000 dominated an African

majority of about 250 000. The Arabs owned the vast bulk of arable land

whereas the Africans were peasants and labourers. The indigenous and

diverse 'Shirazi' African communities (called 'Shirazi' because they

were part descended from the early Zanzibar Arabs who came from Shiraz)

were largely peasants and fishermen, whereas the 'mainland Africans'

were farm-squatters, urban labourers or house-servants.

A key element in the socio-economic pattern was the economic dominance

of the 20 000 Asians of Indo-Pakistani origin who controlled commerce,

finance and the intermediate grades of the civil service. The Arabs

were politically dominant too, controlling the legislature, the

administration and the police; a process the British had encouraged,

interpreting the protectorate as an obligation to protect the interests

of the Arab community. Africans were discriminated against in

employment - in appointments to the civil service and the police and to

Asian business firms, except in menial tasks. Unequal job opportunity

was related to educational imbalance, whereby the distribution of

education was related to ability or inability to pay fees.

In Zanzibar city, Stone Town reflects the Arab past of the island of

Zanzibar. Stone Town is the oldest section of the city, built in the

18th century for the island's growing population of Omani Arab traders.

When the mainland states of East Africa began to make constitutional

progress, the Sultan and his British advisers made plans to transform

the sultanate into a constitutional monarchy under Arab elective

leadership, not into an African state. Nevertheless, the educated Arab

elite as a whole was more far sighted and saw a vision of an

Arab-African partnership. From 1954 to 1956 the Arab Association

campaigned for a common roll; its members did not fear swamping by

Africans because they believed they could lead and control them - after

all, the Africans were divided into diverse communities.

In the 1957 Problems of disunity: conflicts and uprisings election for

a limited number of seats the newly formed Arab-led Zanzibar

Nationalist Party (ZNP) of civil servants and landowners campaigned for

African support. The African and Shirazi Associations decided to

contest as rival organizations. The Hadimu Shirazi of Zanzibar Island,

who had lost their best land to the Arabs, shared the anti-Arab

sentiments of the mainland Africans; the Shirazi of Pemba, however,

felt closer to the Arabs than to the mainland Africans. The results

reflected the communal divisions on the two islands, with several

parties gaining seats but the ZNP winning more because of split votes

among the African and Shirazi parties.

The Afro-Shirazi Party (ASP), led by Abeid Karume reacted to the 1957

election results by organizing a boycott of Arab shops. In retaliation

Arab land owners evicted African squatters and refused to employ

African workers unless they joined the ZNP, In the January 1961

election the Pemba Shirazis under Muhammad Shamte, shocked by the ASP's

anti-Arab stance, split from it. Out of 23 seats the ASP won (en, the

ZNP nine and Shamte's People's Party three. The PP then split, to give

the ASP and the ZNP eleven seats each, so another election was held in

June.

This time the ASP and the ZNP won ten each and the PP won three. A

ZNP-PP coalition was formed, with Shamte as Prime Minister. The

coalition was a bitter disappointment for the ASP and in a week of

African rioting in Zanzibar city and on the plantations about a hundred

Arabs were killed- The pre-independence election of July 1963 produced

another victory for the ZNP-PP coalition which won 18 seats out of 31.

The ASP had gained 54 per cent of the votes cast, but these votes were

densely concentrated in certain constituencies, which counted for

little in a first-past-the-post election system. Therefore, between

1957 and 1963 four elections were held on a non-racial franchise, but

an Arab-led party was able to win them by attracting sufficient African

support. At independence in December 1963 the Arabs continued to

control the political life of Zanzibar. To many Africans it seemed that

if they could not overthrow Arab rule in a constitutional manner, they

would have to do so by violent means.

