The second Nigerian coup,July 1966

If the January coup is seen, in retrospect, as a southern or even a national coup rather than an Ibo affair, that is not how it came to be viewed in the North. The second coup, in July was to a large extent a revenge coup, directed against Ibo officers; though it was also an attempt by northern junior officers and NCOs to overthrow threatened southern political domination.

Major-General Aguiyi-Ironsi became Head of State by accident; he started to rule Nigeria without a policy or clear sense of direction; but he soon found his way; then tragically he lost it, and Nigeria began to fall apart.

The achievements of the six-month Ironsi regime tend to be obscured by the more obvious failures; but they were real nonetheless.

Peace was restored to the Western Region, as the western Military Governor, Lt-Colonel Fajuyi, jailed the NNDP politicians.

Economic planning was Stable and realistic; considerable development aid was received from Western countries and the AID bank; negotiations were concluded for Nigeria's association with the European Economic Community and a treaty was signed in July.

Ironsi was successful for some months in holding the balance between different regions in his appointments and he was conciliatory to the North in various ways.

Major Hassan Katsina the son of the Emir of Katsina was appointed Military Governor of the North. Lt-Colonel Gowon, a northerner from the plateau, was made Chief of Staff with virtual command of the army.

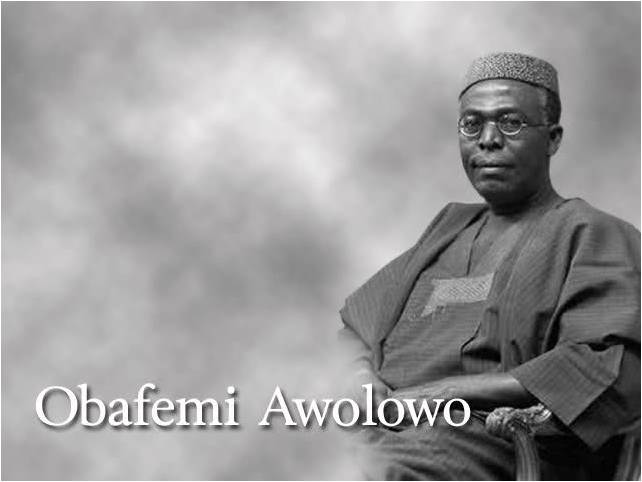

Ironsi delayed releasing Awolowo and his Action Group associates to allay fears that the South had conspired against the North in January. The date fixed for their release was overtaken by the second coup.

Ironsi also temporized over Tiv demands for a Middle Belt state to be carved out of the North.

But the initial promise of Ironsi's regime soon turned to general disillusionment and even to severe apprehensions in the North.

Ironsi became increasingly dependent on an inner clique of Ibo advisers whom he appointed as heads of crucial commissions, a development which quickly caused a flare-up of Yoruba-Ibo rivalry among civil servants and in the longer run caused a violent reaction in the North.

Ironsi accepted the proposals of Francis Nwokedi for radical reform of the public services and incorporated them in decree No. 34, on 24 May. The decree abolished the regions and unified the federal and regional public services. Nigeria was to be divided into 35 provinces. The decree marked the end of federalism and the beginning of unitary government.

Decree No. 33 issued at the same time banned political parties and ethnic societies and organizations for three years. Decree No. 33 met with little opposition but decree No. 34 seriously alarmed northerners who reared northern civil servants would be displaced by more educated southerners, it united all northerners including the Middle Belt communities who feared the domination in particular.

Five days after decree No. 34 was announced, a wave of fierce mob killings of Ibos broke out in northern towns and cities. The killings were starred off by a demonstration in Zaria of Students from the Institute of Public Administration, who feared for their future employment and carried slogans such as 'Avenge the Sardauna's death' and "Northern Unity'.

The slogans of the Zaria students indicate that factors other than fear of being swamped by Ibo civil servants had also alienated the North from Ironsi 's government. By May it had been realized in the North that Ibos were hardly touched in the January coup but the reasons for this were not understood.

It was widely believed in the North that the killings of politicians and army officers in January were ethnically selective, and that Ironsi had no intention of court-martialling Nzeogwu and his colleagues for the murders of Northern political leaders and senior army officers. In fact Ironsi had made a decision to court- martial them later in the year. But this, like the release of Awolowo, was overtaken by events (the second coup).

Ironsi's delay in punishing the coup majors the also had to mollify the South who wanted them released was a major error of Judgement and a major example of lack of leadership, for it was construed in the North as complicity in the murders of 15 January. The behaviour of many Ibos lent credence to those sorts of views in the North. Ibo traders, for example, put up pictures of Nzeogwu and Ironsi side by side in, their shops, boasted in public of the Ibo 'victory' in January, sang Ibo songs celebrating the overthrow of the Sardauna, and even played regularly an offensive gramophone record on the same subject.

Northern reaction to this kind of behaviour can be gauged from a typical editorial headline in the Hausa vernacular newspaper, the Gaskiya ta fi Kwabo of Kaduna; 'Discipline these Insolent Ibos Living in the North (28 March 1966). Ibo traders in the North were also bitterly unpopular as they had to bear the brunt of Hausa discontent at rising prices, especially of foodstuffs.

