Significance.

Significance of the Manchester Conference

Nigerian Leader Chief Obafemi awolowo attended the Conference

Nigerian Leader Chief Obafemi awolowo attended the Conference

It brought together blacks from Africa and those in the Diaspora. Nationalists who attended from Africa included Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, T.R. Makonnen of Ethiopia, Peter Abrahams of S. Africa, Wellace Johnson of Sierra Leone, Obafemi Awolowo of Nigeria, Hastings Kamuzu Banda of Malawi, Namdi Azikiwe of Nigeria etc. Those from the Diaspora included Dr. Peter Milliard, George Padmore and W. E. B Dubois.

The delegates adopted the use of force to obtain the independence of Africa. They observed that the gradualist methods of negotiations with colonial masters wouldn't lead to the desired independence.

It was agreed that Pan Africanism had to get a base within Africa. They realized the hopelessness of fighting colonialism using foreign bases-

Delegates called upon African elites overseas to return to Africa and champion the struggle against colonialism. Hence the return of Nkrumah to Ghana in 1947 and Namdi Azikiwe to Nigeria in 1960.

The educated were sensitised on the need to identify themselves with their uneducated brothers and sisters. They were called upon to stop minimizing the illiterate but instead mobilize them and enlighten them about the need for independence. The educated were also argued to stop serving the interests of colonial masters.

It led to the introduction of Pan Africanism on the entire continent of Africa. On returning to Ghana in 1947, Nkrumah spearheaded the struggle for the independence of Ghana and later freedom for all African peoples. He made several travels within and outside Ghana and wherever he went, he spread Pan African ideas.

The idea of the future union of Africa was forwarded and participants were asked to give it serious thinking. This later led to the formation of the Organization of African Unity (O.A.U) in 1963.

During the Manchester conference, the elites were challenged to return to Africa and form political parties and liberation movements so as to fight for African independence.

It bridged the

various differences amongst African nationalists. Nationalists of the old

generation like Jomo Kenyatta were united with young nationalists like Kwame

Nkrumah. Nationalists of the Casablanca group sat on the same negotiating table

with those of the Monrovia group. Participants were also warned about the

dangers of aligning with super powers. Nationalists from French colonies e.g

Leopold Sedar Senghor sat on the same table with nationalists from British

colonies e.g. Namdi Azikiwe of Nigeria.

It bridged the

various differences amongst African nationalists. Nationalists of the old

generation like Jomo Kenyatta were united with young nationalists like Kwame

Nkrumah. Nationalists of the Casablanca group sat on the same negotiating table

with those of the Monrovia group. Participants were also warned about the

dangers of aligning with super powers. Nationalists from French colonies e.g

Leopold Sedar Senghor sat on the same table with nationalists from British

colonies e.g. Namdi Azikiwe of Nigeria.

The principle of self-sacrifice was emphasized. Participants were argued to give in their time, ability, finances and life in order to emancipate the continent from colonialism.

Richer African countries and individuals as well as the rich blacks in the Diaspora were called upon to give financial support to Africans struggling for independence.

The Manchester conference was followed by 12 years without any Pan African meeting.

Within that period, nationalists who had attended the Manchester conference were busy organizing for the independence of their countries. In preparing for independence, they made use of the ideas and strategies, which had been propounded during the Manchester conference. During the 12-year period, pan African ideas never eclipsed. Various books, newspapers and nationalistic speeches continued articulating the Pan African philosophy, e.g. In 1955, George Padmore published his famous book " Pan Africanism and communism." This soon became a handbook for African nationalists.

After 1945 there was an apparent lull in pan-Africanism, in the sense that no pan African conferences were held until 1958, when Nkrumah organized the All African People's Conference in Accra, and that during this period African nationalist leaders concentrated on the struggle for individual African territories and ignored pan-African federalism. Yet the struggle for independence in separate states was not inconsistent with pan-Africanism but was essential to it. It was merely the first stage in Garvey's plan for an all-African Union, the essential preliminary and groundwork for the second stage: the unification of independent African states.

An ominous feature of the 1945 Congress was the almost complete absence of French African participation. This happened partly because of language difficulties, but mainly because the French African nationalists were, at this time, heavily communist. Even Felix Houphouet-Boigny, later president of the pro-West and free enterprise Ivory Coast, was a communist in 1945. And being communist, they were pan-working-class rather than pan-African. They were also very heavily involved in French working-class politics, and were attached to French parliamentary institutions and the evolue philosophy. They wanted to achieve French citizenship for Africans, rather than independence.

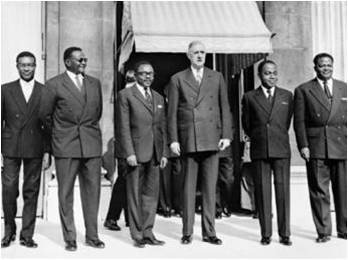

Presidents Felix Houphouet-Boigny and Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana to Abidjan in 1957

The ideological difference and organizational separation between French-speaking and English-speaking African leaders was to continue throughout the post-war period, and into the independence era, and it persists today. This separation is a tragedy because it was French-speaking black intellectuals who, in the 1930s, founded the 'negritude' movement to assert a black man's cultural values against the onslaught of European cultural tyranny. One of the leaders of this movement was the Martinique poet Aime Cesaire, famous for the lines:

Hurrah! for those who never invented anything!

Hurrah.' for those who never conquered anybody!

It was Cesaire who coined the word 'negritude', which means 'assertion of black culture'. But it was the Senegalese, Leopold Sedar Senghor, who came forward as the leading defender of African culture and the most powerful proponent of a Universal Civilization in which Africa achievement played an integral role. The 1930s and 1940s saw a blossoming of black poetry in the French language, poetry of high literary quality and of deep political commitment. In the words of one of" black Africa's greatest historians, Joseph Ki-Zerbo of Upper Volta: 'To the war drum of Cesaire, responded the lyre of Senghor, the trumpet of David Diop, the flute of Dadie and of Birago Diop, the Caribbean cymbals of Tivolien, Paul Niger, Paul Remain and Leon Damas, and the Malagasy horn of Rabemananjara.' English-speaking Africa has, so far, been much slower than French-speaking Africa in reasserting African cultural values. Perhaps it needs the inspiration of the French-speaking black poets of the last generation.

National Movements and New States in Africa