The emergence of Umma, a new radical party led by the socialist Abdul

Rahman Muhammad (Babu), which broke away from the ruling ZNP on the eve

of independence, severely weakened it. Could the ASP bide its time and

unite with Umma to defeat the ZNP in a future election? Many ASP

leaders and supporters dismissed this possibility because the ZNP-PP

government seemed determined not to let the constitutional process

work. Laws were made to prevent opposition leaders going abroad. No

attempt was made at social reform; rather the opposite, as British

funds for agricultural development were paid out to the large (Arab)

landowners for crop diversification schemes rather than to the

peasantry. There was no plan for land reform. The insecurity felt by

the government was shown when African policemen were discharged for

suspected disloyalty.

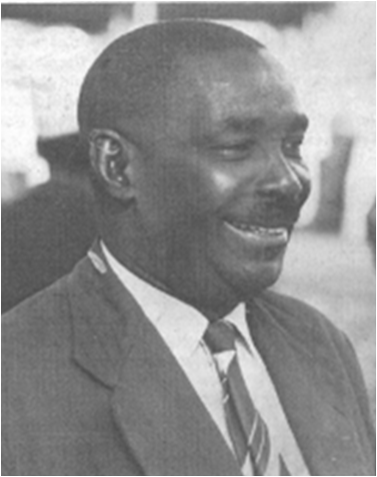

ABEID KARUME became vice President after the revolution.

Several discharged policemen fought in John Okello's revolutionary army

which seized power in a revolution on the night of 11-12 January.

Okello was a Langi from Lango in northern Uganda, who had come to

Zanzibar in 1952 at the age of 21. He had worked as a painter,

stone-cutter and casual labourer before becoming a minor branch

official of the ASP on Pemba Island. In 1963 he moved to Zanzibar

Island. Okello succeeded in carrying out his revolution because of a

number of factors. One was the secrecy of his planning, among a few

militants (not the ASP leaders) in the villages.

The government was aware of the ASP leadership's vague plans for revolt

at a later date; it was taken by surprise by Okello's revolt of the

rank-and-file. The ASP leaders were as surprised as the government when

the revolution took place. Another factor was that on the evening of 11

January a special Ramadan festival was being held in Zanzibar city; the

revolutionaries used it as a cover to enter the town individually and

then assemble at a prearranged place in the African quarter. A third

factor was the seizure of Ziwani armoury, after which the

revolutionaries were able to capture the police station at Mtoni.

After Okello's 'army' seized Zanzibar city ASP supporters went on the

rampage, looting and destroying Arab and Asian shops and businesses,

killing thousands of Arabs and forcing thousands more to flee from the

islands. Okello set up a Revolutionary Council made up of himself and

ASP and Umma leaders. Sultan Jamshid and his ministers escaped in the

royal yacht and flew from Dar-es-Salaam to exile in Britain.

Control over weapons was the most critical factor in Okello's

revolution. By Okello's account, his army did not come into possession

of a single modern weapon until the attack on the government was

initiated, and the group skillfully approached the principal armoury at

Ziwani. Okello claims that until he personally seized a rifle from the

sentry guarding the armoury, his followers were being equipped with

only bows and arrows, spears, and pangas. The arms thus obtained made

all the difference to the success of the confrontation with the age-old

sultanate.

The strategy for the tilting of the balance depended on surprise. When

the little group had overcome the guards at the armoury, in a swift

surprise move they proceeded to distribute arms and ammunition among

the revolutionaries. Thus, when dawn broke on Sunday morning, 12

January 1964, and reporters on the scene caught their first glimpse of

the revolutionaries, they saw a fairly well-equipped soldiery.

John Okello was a trans- national figure in the sense that he was a

Ugandan who had led a revolution in Zanzibar, He was someone drawn from

another society but cast in the role of initiator of fundamental change

in a country of later adoption. Why was a Ugandan successful in

launching a revolution outside his own country? In terms of roots on

the island, Okello was more of a foreigner in Zanzibar than the Sultan

he overthrew. The Sultan was born a Zanzibar!; so was his father, his

grandfather and his grandfather's father. But in terms of ethnic

identity it was the Sultan who was the marginal man, part- Arab,

part-African, more fully Zanzibari than the man who overthrew him but

less purely African than his enemies.

