Introduction

The French occupation of Algeria began with the conquest of the Turkish-ruled city of Algiers in 1830 and was completed when General Bugeaud finally overcame the lengthy, determined resistance of the nationalist leader Abd El Kader in 1847. From the beginning France settled large numbers of poor whites from France itself, from Spain and from Malta in Algeria.

By the time of the Second World War there were approximately one million European settlers or colons in Algeria. There were eight times as many Muslims, but Algeria was ruled as part of metropolitan France, with direct representation in the National Assembly in Paris, though with only 13 seats - a disproportionately low number.

The war ended the isolation of French-ruled Arabic-speaking North Africa from the ideas of the outside world. Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia experienced an invasion of American troops and American ideas of self-governing anti-colonialism, an emergency wartime industrialization which created a new urban proletariat, the spectacle of French disunity as the Vichy French and the Free French waged real war against each other, and excitement at the ending of the French colonial Mandates over Arabic-speaking Syria and Lebanon.

The war saw the emergence of Ferhat Abbas as the most dynamic representative of a burgeoning Algerian nationalism. Abbas, born in 1899; was the grandson of a prominent Muslim land owner dispossessed by the conquest Abbas' father raised him as a European and the boy spoke French as his first language, but the discrimination Abbas experienced as a conscript in the French army soon cured him of any respect for colonialism. At Algiers University he became president of the Algerian Muslim Students Association and was attracted by the democratic principles and the concern for human rights of great French writers like Michelet and Victor Hugo and the socialist Jean Jaures.

At the same time Abbas steeped himself in Islamic history and came to believe in. the value of an Algerian State combining the best in the French and Islamic political 'and cultural traditions. On 10 February 1943 Abbas and 55 other Muslims signed the Manifeste du Peuple Algerien. The Manifesto was a moderate document. It called for an Algerian constitution guaranteeing liberty and equality of all inhabitants without distinction of race or religion and recognition of Arabic as an official language alongside French. A supplement to the Manifesto, issued shortly afterwards, called for an 'Algerian state A few months later General de Gaulle's Free French took over administrative control of Algeria. Abbas was arrested and exiled to a remote village? However from there he managed to contact another prominent nationalist: ex-serviceman, ex-communist and ex- factory worker Messali Hadj, and together they managed to form, in the town of Setif, the Amis du Manifeste De Liberte (Friends of the Manifesto of Liberty). It was at Setif that the first act in the armed Struggle for Algerian independence was played.

On 8 May 1945, VE Day (a day to celebrate Victory in Europe over the Germans), the Setif Muslims who supported Messali turned the celebration into a nationalist demonstration) Alongside Allied flags they carried banners reading 'Down with colonialism" and 'Long live a free Algeria'. Police tried to seize the banners, scuffles broke out, a panic- stricken policeman started shooting, and a full-scale battle began. On that day and the next three days Muslims attacked Europeans, mainly officials, and killed about a hundred of them in Setif, the Constantine area and the mountains of Kabylia.

The response of the French government and armed forces and the colons to these massacres was indistinguishable from what the German Nazis had, up to a few months earlier, been doing at will in areas of resistance in Europe. Retaliation was planned and deliberate. French troops, fighter planes and bombers aided by gangs of colon vigilantes attacked and wiped out whole villages, killing thousands of Muslims, men, women and children alike. Fairly reliable estimates put the number of dead at 18 000 to 20 000. The main effect of the Setif rising and its brutal suppression was to destroy the faith of most moderate, French-educated Muslim leaders in a progressive non-violent and constitutional evolution towards self-government. After May 1945 they began to think in terms of an armed uprising, properly organized and nor spontaneous as at Setif.