The northern mobs who engaged in the May killings adopted the cry Araba! ('Let us part') - so strong was their fear of southern domination. But-the northern soldiers were determined to defend northern interests by decisive action at the centre.

By May the northern Junior officers and other ranks were extremely hostile to the Ibo-dominated higher ranks. Apart from sharing the central grievances of the North, they were alarmed at the promotion of Ibos by the Aguiyi Ironsi government. Eighteen out of 21 new lieutenant- colonels were Ibos - an act carried through by Ironsi" against advice by the SMC, and Justifiable in terms of army seniority, but a major blunder in public relations.

Then in July the regular quota of northern recruits (50 per cent of the total) was rejected; it seems Ironsi planned to 'easternize' the infantry battalions so that they would be more likely to obey eastern officers.

Northern NCOs felt they were going to be purged. At this stage it would take only a small spark to explode the rinder-box of northern military discontent. A rumour had set off the January coup; the coup in July was ignited by another rumour: that Ibo officers were plotting to kill the remaining northern officers. The northern Junior officers and NCOs felt they had to pre-empt events.

The northern NCOs were very active in this second coup. The coup began on 29 July with the killing of Ibo officers in Abeokuta barracks, a process that was soon repeated in Ibadan, Ikeja and the North. Ironsi and the western Military Governor, Fajuyi, were arrested at State House, Ibadan, tortured and shot.

Like the first coup, the second was only partially successful and was aborted in the Mid-West and the East. Action was fore- stalled in Enugu by the eastern Commander of the First Battalion, Lt-Colonel Ogunewe. But the coup achieved its purpose: Ironsi was dead, and 43 officers and 171 other ranks of Ibo origin had been lulled.

What was Gowon's role in the coup? The intensely professional Chief of Staff originated from the minority Angas community of the northern plateau, and was a Christian from a predominantly Muslim region. He had no ethnic axe to grind. During the coup Gowon went to Ikeja to look at the trouble there. He was so shocked at the killings that he was placed under guard. However, Gowon soon ceased to be a prisoner, as the northern NCOs chose him to be their new Commander-in-Chief and Ironsi's successor as Head of State. The Middle Belt sergeants and corporals looked to Gowon as the best bet to avert the threat of secession from the North and domination by either Hausas, if they did not secede, or Ibos. The paradox of this way of thinking was that the second coup would prove to be the first stage in a series of events that would lead to secession by the Ibos of Eastern Nigeria.

The second Nigerian coup was clearly a coup of rivalry for power rather than of reform. In fact we might here bring in a distinction between a politically inspired military coup and a militarily inspired military coup.

A politically inspired military coup is one where issues of rivalry or reform are connected with wider issues of policy concerning the political system, and principles of government as they impinge upon relations between participants. An obvious example is the first Nigerian military coup, in January 1966.

A militarily inspired military coup, on the other hand, is concerned with questions of internal military organization or relations between those concerned with military policy and decision-making. A politically inspired military coup tends to include an ideological component even if the dominant motives are concerned with the rival or rivals for power.

A militarily inspired military coup is more likely to be concerned with issues of who makes military decisions on recruitment, strategy or deployment. The second Nigerian coup was vehemently militarily inspired.

Victims (july 29, 1966)

The then Head of State, Ironsi was assassinated in Ibadan with his host, Lt. Col. Adekunle Fajuyi, the governor of Western Region who would not give up his guest. Other officers of Igbo extraction suffered similar fate. They comprised Lt. Col. I.C. Okoro, Majors Dennis Okafor, Nzegwu, P.C. Obi, J.K. Obienu and lieutenants E.C.N. Achebe, Ekedingyo, Ugbe, S.A. Mbadiwe and A.D.C. Egbuna.

Equally sent to the great beyond were other officers in J.O.C. Ihedigbo, E.B. Orok, I. Ekanem, A.O. Olaniyan, B.Nnamani, A.R.O. Kasaba, F.P. Jasper, H.A. Iloputaife, S.E. Maduabum and J.I. Chukwueke. In addition to these 42 officers killed plus no less than a hundred non-commissioned officers who died, thousands of innocent civilians mostly of Eastern Nigeria origin lost their lives as a consequence of this coup.

Survivors

Yakubu Gowon, a 32-year-old lieutenant colonel then and Chief of Army Staff was to mount the throne. He was one main survivor and key beneficiary. Add to this list other Northern officers of the same rank in Murtala Muhammed and Theophilus Danjuma. As Major-Gen. David Ejoor, the Chief of Staff, Nigerian Army between 1972 -1975 was to react later; "the reaction of the Igbos to this coup culminated in the bloody civil war that lasted for about 30 months."

For nine years, Gowon pioneered the affairs of the country. During the days of the oil boom, he occasioned some developments even though there were whispers about corrupt enrichment by some of his officials.

Having accomplished the return of the political administration of Nigeria to the North, Gowon set out to restore the Nigerian federalism and created 12 states to decentralize and bring government nearer to the people.

Again, his administration had fashioned a democratisation process that was designed to enthrone civilian governance but when he played the midwife in aborting that dream, he had won more enemies, relentless critics and unyielding cynics.

National Movements and New States in Africa