John Okello was a trans- national figure in the sense that he was a

Ugandan who had led a revolution in Zanzibar, He was someone drawn from

another society but cast in the role of initiator of fundamental change

in a country of later adoption. Why was a Ugandan successful in

launching a revolution outside his own country? In terms of roots on

the island, Okello was more of a foreigner in Zanzibar than the Sultan

he overthrew. The Sultan was born a Zanzibar!; so was his father, his

grandfather and his grandfather's father. But in terms of ethnic

identity it was the Sultan who was the marginal man, part- Arab,

part-African, more fully Zanzibari than the man who overthrew him but

less purely African than his enemies.

For a delirious few weeks John Okello might indeed have derived his

mystique from his distance. The local Africans in Zanzibar had

inter-penetrated with the 'Arabs, culturally, religiously and

biologically. Islam was the religion of the great majority of Africans,

as well as of the Arabs. Kiswahili was the language of both groups, and

Swahili as a culture, born of both Arab and African traditions, was

dominant in the population as a whole.

For a delirious few weeks John Okello might indeed have derived his

mystique from his distance. The local Africans in Zanzibar had

inter-penetrated with the 'Arabs, culturally, religiously and

biologically. Islam was the religion of the great majority of Africans,

as well as of the Arabs. Kiswahili was the language of both groups, and

Swahili as a culture, born of both Arab and African traditions, was

dominant in the population as a whole.

There is no doubt that the local Africans shared a large number of

attributes with the Arabs that they were now challenging. But precisely

because the challenge was against the Arabs, it made sense that its

chief articulator in the initial Stages should be distant enough to

symbolize the purity of the African challenge. The bonds in this case

were not the bonds of culture, or of religion, or even of

intermarriage. In many ways the majority of Zanzibar! Africans had more

in common with the majority of Zanzibar! Arabs than they had with this

Langi revolutionary from Uganda.

But what was at stake in that revolution was racial sovereignty rather

than national sovereignty. By the tenets of national sovereignty,

Sheikh Ali Muhsin, the leader of the Zanzibar Nationalist Party which

was overthrown, as well as the Sultan himself, were more Zanzibar! than

John Okello. But by the criterion of racial sovereignty it was the fact

that John Okello was an African in a purer sense than either Muhsin or

the Sultan which really mattered. A Langi on the Isle of Cloves was a

symbol of pure Africanity.

On 12th January 1964, the discontented Zanzibar civilians organised an

uprising headed by John Okello, a Ugandan of Langi origin who had

settled in Zanzibar in 1952 as a painter and stone worker and active

member of the Afro Shiraz Party (ASP).

The immediate and most significant action in this revolution took place

on the night of 11th-12th January 1964. Okello organized people to pick

all sorts of tools and got rid of the Arab dominated government. The

ex-service policemen joined the local people. They seized Ziwani and

Mutoni police stations from where they got firearms to control the

island completely.

On January 12, 1964 the people of Zanzibar woke up to hear a certain

Field Marshall John Okello raving over the radio: "I have an army equal

to a swarm of locusts. The power behind me is 999,999,000. Those who

oppose me will be cut into pieces, thrown into the ocean, be burnt, or

tied on trees for novice marksman to practice on. I want Mr. Harusi to

kill himself and his sons, or we will do it for him." Okello announced

that Zanzibar had been declared a republic and that Sheikh Abeid Karume

would be the president.

After taking control over the city, the supporters of ASP looted and

destroyed Arab and Asian shops and businesses. Arabs were forced out of

government. Sheikh Abeid Karume, leader of ASP became the president. He

was later assassinated in 1972. Field Marshall John Okello as he was

known among the supporters was later arrested and deported. He just

came back to Kampala to sell his story of the revolution to those who

wanted to listen.

National Movements and New States in Africa