The French response to Setif, in the aftermath of the counter-massacre, was to attempt to apply a dose of mild political reform in Algeria. In the June 1946 elections to the 13 Algerian seats in the French Constituent Assembly, Abbas was allowed to put up candidates of his newly formed Union Democratique du Manifesto Algerien (UDMA), which won 71 per cent of the vote. The new French constitution of September 1947 increased Algerian representation in Paris to 18 in the Union Assembly and in the National Assembly; to 30 in the Chamber of Deputies; and to 14 in the Senate. Half of the National Assembly Algerian seats were reserved for Muslims. Algeria itself was given a two-college Assembly for local matters; an all-Muslim college and a mixed Muslim-European college. The first college came to be dominated by collaborationist Muslims and the second by colons, in both cases because the elections were 'arranged' by the administration. Whatever faith some Algerian Muslims still had in the democratic process as a vehicle of change was irretrievably destroyed. Already some of the younger nationalists had turned to the armed struggle.

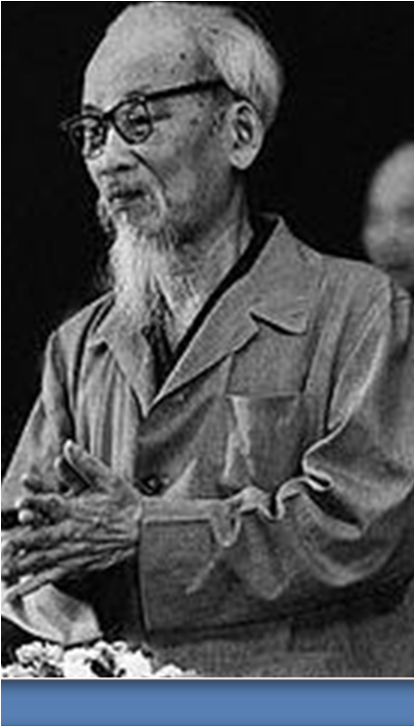

Comrade

Ho chi Minh organized the Vietmin rebels who defeated the French at Bien Dien

Phu. The success inspired many Africans to resist colonialism.

Comrade

Ho chi Minh organized the Vietmin rebels who defeated the French at Bien Dien

Phu. The success inspired many Africans to resist colonialism.

In 1947 younger radicals in Messali's party formed the Organisation Secrete (OS), an underground movement, and began collecting funds and arms for an insurrection. Prominent among them was Ahmed Ben Bella, born in 1919, a merchant's son from the Moroccan border town of Marnia, and a former French army sergeant in Italy and Indo- China. Later they were joined by Belkacem Krim, another ex-serviceman, who had been organizing a similar secret guerilla nucleus among his Kabyle people in the mountains. Many of the OS leaders were arrested by the police early in 1950.

In March 1952 Ben Bella escaped from Blida jail and made his way to Cairo, where he joined Krim and Others. Actively encouraged by the new Egyptian government of Nasser, the OS survivors formed, in March 1954, the Comite Revolutionnaire pour 1'Unite et 1' Action (CRUA), the forerunner of the Front de Liberation Nationale (FLN).

CRUA was an exile-based movement but was determined to fight for independence within rather then outside Algeria. It was composed of representatives of all regions of Algeria and from the beginning assumed a national approach to the struggle. Surprisingly, the CRUA, while planning an armed rebellion, did not believe in an ultimate military victory over French forces; its leaders felt certain that violence in Algeria would provoke France into granting an independent Algerian state under majority rule. So it proved;, but they had not envisaged that the war would take eight long years and that nearly a million would die before political independence was achieved.

The Algerian War of Independence broke out on 1 November 1954, as the FLN struck in 70 different places all over the country, but predominantly in the Aures Mts area of the east. Attacks were made on French administrative posts, police stations, army camps, railway lines and bridges. The FLN made it clear, through their tracts and secret proclamations, that they were acting in a long tradition of Algerian nationalism and were concerned not to take over a colonial state, but to restore a formerly independent one. This was well expressed by Frantz Fanon, the Martinican psychiatrist and political philosopher who resigned a senior medical appointment in Algeria to join the rebels:

It is true that the FLN is constantly being reproached for this constant reference to the Algerian nation before Bugeaud. That is because by insisting on this national reality, by making of the Revolution of 1 November 1954 a phase of the popular resistance began with Abd El Kader, we rob French colonialism of its legitimacy, its would-be incorporation into Algerian reality. Instead of integrating colonialism, conceived as the birth of a new world, in Algerian history, we have made of it an unhappy, execrable accident, the only meaning of which was to have inexcusably retarded the coherent evolution of the Algerian society and nation.4

As the months went by the rebellion spread, from the Aures Mts westwards to Kabylia. The new Governor-General, Jacques Soustelle, arrived in January 1955. Soustelle followed a twin policy of keeping Algeria French and carrying out administrative and economic reforms in hopes, of satisfying Muslim discontent. In his first policy speech Soustelle announced;

France is at home here, or rather, Algeria and all her inhabitants form an integral part of France, one and indivisible. All must know, here and elsewhere, that France will not leave Algeria any more than she will leave Provence and Brittany. Whatever happens, the destiny of Algeria is French.5

Thus Algeria was an integral part of France. Yet alongside strict security measures. Soustelle tried to reform the administration, by decentralizing much of its work, allowing Muslims a greater role in local government and by establishing a new corps of European officials known as the Sections Administratives Specialisees (SAS).

The SAS officers were army lieutenants or captains appointed as district officers to administer directly the areas under their control. Their duties originally were to develop education, to improve agricultural methods, to supervise health and house-building programmes and to act as a Judiciary. However Soustelle's SAS failed to undercut Algerian nationalism.

In the first place, the officers were thrown into their jobs at the deep end, too hastily, with no time to learn Arabic.

Secondly, due to the shortage of officers and men in the security forces in Algeria the SAS men were often forced to act as policemen and soldiers; thus the Muslims lost confidence in them.

Thirdly, there can be little doubt that French reforms of the type launched by Soustelle were more than offset by the destruction of homes, villages and agricultural land by the French army in the war against the FLN.

Fourthly, by the mid-1950s it was far too late for the French to deflect the course of Algerian nationalism by attemptingtofight poverty and solve the housing problem.

The failure of French attempts at reform after the rebellion had begun was emphasized by the fact that many of the moderates who initially rejected the rebellion later decided to join it. Ferhat Abbas, for example, condemned the use of force even after 1 November 1954. as did Messali Hadj.

Ahmed Ben Bella, Revolutionary leader of Algeria

Ahmed Ben Bella, Revolutionary leader of Algeria

Even the Algerian Communist Party condemned the rebellion, out of anxietytomaintain its links with the French Communist Party. The Algerian CP remained equivocal in its attitude to the rebellion and changed its line no faster than did later French governments. Messali's supporters were frequently driven towards the FLN when so many of them were arrested on false charges of aiding the FLN; as in Kenya in 1952', at the outbreak of the rebellion the colonial administration was unable to distinguish between the armed militants and the non-violent moderates in the nationalist ranks.

Abbas moved away from his initial stance to an espousal of the FLN cause in January 1956 for a number of reasons- The main reason was his failure to secure political reforms through constitutional means in the previous two years in particular. In an interview Abbas said: 'My role, today, is to Stand aside for the chiefs of the armed resistance. The methods that I have upheld for the last fifteen years - cooperation, discussion, persuasion - have shown themselves to be ineffective; this I recognize .

It is significant that Abbas moved with the bulk of Algerian public opinion towards belated support for the FLN. The second reason for his throwing in his lot with the FLN was his shock and disgust at French counter-revolutionary reprisals, carried to excess and far exceeding in ferocity the acts of revolutionary violence which provoked them. From January 1956 Abbas' role in the FLN was twofold: from his base in neutral Switzerland close to the French border he was the prominent publicity agent of the FLN in western Europe; he was able to persuade the governments of Morocco and Tunisia, which both gained independence in 1956, to give their open support to the cause of Algerian freedom.

The French government of the liberal-minded Prime Minister Pierre Mendes-France had moved Morocco and Tunisia towards independence in progressive stages in 1954 and 1955. partly in order to avoid full-scale armed risings on either side of Algeria. The appointment in January 1956 as French Prime Minister of Guy Mollet, a socialize who had attacked Soustelle's integration policy and had advocated direct negotiations with the FLN. raised the hopes of Algerian nationalists, armed rebels and moderate reformers alike, that a political solution and an end to the war were in sight. Mollet, however, abjectly surrendered to pressure from the colons, who held massive anti-nationalist demonstrations in the streets of Algiers. The new premier cancelled the appointment of the liberal Catroux as Soustelle's successor as Governor-General, and on 9 February 1956 Mollet said in a broadcast made especially for the Europeans of Algeria: 'France will remain present in Algeria. The bonds linking metropolitan France to Algeria are indissoluble.'7

Mollet's weakness convinced many remaining Algerian waverers that only successful aimed struggle would influence Paris governments; it also encouraged extremists in the French army who helped to overthrow the Fourth Republic two years later.

Mollet did summon up enough courage later in the year to begin secret negotiations with the FLN, in October. However the talks were wrecked by a deliberate act of provocation on the part of the French air force and army. Ben Bella, the FLN leader, was kidnapped on a flight across Algeria from MoroccotoTunisia, when the pilot of the plane in which he was a passenger was ordered to land at Algiers. However, it is doubtful anyway if the talks, had they continued, would have achieved anything; it seems that the most Mollet would have been prepared to concede at this time internal self-government for Algeria felt far short of the FLN's minimum demands.

The year 1956 marked a crucial turning point in the development of the FLN as a guerilla movement and a political organization inside Algeria. Until 1956 the FLN had won several successes. It had proved itself generally more mobile than the heavily- equipped French army. The counter-revolutionary warfare of the French-including mass arrests of suspects, destruction of entire villages in collective punishments, and brutal interrogation - had helped to turn the mass of the population towards the FLN. However, in purely military terms the rebels had made little impact, In early 1956 the wilaya (district) commanders of the FLN were engaged in Strong rivalry with each other and there was little co-ordination amongst them. Events throughout the year conspired to transform the FLN into a more disciplined and mass-based movement.

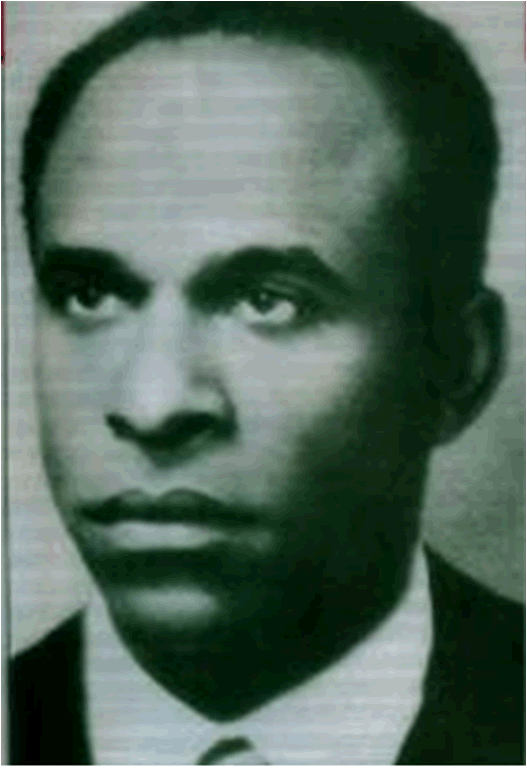

FRANTZ

FANON's ideas contributed to the growth of a spirit of nationalism that

sustained the war.

FRANTZ

FANON's ideas contributed to the growth of a spirit of nationalism that

sustained the war.

In January Abbas announced his conversion to armed revolution. In February Mollet surrendered to a colon counter-revolution. In March, Morocco and Tunisia gained independence. Even more important, later in March two Algerians, Ferradj and Zabanala, were executed for bearing arms against France. In April a European counter-terrorist group bombed a block of flats in the Kasbah, the Muslim quarter of Algiers, killing 53 people. In August the guerillas held a conference of leaders of their various factions in the Soumman Valley.

A form of parliament was set up, and matters of strategy, tactics and organization were discussed. The results of the Soumman Conference were: the creation of the ALN (Army of National Liberation) to link up all the 20 000 guerillas, with each unit being given a precise sector to operate in; and a substantial boost in morale for having been able to hold the conference inside the country. By the end of 1956 the FLN organization had moved into the towns in strength, in the form of urban terrorism. The 'battle of Algiers', where the FLN used the Kasbah as an urban guerilla base, lasted for a full year after October 1956. The General Union of Algerian Workers organized support for the FLN in the city.

Eventually Genera Massu's paratroops managed to win the battle in Algiers by mass arrests and brutal torture of civilians. The campaign in Algiers failed in itself, but it could be argued it succeeded as a diversionary attack, for the French paid less attention to the countryside, and late 1956 and early 1957 was the period when the FLN actually gained physical control of scattered pockets of Algerian territory. At this time there were large- scale desertions in Muslim units in the French army, successful ambushes of French columns and widespread sabotage of agriculture and communications. November 1956 saw the withdrawal of the Anglo-French invasion forces from the Suez Canal. President Nasser of Egypt sent large consignments of abandoned British military equipment, mainly Lee-Enfield rifles and ammunition, to the FLN through Tunisia, In addition the FLN bought arms from elsewhere with funds from other Arab League countries, and used much stolen and captured French equipment.

From 1956, some rural communities were in effect liberated areas under the control of the FLN, who administered through tax collectors, political commissars and judges. Such opportunities in self-government, on however small a scale, helped to remodel the consciousness of the Algerians involved. In Fanon's words again:

The Algerian combatant is not only up in arms against the torturing parachutists. Most of the time he has to face problems of building, of organising, of inventing the new society that must come into being. That is why colonialism has lost, has irreversibly lost, the battle in Algeria. In every wilaya, cadastral plans are drawn up, school building plans studied, economic reconversions pursued.

Fanon's writings have revealed to us the crucial role played by women in the Algerian revolution and the dramatic changes in the social role of women as a result of the war. The veil was seen by Algerian women both as a badge of identity and as a basis of solidarity. It came to be also an instrument of revolution. The French resorted at times to Ac personal aggression of forceful unveiling of women in the streets.

The situation got worse when Algerian women became more systematically committed to revolution. They were publicly unveiled partly out of the French soldiers' desire to subject them to indignity, but also at times out of suspicion that behind the veil was a Sten gun. This was in fact the time when the Algerian women converted the veil more fully into a military camouflage. A technique was evolved of carrying a rather heavy object dangerous to handle inside the veil, and still give the impression of having one's hands free, of there being nothing under this hiak except a poor woman or an insignificant young girl. It was not enough to be veiled. One had to look so much like fatma that the soldier would be convinced that the woman was quite harmless. Fanon goes on to say that this technique was in fact extremely difficult.

Three metres ahead of you the police challenge a veiled woman who does not look particularly suspect. From the anguished expression of" the unit leader you have guessed that she is carrying a bomb or a sack of grenades, bound to her body by a whole system of strings and straps. For the hands must be free, exhibited bare, humbly and abjectly presented to the soldiers so that they will look no further-''

But with the conversion of the veil into a military camouflage the enemy gradually became extra alerted:

In the Streets one witnessed what became a commonplace spectacle of Algerian women glued to the wall, over whose bodies the famous magnetic detectors, the 'frying pans', would be passed. Every veiled woman, every Algerian woman, would be suspect. There was no discrimination. This was the period during which men, women, children, the whole Algerian people, experienced at one and the same time their national vocation and the recasting of the new Algerian society. But Ac Algerian woman sometimes abandoned the veil as an exercise in military camouflage. There were occasions when it was important that the feminine Algerian soldier should walk the streets looking as Europeanized as possible. For some of these girls it took a lot to escape the sense of awkwardness which came with walking in the street unveiled. But the old fear of dishonour was swept away by bold feelings of commitment to a national cause.

Fanon has also indicated more clearly than any other writer the role of the radio as an instrument of resistance and revolution. From the beginning of the war the Algerian people had been able to listen to Cairo Radio, But in general they shunned the radio as a vehicle of French propaganda. Then from the end of 1956 the radio set became a prized object and a necessity for almost every Algerian family: they could now tune in to the Voice of Free Algeria. As Fanon put it, 'The radio was no longer a part of the occupier's arsenal of cultural oppression." More than that, the radio served to unite all Algerians, whether Arabic- or Kabyle-speaking, behind a common cause. The radio was now crucial in the remodeling of the consciousness of Algerians. 'It was the radio that enabled the Voice to take root in the villages and on the hills. Having a radio seriously meant going to war.11' As in the Second World War the radio had encouraged the French Resistance against the German occupation, so in the Algerian War the radio inspired the Muslim population to resist French occupation.

French military reaction to the expansion of FLN activities in the countryside was a programme of forcible regrouping of villages (1957-9) along the lines of British counter- revolutionary warfare in central Kenya, in a vain attempt to cut off contact with and support for the guerillas. In the same period atrocities were carried out by government forces disguised as ALN soldiers: a counter-productive measure which did a great deal to harden support for the FLN. (The white-settler regime in Zimbabwe used the Selous Scouts in a similar way with similar results - sec below.)

The French military retaliation against the FLN resulted in an act of colossal stupidity as well as brutality in February 1958, when French planes bombed an apparent FLN column in the Tunisian border village of Sakhiet Sidi Youssef, killing 68 people, all of them Tunisian villagers. This outrage led to international condemnation of French actions in Algeria in general, and even to diplomatic pressure from the United States (which did not wish to sec too many French NATO troops tied down in Africa), As a result the French government tentatively prepared for negotiations with the FLN. This was too much for the colons and the French army in Algeria, which rose up in revolt and overthrew the French Fourth Republic.

On 13 May 1958 a colon mob seized government buildings in Algiers, while French paratroops looked on approvingly. The French government of Gaillard was being replaced by one under Pflimlin but control was passing out of the hands of the Paris politicians. On 1 June 1958 General Charles de Gaulle, after twelve years in the political wilderness, was sworn in as Prime Minister in Paris. Later in the year De Gaulle became President of the Fifth Republic, with a new constitution providing for a long executive presidency.

De

Gaulle came to power because the politicians of the Fourth Republic lacked the

will to impose their authority on the French army in Algeria and the colons.

The soldiers and the colons enthusiastically backed de Gaulle, whom they saw as

a strong conservative military leader who would win the war for them in Algeria

and keep Algeria French. The army embraced De Gaulle as the strong leader who

would prevent another humiliation like the defeat of Dien Bien Phu in Vietnam,

which led to French withdrawal from all of Lido-China Just a few months before

the Algerian War began.

De

Gaulle came to power because the politicians of the Fourth Republic lacked the

will to impose their authority on the French army in Algeria and the colons.

The soldiers and the colons enthusiastically backed de Gaulle, whom they saw as

a strong conservative military leader who would win the war for them in Algeria

and keep Algeria French. The army embraced De Gaulle as the strong leader who

would prevent another humiliation like the defeat of Dien Bien Phu in Vietnam,

which led to French withdrawal from all of Lido-China Just a few months before

the Algerian War began.

Determination to regain the lost honour of the French army had been a powerful factor in the stubbornness and obstinacy of the soldiers in Algeria since November 1954. Indeed the very success of the Vietnamese against the French was for a while an obstacle in the way of the FLN in Algeria. The French officers in 1958 could not have imagined that the assumption of power by De Gaulle would in fact become the first major case of a metropolitan coup leading to colonial liberation in Africa. The second case was to be the Portuguese coup in April 1974.

In his first year in power de Gaulle showed no signs of changing the outlook of French policy in Algeria. He appeared to wish to retain Algeria as a province of France. De Gaulle's Algerian policy was at first essentially reformist. Muslims were given voting rights as French citizens in a referendum on the constitution of the Fifth Republic. In October 1958 de Gaulle launched the Constantine Plan which provided for rapid expansion of education, medicine and industrialization and rapid introduction of Muslims into public service.

In response to de Gaulle's reformist policy, in September 1958 the FLN set up a Provincial Government of the Algerian Republic (GPRA) in exile in Tunis. Ferhat Abbas was elected President of the GPRA. Late in 1959, however, de Gaulle either came to accept reality - that a minority European community, however powerful, could not in the long run prevail against a non-European majority - or he had accepted this privately for some time but now felt his position was strong enough for him t0 declare himself. In any case, he grasped the nettle of the Algerian problem and began positive moves towards a political solution based on majority rule. As a pragmatist de Gaulle was not averse to political reform in Africa - witness Brazzaville in 1944, the creation of the French Community in 1958 and the full independence of most French African territories in I960.

As a pragmatist and a ruler determined to restore France as a Great Power, De Gaulle was more concerned with the strategic implications of the tying down of half-a-million French troops in Algeria than with safeguarding the material interests of the colons. 0n 16 September 1959 the President of France made his first move on the path towards Algerian independence- He suggested a referendum on self-determination for Algeria.

This provoked a rising in January I960 by the colons who, aided by paratroops, erected barricades in Algiers. The rising was defeated by elements of the army loyal to De Gaulle and by the total non-cooperation of the Muslims with the colons. The failure of the colons' insurrection strengthened De Gaulle's position in negotiations with the GPRA; he had demonstrated he could exercise his authority over the army and the colons and could thus enforce whatever was agreed in negotiations.

In June I960 de Gaulle's government began direct negotiations with the GPRA (represented by Abbas) at Melun near Paris, These were soon deadlocked because France wanted a ceasefire before agreeing to political concessions. The winter of 1960-1 saw growing resistance by the colons. In 1961 elements of the colons, aided by sections of the army, formed the Organisation de 1' Armee Secrete (OAS) a terrorist group pledged to wreck any Paris-GPRA agreement, to assassinate de Gaulle and to carry out attacks on Muslims. On 22 April 1961 four generals in Algeria - Challe, Zeller, Jouhaud and Salan - aided by some regular troops, paratroopers and the Foreign Legion - revolted against De Gaulle and seized Algiers.

The revolt of the generals failed because the French conscript soldiers in Algeria remained loyal to de Gaulle and refused to obey the orders of rebel officers, and in France the great mass of the population, the army and the trade unions were also loyal to de Gaulle- In spite of continued OAS terrorism, negotiations for a political settlement went ahead, at Evian on Lake Geneva. In February 1962 De Gaulle admitted in a broadcast that Algeria would become independent.

On 18 March 1962 a ceasefire agreement was signed at Evian between French representatives and Belkacem Krim for the GPRA. Krim had replaced Abbas as chief negotiator after Melun because he was more representative than Abbas of the more radical socialist and neutralist orientation of the GPRA.

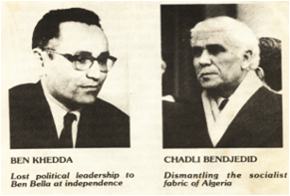

In a referendum m July 1962 as many as 99.7 per cent voted in favour of independence. Independence elections were held in September, but in the interim period two major developments had occurred: most of the colons left Algeria for France, and a military struggle for power between rival FLN elements had been fought out, Ben Bella, supported by most of the ALN led by its commander Houari Boumedienne, had emerged victorious.

National Movements and New States in Africa